George C. Wolfe

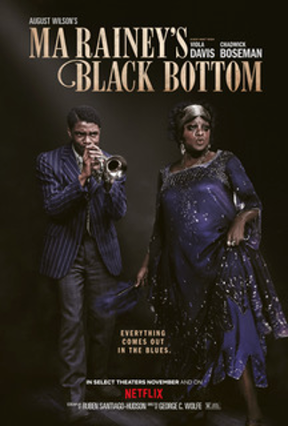

Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (2020)

Escape Artists Productions, LLC

94 minutes

Reviewed by Taylor Johnson Karahan

Traveling back to a sweltering summer Chicago day in 1927, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom showcases a group of Southern blues artists on their journey north to record their music. The film adaptation of August Wilson’s play of the same name stars Viola Davis as brash blues legend, Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, and the late Chadwick Boseman in his final acting appearance as the troubled trumpeter, Levee Green. Through an intimate window into the clash between southern Black artists’ expectations of autonomy and northern white recording studios’ exploitative intentions, director George Wolfe creates “a human event” symbolic of the Black American experience in the early twentieth century.

The movie opens with a vivacious performance. Ma Rainey, comfortably at home in the southern Black blues culture she helped establish, thrives in a hot show tent. Invoking the disorienting experience of the Great Migration, in which millions of southern Black people moved to the industrialized North in search of opportunities, the film then transitions out of Ma Rainey’s comfort zone and into its primary location of industrial Chicago. In the beautifully recreated “Black Metropolis” of the historical Bronzeville neighborhood, we enter Ma Rainey’s world of upended social conventions. Like her supporting band and white record producers, we are left waiting for the titular character to appear. Where is Ma Rainey? She’s coming, she’ll be here any minute. Traveling across the country to perform and record as an independent southern Black woman, the “Mother of the Blues” directly challenged 1920s notions of femininity and womanhood. She refused to remain in the domestic sphere, she refused to take orders from men, she refused to rush herself to meet anyone’s schedule. Ma Rainey made a career by breaking conventions, and she wasn’t going to let the ones in the big city bend her.

In the quiet, intervening moments of the film, Davis portrays Gertrude’s vulnerable interiority, in stark contrast to the ferocity and commanding presence Ma Rainey shows to the public. Donning her distinctive makeup that “looked like greasepaint” and with a “mouthful of gold teeth,” Davis and costume designer Ann Roth brought the character to life, refusing to sideline Rainey’s working-class background, vulgarity, and challenge to Black respectability. Headlined by women like Ma Rainey, blues was designated a disreputable musical genre because it presented and embodied working-class Black sexualities and problems that were the collective lot of Black people. As Angela Y. Davis has argued in Blues Legacies and Black Feminism (1998), blues emerged in the 1880s as the musical expression of post-slavery realities. Though emancipation brought little economic change to most African Americans, newfound autonomy in travel and the choice of sexual partners and relationships were the most tangible articulations of freedom. The film shines a spotlight (literally) on Ma Rainey’s articulation of her autonomy, even though she recognizes she is in Chicago to be exploited. “They don’t care nothin’ about me. All they want is my voice,” She says. “Well, I done learned that. And they gonna treat me the way I wanna be treated, no matter how much it hurt them.” Portraying her unyielding artistic vision, a challenge to patriarchal ideology, and acrobatic navigation through the racially exploitative music industry, the film showcases why Ma Rainey’s legacy continues to endure.

Personifying dreams of grandeur crushed by industry exploitation, Levee Green is a tragic blues character. A talented, up-and-coming trumpeter, he has grand ideas to modernize Ma Rainey’s music but lacks the authority to implement them. Boseman’s final performance is a testament to his profound acting skill and commitment, and the film is dedicated to his memory. Though he was undergoing chemotherapy treatments during filming and must have been under immense physical and mental stress, he throws his full weight into the challenging role, refusing to shy away from its more frightening elements. Levee wants what was promised to him: if he has talent, if he has ambition, he can become a star. Impatient and impulsive, his haunting childhood trauma has left him grounded only through his music. Boseman’s raw and unyielding portrayal crescendos in the film’s climax, when the heartbreaking consequences of Levee’s destabilization are revealed.

Due to Wilson’s conception of the story as a play, its translation to a film reads a little slow. While viewers unfamiliar with Wilson’s quotidian style may struggle somewhat with the pace, the exhaustive performances by Davis and Boseman as well as the rest of the supporting cast make it difficult to look away. Even during lulls in the action (of which the majority of the film consists), the film’s vibrant intimacy keeps us invested in its thoughtful blend of easy conversations and difficult storytelling.