Emily C. Bloom

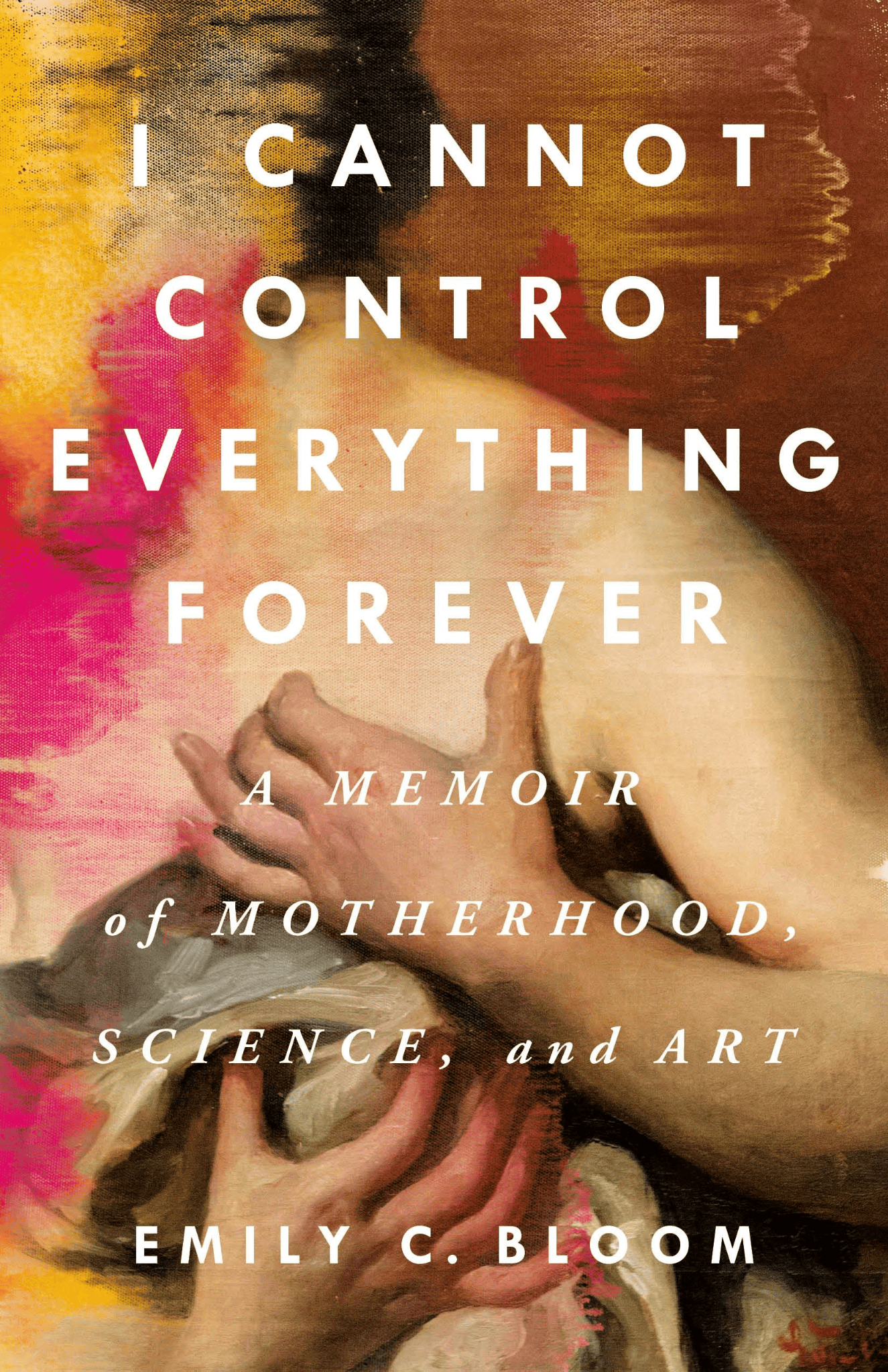

I Cannot Control Everything Forever: A Memoir of Motherhood, Science, and Art

St. Martin’s Press, 2024

352 pages

$29.00

Reviewed by Carlee A. Baker

I Cannot Control Everything Forever is an exhibition of Dr. Emily Bloom’s skill in blending memoir and scholarship, weaving narrative vignettes of deeply personal experiences alongside historical snapshots of medical-technological development and critical examinations of motherhood and disability. Divided into two sections—Pregnancy and Motherhood—Bloom carefully examines how matrescence in the modern era is now marked by technologies that provide endless streams of data, both prior to birth and after.

Bloom writes of parenthood in the age of “social media, surveillance technologies, genetic testing, and biotechnology” that “parents have unprecedented power in making decisions that will shape their children’s future—decisions about genetics, assistive technologies, and medical interventions.” Advances in medical technology intended to improve life for parents and children both have granted new powers to parents, resulting in the creation of a new parenthood—a new motherhood. “Scientific motherhood,” as Bloom refers to it, has instead placed a new set of expectations upon mothers. A good mom, in this era, “is now often defined not only in terms of traditional standards of nurture and care but, increasingly, by the degree to which a parent protects their child from environmental harms and works alongside a medical team to track development and intervene when their child goes off track.”

Where scientific motherhood is obviously fraught, Bloom brings in her personal experience to explore the complications of scientific advancement often thought of as an obvious good. Each chapter explores different technological or medical advancements for their complexities. Bloom uses Section One to explore risk and risk mitigation in pregnancy. Chapter One covers Bloom’s experiences with first trimester pregnancy and miscarriage. She discusses, honestly, the experience of losing a pregnancy in the first trimester, weaving her experience with at-home pregnancy testing with the scientific history of the pregnancy test and the ultrasounds. Bloom likens these two technologies to art, noting that “that all are crafted by people to reveal something about reality. They all make claims to truth [ . . . ] but they also alter the reality that they represent.” Pregnancy alters and expands one’s relation to the world, she suggests, and not exclusively in a cheerful way.

Chapter Two discusses genetic testing in the wake of the loss of her first pregnancy. Bloom brings the reader into her experience with an older brother with developmental disabilities. She points to the vague rhetoric used by doctors to mask the more insidious qualities of genetic testing: “The language that Dr. Patel used was vague—more information was better, she said. You can make an informed decision.” Bloom succinctly argues, “information is not neutral” and that “More knowledge does not translate to less risk.” These themes arise again in Chapters Three and Four in her discussion of genetic screening, gene editing, and IVF where she suggests that, “Technological advances in reproductive science do not reduce the role of decision-making and day-to-day care that falls heavily on women.” She considers genetic screening’s close connection to eugenics, incisively bringing detailed personal narrative to pair with discussions of the ethical implications of gene editing, posing a cutting question: in a future marked by the design of “perfect” children, “who bears the responsibility for imperfection?”

Having become pregnant again, Bloom transitions to discuss life after the birth of her daughter in Section Two: Motherhood. She brings us into the early moments of her daughter’s life and the barrage of standard infant medical tests. One such test was a hearing test, which Bloom’s baby girl had just failed. We are brought along to explore Bloom’s husband’s experience with deafness, which Bloom uses as an opportunity to explore Deaf culture and disability more broadly. Bloom forcefully confronts a medical system that prioritizes restoring patients to normativity: in her case, ensuring that her daughter can hear. Bloom walks through the history of the development of the hearing aid, paired with short stories of her daughter being fitted for new hearing aids every few months. Chapters Six and Seven narrate the experience of Bloom’s daughter being diagnosed with Type 1 Diabetes and the intense care involved in managing the disease. She discusses the difficulty of such care, especially as she handled such care alone, and the complications of her new role as a stay-at-home mom, discussing the evolution of the housewife into the stay-at-home mom with the advent of technology that makes the work of housekeeping more effective, but more invisible.

It is in Chapter Eight that Bloom discusses her cyborg, “motherboard” nature: “I hold [my child’s] biodata in my hand, rely on medical technologies, and the companies that create them, to perform the functions that would otherwise happen internally. I care for her and I care for her devices. I am part mother, part machine.” She, in this moment, returns to her opening gambit of fetal chimerism, where the boundary that separates mother and infant is blurry. The technologies that are keeping her daughter alive reconstitute the blurriness of this boundary out of the womb. As she considers the case in favor of replacing her daughter’s hearing aids with a cochlear implant in Chapter Nine, she considers the history of this technology and once again confronts the medical-industrial complex that enforces normativity in the form of audiologists who resist the use of American Sign Language (ASL) and insist on the restoration of hearing. Chapter Ten centers once more on the complicated nature of motherhood and the spinning of larger and more disparate webs of care. This is exemplified by Bloom’s decision to hire a nurse to accompany her daughter as she attends school for the first time. She watches carefully as her daughter becomes more a part of the world and explores the complexities of allowing herself to write about the complicated nature of motherhood. She concludes, “I have a web that I feel the compulsion to weave in order to feel less alone. This is my web. It is made of the same stuff that I used to make a life for my child. It is silk: the mother stuff.”

Bloom writes an extraordinarily compelling researched memoir that grounds scholarly discussions of medicine and motherhood in a deeply personal, moving, and refreshing manner. Without taking such a posture, she has engaged in a sustained, narrative exploration of the philosophy of science and technology in a manner that is stimulating, practical, and intensely personal. Her narrative is phenomenally detailed, heart-wrenching, and thought-provoking all at once. The weaving in of scientific development, also explored in a narrative style, to bolster the experiences she writes about throughout the text is a case study in making a text approachable and engaging to popular and scholarly audiences alike. While the emphasis on art seems to occur mostly in passing, often in narrative vignettes about experiences in art museums or pulling on literary examples she’s happened across in her research, the personality that she brings to scientific research would have you mistake these developments for art themselves. Bloom’s careful pontifications on medicine and technology and the all-consuming nature of motherhood are at once forceful and deeply caring, a necessary read for those invested in disability scholarship, medical and technological studies, or scholarship on modern motherhood.