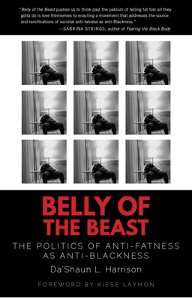

Da’Shaun L. Harrison

Belly of The Beast: The Politics of Anti-Fatness as Anti-Blackness

North Atlantic Books, 2021

123 pages

$14.95

Reviewed by Silvana Scott

Da’Shaun L. Harrison begins Belly of The Beast: The Politics of Anti-Fatness as Anti-Blackness by discussing the dismissal of the fat Black masc body in academic fields, writing “This book does not exist anywhere else in the literary canon” and calls for an abolitionist politic that understands Black and fat liberation as inextricable.

Harrison weaves various methodologies to bridge the gap between Black studies, fat studies, and gender and sexuality studies. Calling for a dissolution of the World, Harrison asks readers to think beyond current ontological and structural violence. Harrison centers the beyond in Chapter One, “Beyond Self-Love,” when they write, “Body positivity is benevolent Anti-Fatness.” Harrison cleverly displays how “body positivity” merely provides a facade of acceptance that is “an opportunity for Thinness to reroute…its hold on fat people’s collective liberation.” Instead, the “beyond” is a place “without qualifiers, conditions or labels meant to harm and subjugate our being.” Neither body positivity nor self-love will liberate because they are both in the structural violence of this World, one “in which the Slave/ the Other/ the Black are produced.”

Harrison theorizes on Desire Capital in the next chapter, “Pretty Ugly: The Politics of Desire,” to address the violence of anti-fatness and anti-Blackness. Desire Capital “determines who gains and holds both social and structural power… often predicated on anti-Blackness, anti-fatness, (trans) misogynoir, cisexism, queer antagonism.” Harrison capitalizes Pretty, Beauty, and Ugly as part of Desire Capital “through which people are marginalized for their Blackness, their gender(lessness) and their bodies” and consequently urges us to lean into insecurities and the Ugly as political tools.

Harrison asks “What would it mean for us to lean into Insecurity as a political tool in which we free ourselves from insisting that we perform ‘perfection’ and total confidence in order to advocate for collective liberation?” Tying Insecurity back to Desire/ability, Harrison highlights fatness as Blackness, where “fatness is formed as a coherent ideology through the creation of (anti) Blackness and therefore does not intersect with Blackness, but exists with Blackness itself—is what leads others to determining that fatness is unDesirable.” Wrapping up the chapter, Harrison ties in questions of Desire to forms of sexual violence, where the “Black fat… lives with the heightened fear of being hypersexualized while simultaneously never being desired.” Harrison reflects on Hortense Spillers’s theories of ungendering as they write the “loss of gender” is “an altered reading of gender for Black people—particularly and especially Black women—after slavery through the ‘ungendenring’ of their body.” Consequently, Harrison states that their personal assaults “… have all happened in conversation with misogynoir and the way in which men engage bodies that “belong” to Black women—even when those bodies actually belong to Black girls, Black boys, and Black adults.” Returning to Insecurity as a political tool, Harrison states we must wage war against the World and its ideas of health, Thinness, as the foundation of anti-Blackness and anti-fatness.

The following section, “Health and the Black Fat,” continues the conversation of Desire through historicizing the origins of health and wellness. Harrison writes that black people have never been granted wellness, health, and safety due to enslavement and its legacies. Drawing upon accounts of scientific racism, Harrison discusses “illnesses” made by white people to subjugate Black people. Resulting in the medical-industrial complex: “an institution built and sustained by race scientists and eugenicists dedicated to continued Death of Black fat subjects.” Thus, health “in name and inaction has always existed to abuse, to dominate, and to subjugate.” Similarly, the diet industrial complex seeks to subjugate and imprison fat bodies through exploitative capital ventures, advertisements, and ideologies.

Building off the causes for violence against the Black fat person, Harrison discusses in Chapter Four, “Black, Fat and Policed,” how state-sanctioned violence and murder against Black people are covered under anti-fatness and anti-Blackness. Recounting the death and murders of Eric Garner, Mike Brown, Tamir Rice, Walter Scott, Samuel Dubose, Alton Sterling, and George Floyd, Harrison writes that what most of them had in common alongside Blackness “was fatness or an otherwise larger body.” Citing Tamir Rice’s case, Harrison writes, “he was indeed larger than the average twelve-year-old—a fact that only matters if one believes the police have a right to murder Black people, or that police should exist at all.” Referencing the title of their book Harrison writes, “Black is fat; the Belly is attached to the Beast,” and citing Zakiyyah Iman Jackson, the state, “the Black as the Beast, and the Beast as the Black are essential to the maintenance of ‘the Human’—even and especially as the Black/Slave/Abjected are removed from Humanness.” Here, Harrison explains Black people are not dehumanized but rather become the “Beast of Humanity” where the Black fat is always already criminalized and policed. Harrison writes that policing is not just an institution, but a “Social agreement… for those who have a(n) (in) vested interest in the control of the black fat.”

The next chapter, “The War on Drugs and the War on Obesity,” discusses the continuation of the war on fat people and Black people after enslavement. Starting with the Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention (CDC) fabrication of “obesity,” Harrison says sedimented the “modern genocide of fatness and fat people.” Harrison then writes, “…the War on Drugs is the Black, and at the core of the War on Obesity… is the Black fat.” Like the War on Drugs, major institutions faked evidence about the “Effects of fatness or obesity as a way to criminalize and profit off fat people—especially the Black fat.” The violent medical, industrial complex is committed to seeing “Blackness and Black fatness as death,” fueling the “inherently anti-black system of policing that sees them as the deadly Beast that needs to be put down.”

Alongside abolishing systems of policing, Harrison stresses Gender must also be destroyed because “it can only ever reproduce cisheterosexist violence and within that… there will be antifat violence.” In Chapter Six, “Meeting Gender’s End,” Harrison surveys various Black trans people, all who are either trans men, transmasculine or non-binary, and asks them questions such as what is their journey into “trans ID” as a fat person, how has Gender played a role and how they feel anti-fatness shows up in predominantly trans spaces. Most of the participants discussed that they had to force themselves into the space, often “creating their own gender within gender because their fatness… denied them the ability to do anything but that.” Harrison highlights material realities, such as Fat, trans people not being able to findbinders or achieve equitable access to Gender affirming surgery. At the end of the book, Harrison writes in the last section, “Beyond Abolition,” that “at the root of revolution must mean cultural revolution and destruction of the sociopolitical institutions that hold these systems in place.” Harrison concludes that abolition cannot be the end, that destruction of the World must happen, where anti-blackness exists at its core. A future beyond abolition must be done collectively where “the caged bird is not freed from its cage; in that place, the cage never existed for the bird to ever be bound by.” Thus, moving beyond abolition means destroying the “World that produces the cage by which the Black fat is bound.”