Marcos Gonsalez

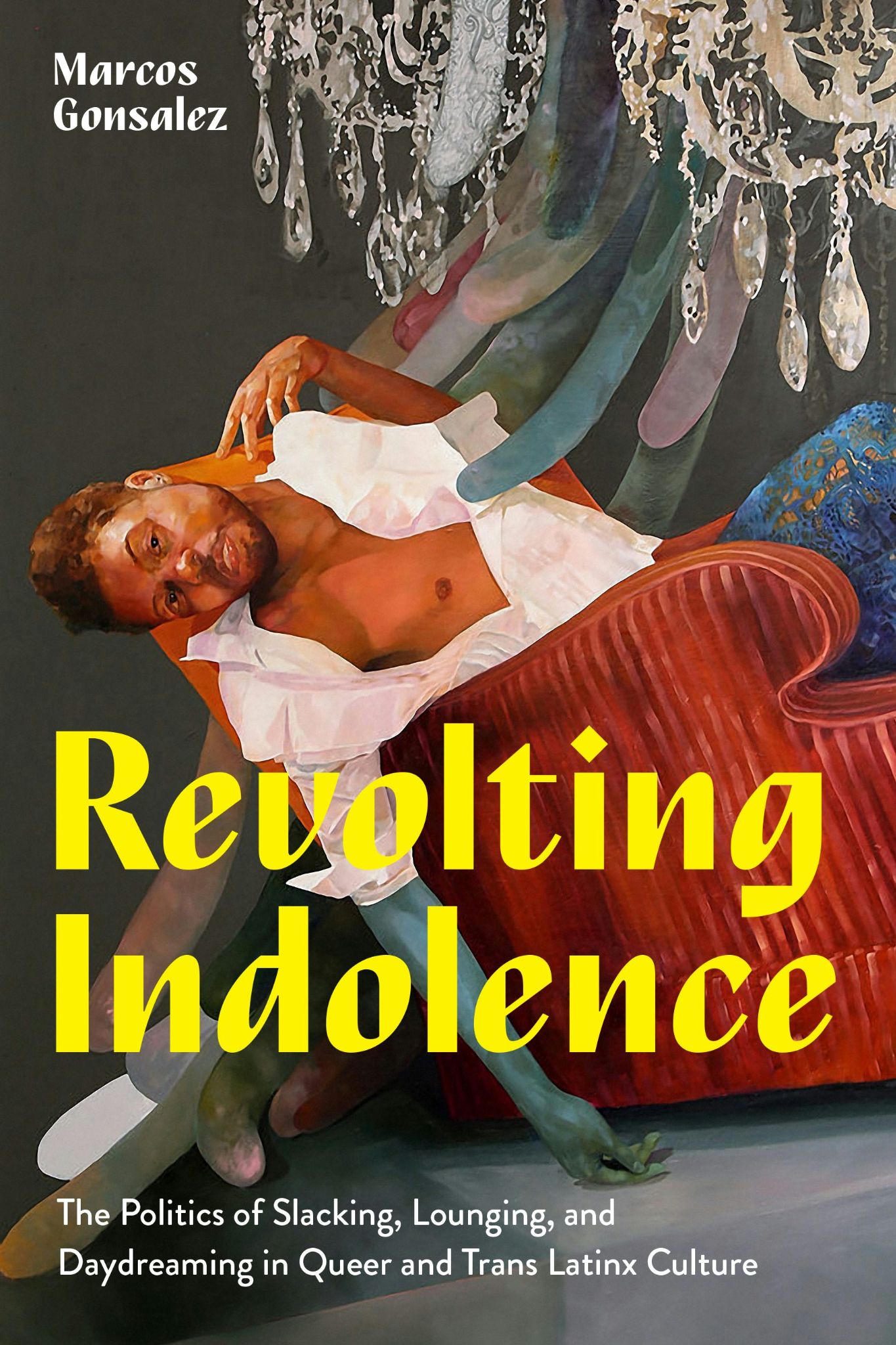

Revolting Indolence: The Politics of Slacking, Lounging, and Daydreaming in Queer and Trans Latinx Culture

University of Texas Press, 2024

189 Pages

$105.00

Reviewed by T Lim

A cigarette is passed between two performers before their nightclub number; an intrepid employee works at a slower yet more manageable pace than her more productive peers; a poem illustrates a day spent in the sunlit spot of a daybed. In reading Revolting Indolence: The Politics of Slacking, Lounging, and Daydreaming in Queer and Trans Latinx Culture, one might speculate how Marcos Gonsalez will constellate the aforementioned instantiations as pregnant with liberatory potential. Through Revolting Indolence, Gonsalez theorizes indolence as a style that materializes as “(1) flagrant refusals of work and capitalist productivism by nonwhite queer and trans subjects [ . . . ] and (2) the inventing of alternative aesthetic strategies, sensoriums, and world-making practices that imagine elsewhere from neoliberal, cisheteronormative, white supremacist capitalism.” Through his definition, indolence becomes doubly important in both its affordance of a queer/trans of color criticality to exploitative industry and in positioning generativity as an imaginally expansive tool from which to speculate, enact, and feel anti-work and post-work worlds.

The universality of indolence and its various refractions (laziness, lethargy, wanderings, etc.) surface through a precise examination of queer and trans Latinx culture. Throughout five chapters, Gonsalez weaves through the performances, works, and portrayals of various queer and trans Latinx artists to showcase how a liberatory indolence is not only possible, but uniquely potent at cultural sites where queerness, transness, and Latinidad imbricate. While Gonsalez guides the reader through more institutional(ized) sites of scholarly attention such as archival audio/visual materials and art installments, he also engages reality television and public art as vehicles that enact and circulate imaginations that trouble the mandates of hegemonic productivity. Through this capacious assemblage, Gonsalez imagines indolence as a deeply political queer of color practice, and powerfully ubiquitous in its appearance across countless contexts.

The first chapter engages Paris Is Burning (1990), a film which captures ball and house culture of 1980s New York, although Gonsalez’s focus on its outtakes avail insights that are both novel and resonant with his focus on indolence. The outtakes bring Angie Xtravaganza, mother of the House of Xtravaganza, into focus and with her the un-spectacularity that ballroom and house culture have become known for. Gonsalez transformatively uplifts activities such as Angie Xtravaganza’s lackadaisical shimmying and chit chatting by understanding such acts as ripe with a liberatory indolent politic as opposed to marginalia that failed to make the filmic cut.

Centering the works of Reynaldo Rivera, rafa esparza, and Gabriela Ruiz, the second chapter shifts from the videographic operability of indolence to the photographic. Here, Gonsalez astutely addresses a paradox in this project: in surfacing mundane and indolent subjectivities, he troubles the invisible and peripheral conditions which often produce such subjectivities. Gonsalez responds to this contradiction by establishing how photographs amber scenes of lounging to confer an intensification and legibility of the indolence they exude. In doing so, this chapter accomplishes a showcasing of liberatory indolence even in its stillness.

The 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting becomes the mournful yet generative subject of the third chapter, in which Gonsalez looks to the works of Maya Chinchilla, Ray Guzmán, Edgar Gomez, and Justin Torres. A stewarding through the literature produced in commemoration of this tragedy refuses a totally somber remembrance and vivifies visions of Latinx nightlife as a fleeting yet palpable refuge from anti-queer and-trans violence. Poetry becomes a labor in fantasy and memory, where anti-queer, -trans, and -Latinx oppression intermingle with recollections and visions of pleasure, elucidating the capacity for queer and trans Latinx joy to persist and return.

For the fourth chapter, Gonsalez turns to televisual media in his attendance to former RuPaul’s Drag Race (2009-) contestant and fan favorite Valentina. The glamorous kookiness and penchant for delusion that Valentina channels distinguishes her from other competitors on two levels. First, it empowers her to disrupt the neoliberal rhetorics of minoritarian uplift and bootstrap work ethics. Second, it offers a glimpse into her imaginal world, one where indolences inform dignity and fabulosity, and balk at hegemonic, assimilatory logics to ostensibly enfranchise queer and trans Latinx subjects. By examining Valentina’s drag as a devotion to queer and transfemme Latinx artistry, Gonsalez catalyzes a rigorously political understanding of her drag as something which transcends the capitalist motivations of the television show it is platformed by.

The works of Justin Torres and Sarah Zapata come to the fore in the final chapter, in which Gonsalez explores the textures of indolent queer and trans Latinx subjectivity. Gonsalez emphasizes touch in order to theorize upon divergent tactilities as presencing the existence of multiple and other(ed) worlds. Textures such as worm-filled mud in Torres’s We the Animals (2011) and the fuzzy surfaces of Zapata’s installments activate a tactile sensefulness, one conducive for slowing down and daydreaming. The salience of counter-hegemonic, liberatory pleasure becomes the culminating point of this chapter, one which enriches the characterization of indolence as requiring imaginative figurations of labor as being worth the commitments it demands.

In the final section of his project, Gonsalez discusses how COVID-19 galvanized a transformation in how people regarded themselves as productive, laboring subjects. Most saliently, Gonsalez brings attention to a global effort by employers to end remote work and return to a spacetime of in-person industriousness. The condemnation of slowing down and indolence by those in power is represented by the adage: “Nobody wants to work anymore.” Rather than a criticism, Gonsalez recasts such a statement into an invitation, his final comment beckoning readers to ask: what comes next? Given the consistent gesturing towards the world-building capabilities of a liberatory, indolent politic, what may come next—and the value of this book—is a continued que(e)rying of what worlds become possible when we resist unsustainable, capitalist productivity. This text not only provides rich theoretical and methodological insight into how scholars may recognize queer and brown strategies to resist capitalism. It also peeks into worlds that are possible and potent in their indolent reconfiguration of labor: it beckons others to share in these visions and engage the comportments that materialize them.

A cigarette is passed between two performers before their nightclub number; an employee works at a slower, more manageable pace than her peers; a poem illustrates a day spent in the sunlit spot of a daybed. In reading Revolting Indolence: The Politics of Slacking, Lounging, and Daydreaming in Queer and Trans Latinx Culture (2024), one might speculate how Marcos Gonsalez will constellate the aforementioned instantiations as pregnant with liberatory potential. Through Revolting Indolence, Gonsalez theorizes indolence as a style that materializes as “(1) flagrant refusals of work and capitalist productivism by nonwhite queer and trans subjects . . . and (2) the inventing of alternative aesthetic strategies, sensoriums, and world-making practices that imagine elsewhere from neoliberal, cisheteronormative, white supremacist capitalism.” Through his definition, indolence becomes doubly important in both its affordance of a queer/trans of color criticality to industriousness and in positioning generativity as an imaginally expansive tool from which to speculate, enact, and feel anti-work and post-work worlds.

The universality of indolence and its various refractions (laziness, lethargy, wanderings, etc.) surface through a precise examination of queer and trans Latinx culture. Throughout five chapters, Gonsalez weaves through the performances, works, and portrayals of various queer and trans Latinx artists to showcase how a liberatory indolence is not only possible, but uniquely potent at cultural sites where queerness, transness, and Latinidad imbricate. While Gonsalez guides the reader through more institutional(ized) sites of scholarly attention such as archival audiovisual materials and art installations, he also engages reality television and public art as vehicles that enact and circulate imaginations that trouble the mandates of hegemonic productivity. Through this capacious assemblage, Gonsalez imagines indolence as a deeply political queer of color practice, and powerfully ubiquitous in its appearance across countless contexts.

The first chapter engages Paris Is Burning (1990), a film which captures ball and house culture of 1980s New York, although Gonsalez’s focus on its outtakes avail insights that are both novel and resonant with his focus on indolence. The outtakes bring Angie Xtravaganza, mother of the House of Xtravaganza, into focus and with her the un-spectacularity of ballroom and house culture. Gonsalez transformatively uplifts activities such as Angie Xtravaganza’s lackadaisical shimmying and chit chatting by understanding such acts as ripe with a liberatory indolent politic as opposed to marginalia that failed to make the filmic cut.

Centering the works of Reynaldo Rivera, rafa esparza, and Gabriela Ruiz, the second chapter shifts from the videographic operability of indolence to the photographic. Here, Gonsalez astutely addresses a paradox in his project: in surfacing mundane and indolent subjectivities, he troubles the invisible and peripheral conditions which often produce such subjectivities. Gonsalez responds to this contradiction by establishing how photographs amber scenes of lounging to confer an intensification and legibility of the indolence they exude. In doing so, this chapter accomplishes a showcasing of liberatory indolence even in its stillness.

The 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting becomes the mournful yet generative subject of the third chapter, in which Gonsalez looks to the works of Maya Chinchilla, Ray Guzmán, Edgar Gomez, and Justin Torres. A stewarding through the literature produced in commemoration of this tragedy refuses a totally somber remembrance and vivifies visions of Latinx nightlife as a fleeting yet palpable refuge from anti-queer and -trans violence. Poetry becomes a labor in fantasy and memory, where anti-queer, -trans, and -Latinx oppression intermingle with recollections and visions of pleasure, elucidating the capacity for queer and trans Latinx joy to persist and return.

For the fourth chapter, Gonsalez turns to televisual media in his attendance to former RuPaul’s Drag Race (2009-) contestant and fan favorite Valentina. The glamorous kookiness and penchant for delusion that Valentina channels distinguishes her from other competitors on two levels. First, it empowers her to disrupt the neoliberal rhetorics of minoritarian uplift and bootstrap work ethics. Second, it offers a glimpse into her imaginal world, one where indolences inform dignity and fabulosity, and balks at hegemonic, assimilatory logics to ostensibly enfranchise queer and trans Latinx subjects. By examining Valentina’s drag as a devotion to queer and transfemme Latinx artistry, Gonsalez catalyzes a rigorously political understanding of her drag as something which transcends the capitalist motivations of the television show it is platformed by.

The works of Justin Torres and Sarah Zapata come to the fore in the final chapter, in which Gonsalez explores the textures of indolent queer and trans Latinx subjectivity. Gonsalez emphasizes touch in order to theorize upon divergent tactilities as presencing the existence of multiple and other(ed) worlds. Textures such as worm-filled mud in Torres’s We the Animals (2011) and the fuzzy surfaces of Zapata’s installments activate a sensefulness and sensuality, one conducive for slowing down and daydreaming. The salience of counter-hegemonic, liberatory pleasure becomes the culminating point of this chapter, one which enriches the characterization of indolence as requiring imaginative figurations of labor as being worth the commitments it demands.

In the final section of his project, Gonsalez discusses how COVID-19 galvanized a transformation in how people regarded themselves as productive, laboring subjects. Gonsalez brings attention to a global effort by employers to end remote work and demand the return to a spacetime of in-person industriousness. The condemnation of slowing down and indolence by those in power is represented by the adage: “Nobody wants to work anymore.” Rather than a criticism, Gonsalez recasts such a statement into an invitation, his final comment beckoning readers to ask what comes next. Given the consistent gesturing towards the world-building capabilities of a liberatory, indolent politic, what may come next—and value of this book—is a continued que(e)rying of what worlds become possible when we resist unsustainable, capitalist productivity. This text not only provides rich theoretical and methodological insight into how scholars may recognize queer and brown strategies to resist capitalism. It also peeks into worlds that are possible and potent in their indolent reconfiguration of labor: it beckons others to share in these visions and engage the comportments that materialize them.