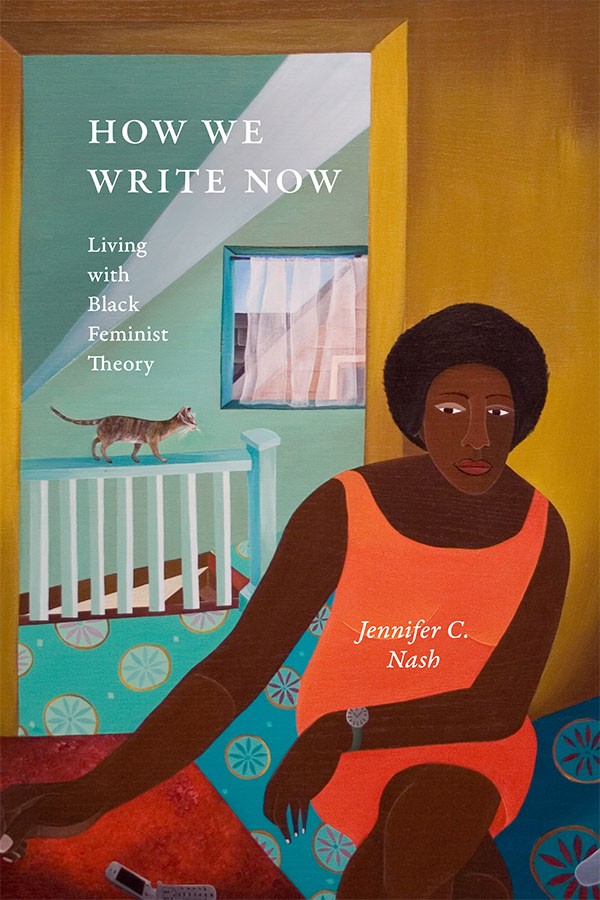

Jennifer C. Nash

How We Write Now: Living with Black Feminist Theory

Duke University Press, 2024

130 pages

$24.95

Reviewed by Montéz Jennings

In How We Write Now: Living with Black Feminist Theory, Jennifer C. Nash presents a stimulating and personal examination of academic writing through Black feminist theory. Nash is the Jean Fox O’Barr Professor of Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist studies at Duke University, editor of Gender: Love, and co-editor of The Routledge Companion to Intersectionalities and the Black Feminism on the Edge book series. She earned a PhD in African American studies at Harvard University and her JD at Harvard Law School. Each of her works (Birthing Black Mothers, Black Feminism Reimagined: After Intersectionality, and The Black Body in Ecstasy: Reading Race, Reading Pornography) has earned an award. Her most recent work, How We Write Now is as theoretical as it is autobiographical, created by Nash’s blend of genres. She writes candidly about her mother and grief while using her experiences as a case study to demonstrate Black feminist reconciliations with loss through what she calls “beautiful” writing.

There are four chapters each individually labeled. Chapters One and Two establish Nash’s theory, method, and the significance of this work. Chapter Three focuses on Black feminist use of the letter to name and describe loss, Chapter Four examines the photograph, closely observing the family photograph. Nash complicates the view of the photograph. The photograph is described as a broader representation and archive of Black loss and life. The photograph defends the dead. The familial photo centers those who share kinship and is in addition to the photograph because it functions as “object that stands in as evidence of intimate loss and that allows Black feminist theorists to get close to loss and to demand that their readers get close to losses that they may or may not understand as their own.” The family photograph reinforces kinship—whether real or imaginary. Lastly the conclusion introduces a query about the Black paternal figure in Black feminist theoretical archive while reinforcing beauty in Black feminist writing to reconcile loss. The book is Nash’s grappling with her personal loss and grief through Black feminist theory. Throughout the chapters, Nash centers the loss of her mother to Alzheimer’s. This framing allows Nash to discuss how loss is intertwined with Black feminist theories and writing while pulling from scholars such as Claudia Rankine, Elizabeth Alexander alongside Jesmyn Ward, Christina Sharpe, and Natasha Trethewey.

Nash opens the preface of the book with her mother: “In the time it takes me to write this book, my mother may lose her capacity to read this sentence. Every morning when I meet this work, I write against the cruel force of that realization.” This sets up our framework. It is our entryway to the exigence of this book. Throughout the book, we learn about Nash’s family—their history of Alzheimer’s, her parents’ courtship, life before her birth, and the relationship between Nash and her daughter. A line from the first page of the first chapter reads, “This book is also about a Black feminist frame of Black loss, and the voice through which that frame has been developed, circulated, and honed with a particular intensity in the period of Black Lives Matter.” Furthermore, this view and voice of loss is connected or in conversation with Black mothers’ “wake work.” Her first example is Rankine’s 2015 New York Times Magazine article “The Condition of Black Life is One of Mourning.” The detail she highlights is Rankine recalling the birth of her friend’s son, who before he was nursed or named, his mother declared she must get him out of the United States. The correlation between Black motherhood and expectant loss is ever present as Nash uses various examples (Covid-19, the murder of George Floyd, the Black Lives Matter movement, “The Trayvon Generation,” and Imani Perry’s Breathe) throughout the book.

In exploring these public and social phenomena, Nash writes about the ways these have shaped the public to understand and witness Black loss. However, Nash offers a counter in asking readers, writers, and scholars to consider the social, political, and communal aspects of loss. Nash informs readers that this work is nontraditional and experiential as it embodies beautiful writing while the beautiful writing is being constructed and studied as the book’s object. She uses the term beautiful as a form of evaluation:

I use it to describe the aesthetic properties of contemporary Black feminist theoretical work and to capture its ethical commitments, particularly its aspiration to move the reader, even as it might move the reader in a variety of ways or may not move the reader at all. This writing also provokes unmoved readers to perform the work of asking why they remain unmoved, to probe what might make them feel for – and with – the authors that perform this kind of writing.

The beautiful (the writing and voice referenced above) tracks how the writing works on those interacting with it. Nash makes the case that beauty is practice and loss should be treated as an aesthetic question. Beautiful writing allows the reader and writer to take a heuristic approach to beauty for reconciling loss and living with grief at multiple levels. Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, And Queer Radicals is an example of beautiful writing, according to Nash. Hartman’s work is not only beautifully written, but it emphasizes beauty as practice for freedom and merges “critical fabulation” and poetry to breathe life into these “characters.” Hartman works to grapple with loss through revisiting sites of loss and filling in blanks lost time via fabulation and speculation. She blends genres, creating a work similar to a scrapbook and a novel. Novels need characters and because she is using speculation to build into their narratives, they become characters based on people who lived. The additional examples are useful in Nash’s explanations of beauty as method, practice, and enactment in writing.

Overall, the book offers a conceptual framework for thinking about contemporary Black feminist writings’ dedication to sitting with and at the site of loss through beautiful writing. How We Write Now most certainly makes one reconsider the idea of beauty and how we employ writing practices. Nash takes simple terms like “beauty” or “eavesdropping” to assert new meaning and academic practice. For some, these concepts could be abstract. However, these abstractions are partly what make the idea of beauty as Black feminist method and “eavesdropping” as tactical listening function as thoughts surrounding Black progressive thought take liberties in development of Black futurity and examining Black loss. One of the book’s greatest strengths is Nash’s hybridity of thought and writing to enact the beautiful as well as the vulnerability. As much as this book is a guide, it is also a story and journey of Nash maneuvering through watching her mother lose herself to an incurable illness.

How We Write Now is a testament to the power of Black feminism. It is an extremely intimate project, yet readers rarely feel like an intrusion because we are invited guests instead of voyeurs discussing loss. This intimacy allows a gateway into exploring counterstories of Blackness related to pain as demonstrated through motherhood and loss. From the beginning, mentioning state sanctioned violence that conditioned a social narrative of anticipated loss, Nash recognizes the importance yet gave us this book for other types of Black loss. The text is a beautifully tragic mobilization of grief, loss, and pain that shows the shifting nature of remembrance, lived experiences, theories, methods, and practices.