Tina Post

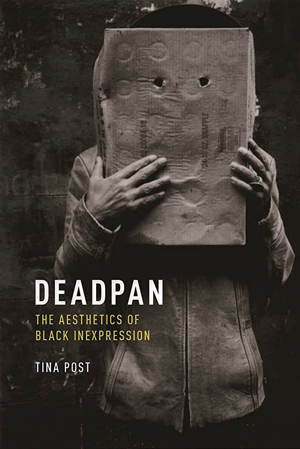

Deadpan: The Aesthetics of Black Inexpressions

New York University Press, 2022

269 pages

$30.00

Reviewed by: Olayombo Raji-Oyelade

Some books achieve significance in the time they were written, some command attention after they were written, and some remain timeless. I should note that Tina Post’s book Deadpan The Aesthetics of Black Inexpressions which arrives timeously in 2022 is indeed quintessential in temporality and in the significance of Black cultural studies. A cursory look at the Oxford English Dictionary for the meaning of deadpan gives the description of a “stoic, expressionless or impassive feeling used to describe humor that is done in a serious manner.” Post borrows the term to portray the internalized inexpression of blackness present in places where we may not find humor, as she foregrounds her analysis to accentuate the image, the aesthetics, the emptiness of the gaze and the interpretation of expressions seen.

Post engages the aesthetic field and its performances as a place where race and power relations play out through black cultural constructions. She quickly explains this in the introduction through Margaret Bourke-White’s LIFE Picture Collection taken on February 1, 1937. Although Post analyses two images taken at two different angles, the image shows a long queue of expressionless black people, all dressed in what could be interpreted as muted tones of blacks and greys, in line to get food and clothing from the Red Cross relief station. Ironically, the backdrop behind them pictures a happy white family riding in their vehicle, full of smiles. The ironic interplay between the dull black people waiting in line and the happy white family in the backdrop is further emphasized with the quote “There is no place like the American way,” becomes an iconic image because of the expressions of the factual black people who wait in line for food versus the scenario on the backdrop.

Before Post goes into the various spectacles that she engages in her work, it sounds as though she gives a warning when she says: “Like Robin D.G Kelley, I look to everyday performances that might seem perfectly reasonable, if not necessarily relevant and to those artworks that elucidate how…what appears to be merely compliance or complacency is usually more complicated, and that resistance and contestation can take many different forms.” She says this to note that she highlights instances in places (un)imaginable where black illegibility and opacity are found. The 270-page book is divided into five chapters. It adds to Black scholarship as it contributes to the ways black subjects perform under visual parameters of racialization. The images are powerful and as spectators, Post indulges in each of the chapters for us to engage with the “inexpressions”, and the combination of visibility and withholding as it is embodied within the images/subjects.

Chapter One, titled “Subjectivity and Self-Specimenization”, uses the image of Joe Louis, a heavyweight boxing champion, as a point of departure to depict a familiar face that was deadpanned and often associated with respectability. She argues that the stoic face and “inexpressionable” demeanor of the black subject who desires respectability has to invariably be a specimen or be under surveillance. Respectability is presented in the performative act of “self-distancing” from the gaze and modern subjectivity. At varying levels, Post brings documentary photographs by J.T Zealy, Alexander Gardner, Arthur Rothstein, Marion Walcott, Richard Avedon, and Rashid Johnson to confirm the black subject’s “self-reflexivity” in their engagement with the gaze (camera).

In Chapter Two, “Minimalism and the Aesthetics of Black Threat”, Post takes up through Hortense Spillers’ gendered binary an analysis of the gendered interpretation present in the deadpan. The invisibility of the black subject runs through black-centered discourses; therefore, inexpression becomes an added layer of questioning. The inexpressive black man is often assumed to be a threat while the inexpressive woman is invisible yet hypersexualized. “Loom” and “threat” are two words to take note of in this chapter as one does not exist without the other. The New Oxford American Dictionary defines “loom” as a “shadowy form, especially one that is large or threatening”. In this case, Post presents it as a vague yet exaggerated appearance which is linked to threat and opacity. Borrowing from Brian Massumi, “threat” is described as an affect and “the anticipatory reality in the present of a threatening future.” Both images of Don Cox are used as “specimen” in the interpretation of looming. The presentation of his stance, his downturn moustache, his large eyes, and thick eyebrows all corroborate his appearance as a “large, dark figure on the margin”, threat. The idea of black inscrutability as a threat which is espoused in this chapter, is also made edifice in Michael Fried’s “Art and Objecthood” as the charges that he presses against minimalist art is synonymous to the discourse that surrounds black subjects. The minimalist object is further elucidated through Saidiya Hartman’s analogy of subject and object at the same time. This analogy in the paradigmatic scrutiny of black threat is examined through the works of Adrian Piper, Martin Puryear, David Hammons and Roberts Morris’ life size minimalist sculpture and performance.

The title “The Opacity Gradient” gives utmost accuracy to the salient point Post makes in the third chapter. The word “opaque,” suggests that which is blurry, present but not completely seen, and contrasts with “transparency,” which according to Post entails “to see the invisibility of the black subject without simply creating hypervisibility”. Post refers to the figure of Sheryl Sutton, her performative iterations and aesthetics as transparent because her character on stage was so quiet that she could go completely unnoticed but was present. Between the dual-shapeshifting process of opacity and transparency, Post presents three other aesthetic schemes of gradient that span across racial bodies; sheerness, obscurity and awayness.

“Excess and Absence or, The Negro Believes_____” opens the fourth chapter with Paul Laurence Dunbar’s 1896 poem “We Wear the Mask” which makes reference to Post’s mention of visibility and withholding. The mask is full of false expression which hides the real expression of the face behind the mask. Through analyses of the dramatics of Young Jean Lee’s The Shipment and Brandon Jacob Jenkins Neighbors, Post points out the excessive blackness in the racial stereotypes of the characters. She also notes in this chapter that “blackness is not only represented in theatrical forms, but is itself a theatrical form” in order to amplify the aesthetics of race.

Post concludes with a chapter on Buster Keaton’s deadpan, where she considers the expressionlessness and withholding that have originated within black cultural actors. The ways in which the white comedic film star and enactor of deadpan aesthetics, Buster Keaton, borrows from blackness is explored here. To put simply, he invoked some black aesthetics such as performances of expressionlessness in white imagination. Post does an interesting analysis here by allowing one to see what a reenactment of black expressionless could look like through the quotidian of whiteness. Overall, Post indeed gives us both sides of the coin and certainly does not leave any stone unturned.