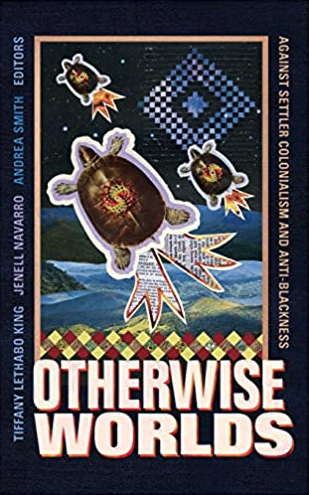

Tiffany Lethabo King, Jenell Navarro, Andrea Smith (eds.)

Otherwise Worlds: Against Settler Colonialism and Anti-Blackness

Duke University Press, 2020

386 pages

$29.95

Reviewed by Alina Scott

Otherwise Worlds: Against Settler Colonialism and Anti-Blackness is at once an intervention in Native and Black Studies and also a bridge between the two. Emerging from a conference of the same name, participants sought to speak to one another without “pretense of knowing, having mastered or being able to parrot the already accepted assumptions, tenets, and prescribed politics of each discipline.” The resulting collection does just that. This collection which features the work of key theorists in both fields seeks to contend with the “otherwise” forms of relationality that cannot easily be known. Otherwise Worlds presents an unconventional approach to interdisciplinarity. The goal is not to determine definitively how settler colonialism and anti-blackness relate to one another, but rather to learn in conversation with others about the two.

Historiographically, the editors argue that this intersection is usually articulated through the lens of solidarity, antagonism, or incommensurability. Each of which is insufficient. For that reason, this collection introduces a new way of relatability that creates space for what the authors term as a “stuckness” between Blackness and Indigeneity.

Each section builds on Édouard Glissant’s definition of “relation,” particularly that it “is the boundless effort of the world, to become realized in its totality, that is to evade rest.” Divided into four parts, the chapters speak to each other quite literally. Otherwise Worlds brings Black and Native studies together through traditional and non-traditional texts, methods of analysis, genre, and formats. This includes archival research, literary critique, interviews, and conversations, poetry, art, and lived experience(s). As editors Tiffany Lethabo King, Jenell Navarro, and Andrea Smith state in the introduction, these choices were intentional and valuable for opening the door to otherwise ways of being and relating.

In Part One, “Boundless Bodies” authors explore Black and Native bodies and flesh to ask how “we might free the flesh from the constraints and violence of settler colonialism and anti-Blackness.” Essays by Ashon Crawley and Denise Ferreira Da Silva, and a conversation between Frank B. Wilderson III and Tiffany Lethabo King, bridge Black, and Native studies through the abolition of the modality that states the distinction between the two is necessary, “reading the dead”, and finding entries for Black and Native studies to speak to each other. The conversation between Wilderson and King, narrated in the chapter titled “Staying Ready for Black Study,” is especially compelling. This format is different from an interview in that both speakers contribute and guide the conversation and leave room for not knowing. As such the conversation allows for opportunities to ask for clarification, and the chance to follow up in another conversation as is the case.

Part Two, “Boundless Ontologies” and Part Three, “Boundless Socialities” explore the historical intersection between Black and Native studies through the language of conquest, stolen land versus stolen labor, and the social relations between Blackness and Indigeneity. Cedric Sunray’s “Indian Country’s Apartheid” addresses identity policing, questions about federal recognition, and the role of antiblackness in Indian country. Chad Benito Infante’s “Murder and Metaphysics: Leslie Marmon Silko’s ‘Tony’s Story’ and Audre Lorde’s ‘Power’” brings Lord and Marmon Silko into conversation through their presentation of the “centrality of murder in Black and Native living and literature.” By discussing “retributive murder” or “cool fratricide” Benito Infante accomplishes yet another goal of the collective: to speak the unspeakable.

In “Boundless Kinship,” the final section, the authors discuss Black and Indigenous futures, liberation, and areas of connection through artistry, poetry, and other “possibilities of relationality.” In “The Countdown Remix: Why Two Native Feminists Ride with Queen Bey,” Jenell Navarro and Kimberly Robertson explore how the music and artistry of Beyonce’s Lemonade album provide room for critique of settler colonialism and state violence. This analysis centers Black and Indigenous feminisms and the bringing to the fore the significance of art, Black and Native motherhood, and radical kinship between these relations. Similarly, Navarro and Robertson’s “Mass Incarceration since 1492” builds on literature concerning the mass incarceration of Black and Indigenous people and extends the timeline to the first arrival of Columbus. The collaborative project brought together the creative work of Indigenous artists in the Los Angeles area to draw attention to the mass incarceration of Indigenous people.

This collection will be generative in both the fields of Native studies and Black studies and useful far beyond the two disciplines. This collection is truly a conversation between disciplines and paves the way for new ways of relating to one another. Otherwise Worlds is a compelling collection that does what it sets out to do.