Jill Dawsey and Isabel Casso, editors

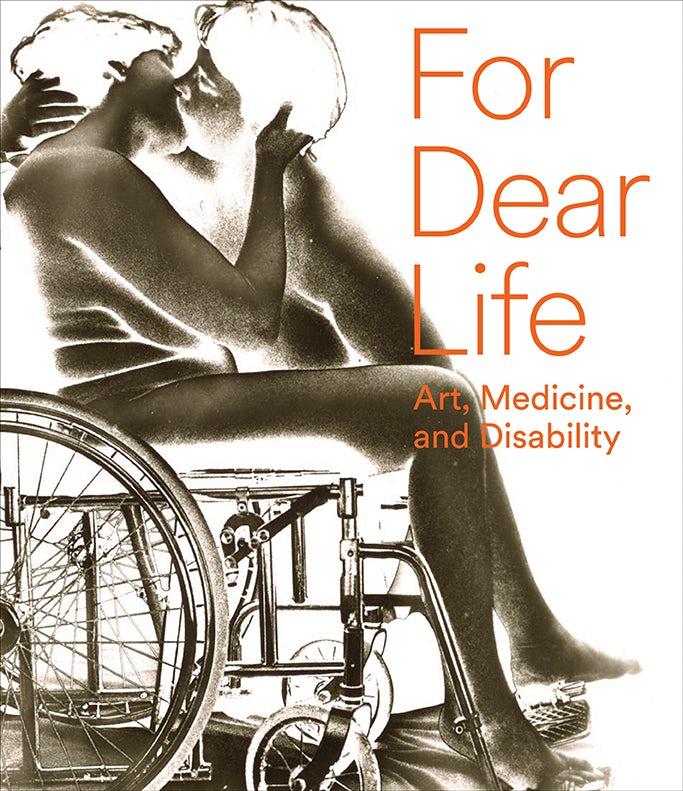

For Dear Life: Art, Medicine, and Disability

Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego

296 pages

$45.00

Reviewed by Alex Keith

For Dear Life: Art, Medicine, and Disability accompanies the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego exhibit of the same name, which narrates the history and intersection of art and disability from the 1960s through the contemporary COVID-19 era.

The collection begins with the premise that illness and impairment have historically been confined to the private sphere until the 1960s, when they started appearing in the public realm. By tracing the transition and evolution of illness and impairment through art, For Dear Life offers glimpses not only into the lives and works of the artists featured, but also into changing relationships of (dis)ability through art practices. In their Curators’ Preface, Jill Dawsey and Isabel Casso offer a broad definition that frames their understanding of disability, which they understand as including chronic and mental illnesses, as well as those without medical diagnoses. Their definition of disability allows for the inclusion of a wide array of disabled artists and their art, and presents the term ‘disability’ as an identity that people claim. Accordingly, the collection includes artists who identify as chronically ill or disabled, and nondisabled artists who imagined medicine as “a salve, a support, a plant, or a pill.” While medicine appears in the subtitle of the text, themes of identity, activism, and survival dominate the text.

The introduction begins with discussions of the women’s liberation movement, highlighting intersectionality and, specifically, how artists have discussed and portrayed miscarriages and abortion. These discussions are particularly apt in the wake of the Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization Supreme Court decision. The concept that the personal is political forms the basis of their discussion of art, identity, and disability. Through vignette-like biographies of several artists, the introduction takes the reader chronologically through several themes that define the collection, including race, gender, and location. Interspersed with images of art and art processes, the introduction moves from references to Frida Kahlo to the disability justice movement, the AIDS epidemic, and 2016 Black Lives Matter protests. The moments they chose to discuss offer a concise history of the past sixty years, grounded in how artists understood disability amid national and international events. The breadth of timescapes and artists mentioned speak to the varied arts and artists surveyed in For Dear Life. With an attention to intersectionality and various types of art, the authors offer a survey of how artists discussed disability and survival through art.

While the inclusion of diverse artists provides a broad picture of art and disability, little is explicitly mentioned about why certain artists are included and others are excluded. Although the introduction notes that the discipline of art history has only begun to recognize certain identities beyond simply another node of information about the artist, minimal biographical information is provided about each artist. Likely, space constraints impacted the decision to limit the amount of information provided. Though brief, the text’s descriptions offer both biographical details and insight into the artists’ ethos. For example, the section on one of the first artists discussed, Yvonne Rainer, includes quotes from an interview with the artist offering insights into Rainer’s own understanding of her work. The images and prose offer glimpses into the exhibition and encourage the reader to visit and see the artworks in person.

Overall, For Dear Life’s focus on disability, illness, and art argues that artists have consistently used various mediums to force such discussions into the public sphere. The book’s range from the 1960s to the 2020s is ambitious. To survey so many decades, each with its own historical and cultural moments is no easy task. Yet, the book successfully spans the decades. By culminating in the present moment, the book invites readers to reflect on their own experiences and perceptions of illness and disability in addition to how such reflections were impacted by the pandemic which influenced perceptions of illness, medicine, and disability. More attention to COVID-19 and other contemporary events would have been a welcome addition. The collection’s primary focus on Los Angeles and Chicago also provides a rich geographically context to consider how and why artists engage with art. The two cities chosen each have their own long histories of art activism providing rich backgrounds to explore the intersections of art, and disability. Still, I am curious about the more international connections between artists: how are artists thinking about illness and medicine across geographic borders? Are they building coalitions, traveling, and collaborating with one another?

The rest of the book includes four essays. The first essay, Sami Schalk’s “Emory Douglas and the Black Disability Politics of His Revolutionary Art,” recounts the discussion of disability politics represented through Douglas’s work in the Black Panther Party’s newspaper. By focusing on disability politics as represented in the Black Panther Party’s newspaper, Schalk historicizes the intersections between disability, race, and social justice. Dodie Bellamy’s “Lynn Hershman Leeson: Obfuscated Self-Display,” discusses breath and survival in Lynn Hershman’s work. David Evans Frantz’s “Sick Jokes, Blasphemous Rumor, and Fabulous Antics: West Coast Artists Respond to AIDS,” highlights the work of various artists in the 1980s and 1990s. Frantz foregrounds the agency of artists, often queer artists, who use humor and play as tools of resistance. Amanda Cachia’s “Here’s Looking at You: Disability Art at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century,” focuses on the expansion of disability justice, highlighting how queer artists, and artists of color advance the movement. By ending with discussions of disability justice advocacy, For Dear Life demonstrates how histories of survival and activism inform contemporary efforts. Taken together, the four essays complement the exhibit well, underscoring its themes of survival, identity, and illness.

Nonetheless, the text remains a purposeful and well-studied companion to an intentionally curated exhibit on disability, art, medicine, and survival. On its own merits, For Dear Life alone offers a well-informed historical frame of disability justice and the intersections of art and illness. It offers a chance to reflect on our own understandings of disability as well as the role of both art in offering representations of disability and the role of COVID-19 in shaping national conversations about disability.

The universality of indolence and its various refractions (laziness, lethargy, wanderings, etc.) surface through a precise examination of queer and trans Latinx culture. Throughout five chapters, Gonsalez weaves through the performances, works, and portrayals of various queer and trans Latinx artists to showcase how a liberatory indolence is not only possible, but uniquely potent at cultural sites where queerness, transness, and Latinidad imbricate. While Gonsalez guides the reader through more institutional(ized) sites of scholarly attention such as archival audio/visual materials and art installments, he also engages reality television and public art as vehicles that enact and circulate imaginations that trouble the mandates of hegemonic productivity. Through this capacious assemblage, Gonsalez imagines indolence as a deeply political queer of color practice, and powerfully ubiquitous in its appearance across countless contexts.

The first chapter engages Paris Is Burning (1990), a film which captures ball and house culture of 1980s New York, although Gonsalez’s focus on its outtakes avail insights that are both novel and resonant with his focus on indolence. The outtakes bring Angie Xtravaganza, mother of the House of Xtravaganza, into focus and with her the un-spectacularity that ballroom and house culture have become known for. Gonsalez transformatively uplifts activities such as Angie Xtravaganza’s lackadaisical shimmying and chit chatting by understanding such acts as ripe with a liberatory indolent politic as opposed to marginalia that failed to make the filmic cut.

Centering the works of Reynaldo Rivera, rafa esparza, and Gabriela Ruiz, the second chapter shifts from the videographic operability of indolence to the photographic. Here, Gonsalez astutely addresses a paradox in this project: in surfacing mundane and indolent subjectivities, he troubles the invisible and peripheral conditions which often produce such subjectivities. Gonsalez responds to this contradiction by establishing how photographs amber scenes of lounging to confer an intensification and legibility of the indolence they exude. In doing so, this chapter accomplishes a showcasing of liberatory indolence even in its stillness.

The 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting becomes the mournful yet generative subject of the third chapter, in which Gonsalez looks to the works of Maya Chinchilla, Ray Guzmán, Edgar Gomez, and Justin Torres. A stewarding through the literature produced in commemoration of this tragedy refuses a totally somber remembrance and vivifies visions of Latinx nightlife as a fleeting yet palpable refuge from anti-queer and-trans violence. Poetry becomes a labor in fantasy and memory, where anti-queer, -trans, and -Latinx oppression intermingle with recollections and visions of pleasure, elucidating the capacity for queer and trans Latinx joy to persist and return.

For the fourth chapter, Gonsalez turns to televisual media in his attendance to former RuPaul’s Drag Race (2009-) contestant and fan favorite Valentina. The glamorous kookiness and penchant for delusion that Valentina channels distinguishes her from other competitors on two levels. First, it empowers her to disrupt the neoliberal rhetorics of minoritarian uplift and bootstrap work ethics. Second, it offers a glimpse into her imaginal world, one where indolences inform dignity and fabulosity, and balk at hegemonic, assimilatory logics to ostensibly enfranchise queer and trans Latinx subjects. By examining Valentina’s drag as a devotion to queer and transfemme Latinx artistry, Gonsalez catalyzes a rigorously political understanding of her drag as something which transcends the capitalist motivations of the television show it is platformed by.

The works of Justin Torres and Sarah Zapata come to the fore in the final chapter, in which Gonsalez explores the textures of indolent queer and trans Latinx subjectivity. Gonsalez emphasizes touch in order to theorize upon divergent tactilities as presencing the existence of multiple and other(ed) worlds. Textures such as worm-filled mud in Torres’s We the Animals (2011) and the fuzzy surfaces of Zapata’s installments activate a tactile sensefulness, one conducive for slowing down and daydreaming. The salience of counter-hegemonic, liberatory pleasure becomes the culminating point of this chapter, one which enriches the characterization of indolence as requiring imaginative figurations of labor as being worth the commitments it demands.

In the final section of his project, Gonsalez discusses how COVID-19 galvanized a transformation in how people regarded themselves as productive, laboring subjects. Most saliently, Gonsalez brings attention to a global effort by employers to end remote work and return to a spacetime of in-person industriousness. The condemnation of slowing down and indolence by those in power is represented by the adage: “Nobody wants to work anymore.” Rather than a criticism, Gonsalez recasts such a statement into an invitation, his final comment beckoning readers to ask: what comes next? Given the consistent gesturing towards the world-building capabilities of a liberatory, indolent politic, what may come next—and the value of this book—is a continued que(e)rying of what worlds become possible when we resist unsustainable, capitalist productivity. This text not only provides rich theoretical and methodological insight into how scholars may recognize queer and brown strategies to resist capitalism. It also peeks into worlds that are possible and potent in their indolent reconfiguration of labor: it beckons others to share in these visions and engage the comportments that materialize them.

A cigarette is passed between two performers before their nightclub number; an employee works at a slower, more manageable pace than her peers; a poem illustrates a day spent in the sunlit spot of a daybed. In reading Revolting Indolence: The Politics of Slacking, Lounging, and Daydreaming in Queer and Trans Latinx Culture (2024), one might speculate how Marcos Gonsalez will constellate the aforementioned instantiations as pregnant with liberatory potential. Through Revolting Indolence, Gonsalez theorizes indolence as a style that materializes as “(1) flagrant refusals of work and capitalist productivism by nonwhite queer and trans subjects . . . and (2) the inventing of alternative aesthetic strategies, sensoriums, and world-making practices that imagine elsewhere from neoliberal, cisheteronormative, white supremacist capitalism.” Through his definition, indolence becomes doubly important in both its affordance of a queer/trans of color criticality to industriousness and in positioning generativity as an imaginally expansive tool from which to speculate, enact, and feel anti-work and post-work worlds.

The universality of indolence and its various refractions (laziness, lethargy, wanderings, etc.) surface through a precise examination of queer and trans Latinx culture. Throughout five chapters, Gonsalez weaves through the performances, works, and portrayals of various queer and trans Latinx artists to showcase how a liberatory indolence is not only possible, but uniquely potent at cultural sites where queerness, transness, and Latinidad imbricate. While Gonsalez guides the reader through more institutional(ized) sites of scholarly attention such as archival audiovisual materials and art installations, he also engages reality television and public art as vehicles that enact and circulate imaginations that trouble the mandates of hegemonic productivity. Through this capacious assemblage, Gonsalez imagines indolence as a deeply political queer of color practice, and powerfully ubiquitous in its appearance across countless contexts.

The first chapter engages Paris Is Burning (1990), a film which captures ball and house culture of 1980s New York, although Gonsalez’s focus on its outtakes avail insights that are both novel and resonant with his focus on indolence. The outtakes bring Angie Xtravaganza, mother of the House of Xtravaganza, into focus and with her the un-spectacularity of ballroom and house culture. Gonsalez transformatively uplifts activities such as Angie Xtravaganza’s lackadaisical shimmying and chit chatting by understanding such acts as ripe with a liberatory indolent politic as opposed to marginalia that failed to make the filmic cut.

Centering the works of Reynaldo Rivera, rafa esparza, and Gabriela Ruiz, the second chapter shifts from the videographic operability of indolence to the photographic. Here, Gonsalez astutely addresses a paradox in his project: in surfacing mundane and indolent subjectivities, he troubles the invisible and peripheral conditions which often produce such subjectivities. Gonsalez responds to this contradiction by establishing how photographs amber scenes of lounging to confer an intensification and legibility of the indolence they exude. In doing so, this chapter accomplishes a showcasing of liberatory indolence even in its stillness.

The 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting becomes the mournful yet generative subject of the third chapter, in which Gonsalez looks to the works of Maya Chinchilla, Ray Guzmán, Edgar Gomez, and Justin Torres. A stewarding through the literature produced in commemoration of this tragedy refuses a totally somber remembrance and vivifies visions of Latinx nightlife as a fleeting yet palpable refuge from anti-queer and -trans violence. Poetry becomes a labor in fantasy and memory, where anti-queer, -trans, and -Latinx oppression intermingle with recollections and visions of pleasure, elucidating the capacity for queer and trans Latinx joy to persist and return.

For the fourth chapter, Gonsalez turns to televisual media in his attendance to former RuPaul’s Drag Race (2009-) contestant and fan favorite Valentina. The glamorous kookiness and penchant for delusion that Valentina channels distinguishes her from other competitors on two levels. First, it empowers her to disrupt the neoliberal rhetorics of minoritarian uplift and bootstrap work ethics. Second, it offers a glimpse into her imaginal world, one where indolences inform dignity and fabulosity, and balks at hegemonic, assimilatory logics to ostensibly enfranchise queer and trans Latinx subjects. By examining Valentina’s drag as a devotion to queer and transfemme Latinx artistry, Gonsalez catalyzes a rigorously political understanding of her drag as something which transcends the capitalist motivations of the television show it is platformed by.

The works of Justin Torres and Sarah Zapata come to the fore in the final chapter, in which Gonsalez explores the textures of indolent queer and trans Latinx subjectivity. Gonsalez emphasizes touch in order to theorize upon divergent tactilities as presencing the existence of multiple and other(ed) worlds. Textures such as worm-filled mud in Torres’s We the Animals (2011) and the fuzzy surfaces of Zapata’s installments activate a sensefulness and sensuality, one conducive for slowing down and daydreaming. The salience of counter-hegemonic, liberatory pleasure becomes the culminating point of this chapter, one which enriches the characterization of indolence as requiring imaginative figurations of labor as being worth the commitments it demands.

In the final section of his project, Gonsalez discusses how COVID-19 galvanized a transformation in how people regarded themselves as productive, laboring subjects. Gonsalez brings attention to a global effort by employers to end remote work and demand the return to a spacetime of in-person industriousness. The condemnation of slowing down and indolence by those in power is represented by the adage: “Nobody wants to work anymore.” Rather than a criticism, Gonsalez recasts such a statement into an invitation, his final comment beckoning readers to ask what comes next. Given the consistent gesturing towards the world-building capabilities of a liberatory, indolent politic, what may come next—and value of this book—is a continued que(e)rying of what worlds become possible when we resist unsustainable, capitalist productivity. This text not only provides rich theoretical and methodological insight into how scholars may recognize queer and brown strategies to resist capitalism. It also peeks into worlds that are possible and potent in their indolent reconfiguration of labor: it beckons others to share in these visions and engage the comportments that materialize them.