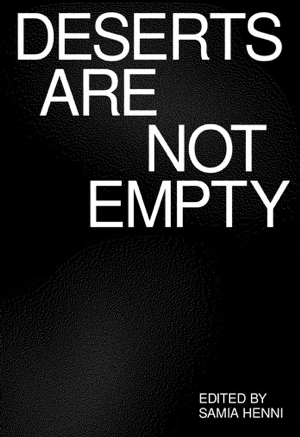

Edited by Samia Henni

Deserts Are Not Empty

Columbia University Press, 2022

384 pages

$23.00

Reviewed by Alhelí Harvey

A popular TikTok by user @rudyayoub breaks down the sonic, spatial, sensorial, and character tropes in Hollywood depictions of “arab countries.” Implied in these tropes is that the people of these lands live under some sort of imposed scarcity, that their lives are lacking. The backdrop to this trope is the idea that the desert itself is reflective of this: arid, dry, barren. Within a few seconds we, the viewers, understand that the desert is waste, and the people who live with it struggle because of it. This understanding of the desert is an Orientalist trope, what contributor Brahim El Guabli terms“Saharanism.” Building on the work of Edward Said’s orientalism, El Guabli elaborates that saharanism operates as “a universalizing imaginary and discursive practice about deserts, perceiving desert spaces as empty, dead, and inherently dangerous. It transforms deserts into death traps for immigrants, into sites in need of policing, and legitimizes all forms of destruction, from the material and immaterial extraction of resources and knowledge to the testing of lethal military equipment and the dumping of waste.”

Published as part of Columbia’s Books on Architecture and the City, the collection would be happily welcomed by scholars working on cultural landscapes, art history, literary studies, photography, film studies, and rhetoric. Further, the text’s geographical range is one that should not be overlooked, nor should it be dismissed as a collection that brings together various thinkers and practitioners working to unbuild this world to recover what it sought to destroy. While some readers may hope to find writing specifically on the Americas and may even expect to find essays on necropolitics in the desert, contributors to the volume are not interested in portraying desert landscapes as sites of death. Rather, it is a serious interrogation of how deserts come to be

known under a regime of emptiness, and the role of death as a principal protagonist in ensuring the perpetuation of such spatial imaginaries. Essays by Danika Cooper, Menna Agha, and Ariella Aïsha Azoulay will interest those looking for ways to rework archives. The conversations recorded between Desert Futures Collective, Archive of Forgetfulness, and the curators of Space Wars–an Investigation into Kuwait’s Hinterland exhibited as part of the Kuwait Pavilion at the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale–will most appeal to readers concerned with research and methods in collections and exhibits. Readers thinking across scale and about the colonial past of contemporary discourses and statecraft will find good company in contributions Paulo Tavarez, XQSU, Dalal Musaed Alsayer, Ala Vronskaya, and Timothy Hyde. Samia Henni’s introduction frames the volume and seeks to orient our attention toward how a regime of emptiness hovers over deserts and is a colonial, imperial enterprise used to evacuate our understanding of deserts as sites of meaningful life worlds.

The core of Deserts Are Not Empty is to disassemble the colonial logic within our most common understanding of deserts, from the lexical to the cartographic, as a failure to understand that people, the world over, call the desert home, and that the desert is not a wasteland. The contributors of this volume introduce us to a set of tools to unlearn these false visions of desert environments, from the Sonoran to the Saharan. The experience of reading the volume is much like the experience of attending a spirited event with sage and collaborators working across disciplines on the questions of place. Contributors provide poems in their mother tongues, often with specific typefaces meant to signal handwriting, accompanied by translations or other creative writing to open their chapters. These inclusions are part of the larger gesture of the volume to rethink what kinds of archives, literatures, and discourses invite us to relearn deserts. Interviews interspersed with collectives and essays create a sense of flowing in and out of conversion organically while also illustrating the centrality of each project’s call to consider the people and places erased under the “imperial desert effect” (Ariella Aïsha Azoulay’s analog to saharanism).

Overall, the essays provide specific historical and contemporary examples of how the idea of a “desert” has been employed as a spatial regime used to justify colonial projects reliant upon extraction of resources, disenfranchisement of indigenous populations, cultural genocide, and habitat destruction. The success of this spatial regime, contributors illustrate, lies in the belief that desert landscapes are empty and can only be made valuable once they are entirely transformed. Such transformations, Ariella Aïsha Azoulay shows in her examination of occupied Palestine, fashion settler colonial orders as those entities that make the desert “bloom”: thus, they unmake the empty void, collapse the displaced peoples whose lands have been stolen, lifeways attacked, and celebrate their right to take over in crafting a fruitful desert. Terra nullius is a continued state project of “taming” the unruly and supposedly empty desert to then display and document, stamped, sealed by bureaucrats, designed by architects and engineers, photographed for posterity, and disseminated to the masses. But Palestine is always still there, where it has always been, Azoulay reminds us. Likewise, the desert effect is not just the evacuating images of the Gobi, Sahara, or Sonora but an extensive discourse that proclaims a “right” to capture lands deemed empty. Such processes, the authors argue, unfold, and redraw Brazil’s Amazon, allow US corporations to establish exploitative company towns in Saudi Arabia, for tech giants to hide how their logistical fantasies are part and parcel of the displacement and forced labor of theTurkic peoples of China’s western regions, connects canals at the scale planetary hallucinations, and renders Antarctica’s ice sheets as timeless. For those looking for ways to explain what often feels unexplainable, and who want to expand their own ways of seeing places and the people who call those sites their home, Deserts Are Not Empty is an evocative, moving, accessible text.