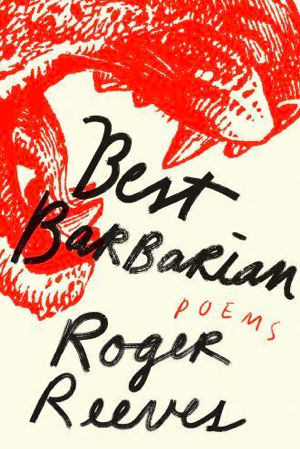

Roger Reeves

Best Barbarian

W. W. Norton & Company, 2022

120 pages

$26.95

Reviewed by Paige Welsh

Published in spring of 2022, Roger Reeves’s second poetry collection, Best Barbarian, is a lush text that summons liminality in the necropolis. These poems are layered palimpsest, the writing over of texts on the same sheet of paper. One can look closer at each poem and fall into a rhizome of interpretation. The poems are frequently elegiac, but perhaps the profound achievement of Best Barbarian is through its engagement with the mythos of the West, the West’s epistemic anti-Blackness. Reeves grows space for his voice by warping the linguistic boundaries posed by the canon. He has found the false seams between binaries. Reeves reworks death itself, so we may be shunted into an in-between space where history, the old legends, exists alongside seeds and Black children who will spin this heritage into a garden we cannot yet imagine.

Reeves calls us in with a bardic voice echoing Homer, strong, confident, as he knots together the anticipated images of poetry with contemporary scenes. As he writes in “Without the Pelt of a Lion”:

The dense wood, the Kurds, the rebels, and even the storm,

Sing of men and women without the pelt of a lion

Draped over their necks, walking out of a flood

With their young, their old sitting upon their shoulders,

Refugees of neocolonial conflict and climate change stream together as if they are emerging from the burning ruins of Troy. The lion’s pelt may be Heracles’s or Gilgamesh’s. The readings refract off of one another.

In the center of the book, the ten-page poem “Domestic Violence” runs river-like into an afterlife. It’s difficult to pluck out just a few lines. They all interlock and Reeves has used the old poetic effect of capitalizing the first word of every line. There is the story of the punctuated sentence and then the story of the line which contains an end and beginning. Sustaining the impact of this stylistic choice is impressive across ninety-six pages of poetry.

In the poem, Louis Till, father of Emmett Till, walks through the underworld with guides Ezra Pound and a woman who speaks as Audre Lorde, Lucille Clifton, and Gwendolyn Brooks all at once. Till then encounters “a queer parliament of the dead” that includes Sandra Bland, Freddie Gray, and Eric Garner amongst other Black people whose suffering textually replays itself when read or witnessed by the living. The chorus speaks,

“We are not permitted,” they said. “We are not

The dead of this dead. A different light. But go.”

And then I heard my name; well, not my name

But the name of my name, “Till, Till, Till.”

The repetition and reangling of words are characteristic of this collection. Reeves turns over the word ‘name’ and deftly orients the readers to spend time with the multitude in “Till:” the child himself, his father, the open casket, the photo in the newspaper, the act of tilling to change the land, to sow, to reap. A rider with a wound on his neck laughs.

Coupled with the skull, and the wound spoke

But not the speech of the mouth but the speech of reason

But not the reason of Plato, Virgil, Foucault

Or the stars maddening the night with their bursts

Or madness, their dying in the night’s hair,

But the reason of the spear that pierces

The skull and slides through the chin, letting

The darkness down, letting all the darkness down.

Here, Reeves has followed the West’s reasoning down to its conclusion: the tip of the spear that built an empire.

The collection does not offer a saccharine silver lining for the violence in the center. We don’t so much reemerge from the underworld, as transform it. Reeves hews open the rifts to make room for something new. The poem “Journey to Satchidananda” speaks of gold pouring into the cracks.

Beloved, my daughter—a window thrown

Open—her voice, gold filling in the cracked

Basketball court of me, announcing all

Nature, all nature will be dead for life soon.

The final line captures how the collection turns a paradox into land to stand on. In a reading for the Schomburg Center, Reeves notes that this line is indeed his daughter, Naima’s. It is fitting that in a collection that quilts together so much reference to antiquity, those classics the West schools us in, the line that captures the premise is a direct quote from a child who will inherit this legacy. The end of nature, the end of alienation, comes into focus by the end of the collection. As Reeves writes in the closing lines of the final poem, “For Black Children at the End of the World –And the Beginning”:

You are in a beautiful language.

You are What lies beyond this kingdom

And the next and the next and fire. Fire, Black Child.