Domino Renee Perez

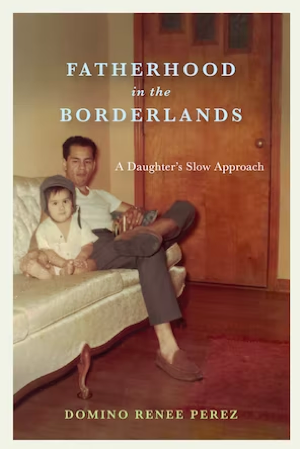

Fatherhood in the Borderlands: A Daughter’s Slow Approach

University of Texas Press, 2022

328 Pages

$29.95

Reviewed by Jack Murphy

A slow approach isn’t about slowing down. Rather, it’s about resisting the urge to speed up. When the demands of productivity ask us to act quickly, we often act too quickly, leaving behind the values that animated our research in the first place. Slow research asks us to recall the past that brought us to our inquiries; it asks us to shift our priority from “producing quantifiable output to creating meaningful connections to our work.” In Fatherhood in the Borderlands: A Daughter’s Slow Approach, Domino Renee Perez develops an ethics of slowness while musing on stories of the borderlands.

Perez’s research focuses on representations of paternity at the Mexican American border, bringing together the media of film, literature, and personal narrative. A professor in the Departments of English and Mexican American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, Perez builds upon her first monograph There Was A Woman: La Llorna from Folklore to Popular Culture (2008), as her muse shifts from her mother to her father. Here, Perez is interested in how Mexican American patriarchs in borderlands narratives “must actively work to maintain, reinforce, or in some cases substantiate their power” in response to the dangers of a “changing historical, cultural, social, or political landscape.” Perez’s work rejects definitive structure, which she associates with the requirement of literary research to be “objective” and “replicable.” To that end, Perez suggests that the reader find their own way: “So leaf through the book. Pick a spot or an image and start there.” With her encouragement, let us proceed slowly—mindful that our path is just one in a community of many.

Throughout Fatherhood in the Borderlands, Perez uses personal history alongside literary and film criticism. The book is divided into three parts: “Sourcing Authority,” “Instrumentalizing Indigeneity,” and “Fantasmas and Fronteras.” Each part is then broken down into three chapters, which are separately dedicated to film, literature, and personal narrative. In giving equal consideration to her own life, Perez challenges “the idea that the subjective or personal cannot be critical.” This intervention must not be understated. Firstly, the personal narratives facilitate her process of slow research. When scholarly work happens hastily, it can lack the type of consideration needed to defy the prejudices of the academy: “Reproducing without reflecting on the purposes or origins of certain writing practices can further entrench system disparities in the academy.” By writing about herself, Perez displays the merit of transparency, allowing the reader to understand the deep connections that she has developed towards her work.

Secondly, the personal narratives serve as critical turning points. In “‘No, I Am Your Father,’” Perez recalls going to see Star Wars (1977) with her father, which “fortified the already strong relationship” between them. From this experience, Perez draws nuanced conclusions about the lack of cultural representation in film as well as the purpose of film itself. For Perez, film is not about the “ceding of self,” but, rather, it is the place where she can rediscover the origin of her scholarly interest: “movies are where I find myself over and again, reminding me of where it all started.” Later, in “Nobody Ever Said We Were Aztecs,” Perez discusses the complicated nature of her Indigenous background. Family history and genetic testing confirm her Native American roots but offer little other insight: “these percentages tell me absolutely nothing about the tribe, band, clan, or Nation from which I am descended.” Again, Perez’s experiences prompt her interest in detribalization, spurring a “desire to understand why these relations were purposely obscured.” Finally, in “Family Fictions and Other Lies About the Truth,” Perez showcases her most beautiful prose, describing her family’s desire to move and explore: “My familia has lived in Tejas for more than five generations, but we have a tendency to wander.” In each case, Perez says, her family returns to their center: “We pack our bags and head for the Lone Star on the horizon.” This commitment to origin—amidst disparate strands of inquiry—exemplifies the slowness of Perez’s slow research.

In each section, Perez also studies a film or set of films. In “Ancianos not Abuelos: Making Space and Mediating Male Power,” Perez considers the role of senior patriarchs —namely, grandfather figures—in the films A Walk in the Clouds (1995), Real Women Have Curves (2002), and Quinceañera (2006). In these films, the anciano must oversee “the transfer of male authority to the next generation,” while also negotiating the “dominant cultural and socioeconomic forces against which Mexicans, Mexican Americans, and Chicanxs struggle.” Further, Perez navigates the racial terrain of each film, which often reify “the mainstream value of whiteness at the expense of Brown families.” In “Fatherhood, Chicanismo, and the Cultural Politics of Healing in La Mission,” Perez discusses La Mission (2009), a film concerning the “lives of a Chicano father and son who live in the San Francisco Mission District.” Their relationship becomes strained when Che, the father, learns that his son Jesse is gay. Analyzing a number of cultural symbols—most notably, the performance of danza azteca—Perez observes that Che turns to his Indigeneity for redemption. In other words, Che “finds curative power in various aspects of Native identity—both real and imagined—enacted through witnessing, singing, praying, and dancing.” Finally, in “Meta and Mutant Fathers,” Perez considers how Suicide Squad (2016) and Logan (2017) twist Western conventions established in the Magnificent Seven (1960). Each of these films invert the blanketly villainous stereotype of Mexican American characters, but Logan is most successful in capturing “the permeability of borders—racial, genetic, and geographic.”

Finally, each section features work of literary criticism. In “Fathers and Racialized Masculinities in Luis Alberto Urrea’s In Search of Snow,” Perez discusses the interactions between three Latinx men in Urrea’s novel. She argues that the “triangulation” of these principal characters “reveals how their performances of masculinity act on and influence each member of the group.” Later, in “New Tribalism and Chicana/o Indigeneity in the Work of Gloria Anzaldúa,” Perez echoes the sentiment that Anzaldúa’s work has been seldom critiqued compared to other theorists. Accordingly, Perez provides one of her most significant contributions, as she details why Anzaldúa’s “new tribalism is as flawed as it is beautiful.” Finally, in “Fathers, Sons, and Other (Short) Fictions,” Perez looks at two borderlands short story collections: Ray Gonzalez’s The Ghost of John Wayne and Other Stories (2001) and Oscar Cásares’s Brownsville (2003). For each work, Perez analyzes the narratives where characters interact with “border landscapes that are haunted by ghosts, their fathers, and even themselves.”

Fatherhood in the Borderlands is an important work for all scholars. Perez not only offers varied contributions to Mexican American studies but also presents an attitude towards scholarship that we should all consider adopting. At the beginning of her book, Perez compares the slow approach to lowrider culture. In this practice, “American-made automobiles are remade into Chicanx works of art” through a steady dedication “to rebuilding, refurbishing, and creative design.” In this sense, a slow approach to research is one that values personal investment and imaginative recreation. When our work ethic is too fast and too efficient, we drive by these possibilities. We forget the pleasure of slowing down to enjoy the view, and we forget the virtue looking back on the road that brought us here.