Brenda Hillman

In A Few Minutes Before Later

Wesleyan University Press, 2024

200 pages

$26.00

Reviewed by Michael Mason

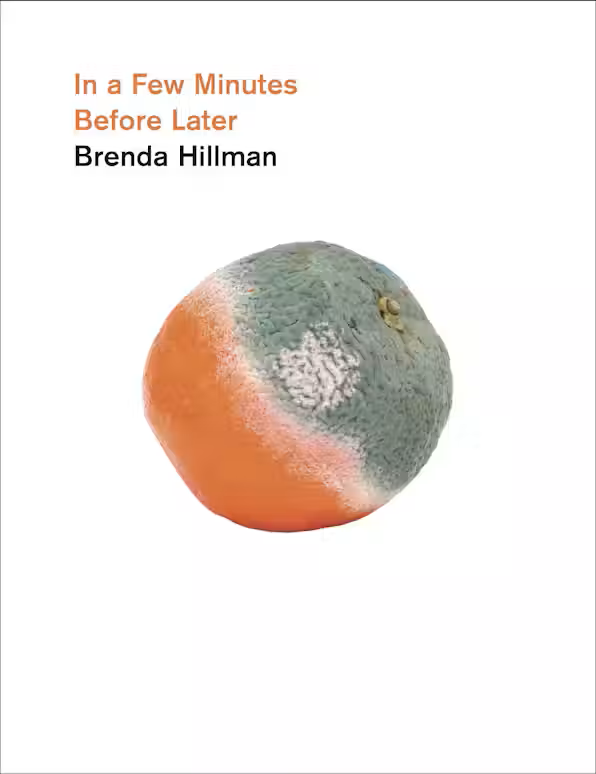

On the cover of Brenda Hillman’s new poetry collection, In A Few Minutes Before Later, an orange half-eaten by mold is almost perfectly divided, globe-like, into two hemispheres. The contrast between the bright orange rind and the verdigris penicillium makes the two colors equally vibrant, inviting ambivalence about which part of the image is more beautiful. The orange half, like the waning of some mouth-watering citrus ad, implicates human appetite in competition with the mold, so that we see ourselves living alongside a fungal otherness, sharing a common object. Hillman’s new poems speak into this simultaneity, not just through interspecies copresence, but across massive changes in temporal and dimensional scales. From mycorrhizal networks to the black hole Messier 87, In A Few Minutes Before Later wants to rehabilitate human temporality with more-than-human flows. This project is in sympathy with Jenny Odell’s Saving Time (2024), Odell’s critique of modern time and her search for alternatives to the tyranny of the contemporary clock. Just as Odell discovers new futures in fire-adapted habitats and cliff erosion, Hillman’s poems look around for other timescales, finding them in everything from mosses (with a nod to Robin Wall Kimmerer), to silent breaths in birdsong, to the flow of “hemoglobin pushing past science, math, the poetry section of the / brain.” Where Hillman’s previous collection, Extra Hidden Life Among the Days, elegized temporal scarcity in the human lifespan, these new poems praise temporal abundance hidden in the everyday, to show how “the future grows at different rates.”

This multifarious futurity wants to redeem the time of the poems’ composition. Hillman wrote the book from 2016–2021, and it’s tempting to transpose the book’s six sections onto that chronology, though the creeping ecological crises of the first section and the political crises of the second stand in for longer histories these poems address in sage exasperation, which the book’s alternate temporalities don’t console so much as counsel, with lessons learned from other life forms. It isn’t until the book’s fifth section, “The Sickness & the World Soul,” that poems begin ominously counting, accompanied by the COVID mortality rate. By the book’s final section, the 2020 California wildfires have put the poems to flight. Hillman and her husband, the poet Robert Hass, are forced to evacuate their home. A few minutes before later becomes a few minutes before it’s too late, and the poems grow desperate for futures. In “Escape & Logic,” grasses engulfed in flame are revealed to be “non-native / fescue & brome [ . . . ] brought by colonizing soldiers centuries back,” as though colonial ghosts were being routed by the wildfires. But crisis calls the poem back to its human center, the frantic effort to load the car and escape with one’s life and one’s love, the future unthinkable without them.

Hillman sets this apocalypse to June Carter’s “Ring of Fire.” Angels from Rilke and Blake attend, along with a host of other voices: Aretha Franklin, Allen Ginsberg, Lyn Hejinian, Amiri Baraka. The collection swells with quotations and dedications (see section III, “There Are Many Women to Cherish”), to newborns, to kids in Zoom classrooms, and especially to young poets, for whom the poems push form to fresh edges of semantic availability (see section IV, “For Writers Who Are Having Trouble”). Hillman’s extended techniques explode mise en page, “scattering” the lyric ‘I’ in the margins, and her elaborate punctuation play manipulates the tempo as well as the visual aspect of the lines. Irregular “breath circles” conjure airborne transmission in a dual sense: lockdown distancing protocols, but also the breath-based poetics of the 1950s and 1960s that Ginsberg and Baraka each made cases for. Hillman’s poems might be breathiest in their commas, which in places are strung together like quarter notes, and elsewhere take on glyphic lives of their own. But this isn’t the only way Hillman marks time while making it. Beginning with its title, the book blurs and distorts minutes and days, and any other clock and calendar units it can draw into its alchemy, as though, according to the hidden laws of Hillman’s poetics, the poems were dissolving habitual time – and with it, habitual feeling – in anticipation of futures our habits obscure.