Tyler Fleming

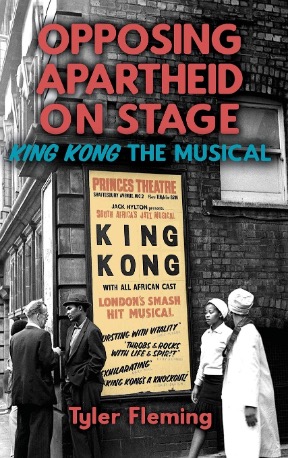

Opposing Apartheid on Stage: King Kong the Musical

University of Rochester Press, 2020

272 pages

$125 (hardcover), $24.99 (Ebook)

Reviewed by Neville Hoad, PhD

In seven riveting chapters, Tyler Fleming, associate professor of Pan-African studies and History at the University of Louisville, tells and retells the story of King Kong—the definitive South African musical of the twentieth century. King Kong was first performed in Johannesburg in 1959, a decade or so after the emergence of apartheid as the governing regime of South Africa. With its all-Black cast, tacit and occasionally overt government support, and significant commercial success and critical acclaim, it is an unlikely artifact of its time: a product of the apartheid era that also seems to resist the prevailing racial orthodoxies of that long and shameful period.

The title of the book—Opposing Apartheid on Stage—would initially appear to suggest that the author favors the resistant or oppositional register of both the content and the production history of the musical, but Fleming’s narrative and analysis quickly and continually establish a significantly more nuanced and ambivalent take. “With its African cast, orchestra, composer and storyline, King Kong was indeed all African, but it was also integrated in that its directors, producers, creators and organizers were almost exclusively white. King Kong was the result of herculean interracial collaboration on a scale that South African show business had never before witnessed.” Fleming notes that “With these interracial dimensions, King Kong challenged apartheid social conventions,” and indeed, the police threatened to charge everyone at the opening night after party with contravening the notorious Immorality Act, which prohibited interracial sexual relations inter alia. However, he goes on to recognize that nonetheless, the musical “arguably replicated the system’s racialized division of labor.”

To underscore this racialized division of labor, Fleming quotes the following extraordinary passage from Todd Matshikiza’s (the composer of the score of King Kong) 1961 memoir Chocolates for my Wife:

That time onwards began the most arduous time of my life. Every night I dreamed I was surrounded by pale-skinned, blue-veined people who changed at random from humans to gargoyles. I dreamed that I lay at the bottom of a bottomless pit. They stood above me, all around, with long sharpened steel straws that they out to your head and the brain matter seeped up the straws like lemonade up a playful child’s picnic straw . . . I dreamed that Black names were entered from the bottom of the register and White names from the top. And when a black man told a white man to go to hell, there was no hell. And when a white man told a black man to go to hell, the black man did go to hell.

Matshikiza’s recollection of his dreams while making King Kong render the production of the musical much more like a symptom of apartheid than an anomaly, but nevertheless the musical galvanized, and in some cases launched, the international careers of some of the most important Black South African performing artists of the twentieth century, including Hugh Masekela and Miriam Makeba. Fleming argues that this dialectic between exploiting and enabling Black excellence under distinctly racist political conditions is a key feature of the production and reception of King Kong. That dialectic is a familiar Black Atlantic one and throughout the book, the author scrupulously connects South African cultural production and history to the Black Atlantic. For example, Fleming goes beyond the truism that African American forms like jazz were profoundly influential on Black South African music in the period to suggest specifically the ways that films like Porgy and Bess and, particularly, Carmen Jones shaped the form of King Kong.

Opposing Apartheid on the Stage: King Kong—the Musical is a big and occasionally unwieldy book, and the dramatis personae is massive. Fortunately, Fleming demonstrates a deep familiarity with a long time span of history across multiple national contexts and their intersections. Chapter 1 introduces readers to the brief and tragic life of Ezekiel “King Kong” Dlamini—the legendary heavyweight boxer whose mythic story provides the ruse for bringing Black urbanity to the stage. Chapter 2 offers a lucid and poignant history of the Union of South Artists (USAA), the organization that produced King Kong and how over the course of its history it is more successful in moving Black artists into leadership positions than occurred in the production of the musical itself. Chapter 3 tracks the popular reception of the musical in South Africa, again paying careful attention to that reception’s complicity with and resistance to apartheid ideology, policies, and institutions, along the way revealing the contours of cultural agency on the terrain of politics. Chapter 4 reveals how King Kong’s 1961 tour failed to reproduce its South African successes due to differing national expectations around professionalism and African identity—too urban, not ‘tribal’ enough—and how the configuration of British racism confounded the careers of the performers who chose to stay in exile in Britain rather than return to South Africa. Chapter 6 follows the more successful careers of the cast members of King Kong who made it to and in the United States and their collaborations with each other and African and African American musicians already there. The final chapter revisits the short-lived and by most accounts disastrous 1979 revival of King Kong. While it would be impossible to cover fully the biographies of all the extraordinary people whose lives flash across these pages, the author does not flinch from facing the joys, triumphs, disasters, and suffering of the many South Africans who made and were made or unmade by their experiences with the musical.

If I have a question for this book, it would be: why King Kong now? Nostalgia for places like Sophiatown in Johannesburg or District 6 in Cape Town—vibrant, multi-racial places literally demolished by apartheid and powerfully brought into cultural prominence by phenomena like King Kong—has been an important part of post-apartheid attempts to find a useable past. I struggle to imagine any cultural work now, let alone a musical, that could have the impact and legacy of King Kong. Yet many of the issues raised by Opposing Apartheid on Stage are very much alive now: intellectual property and cultural patrimony, provisioning for artists and the future of cultural work, state support for the arts, how music is capitalized in an era of streaming platforms, and so on. The controversy around Paul Simon’s Graceland album, as well as the current legal battle over rights and royalties between Miriam Makeba’s grandchildren and the Makeba trust, and the strange role of the Arts and Culture minister in that dispute, are exemplary of this domain. Global and national arts and culture were indisputably important in the fight against apartheid, and King Kong and the subsequent careers of many of its cast members were a major part of that. What role might arts and culture play in a South African national polity defined by overwhelming un- and underemployment, rising inequality, and state capture, and what lessons, if any, might the stories of King Kong hold for South Africa in the world today?