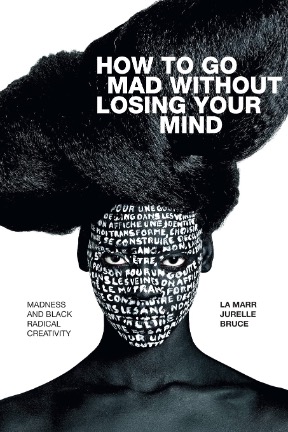

La Marr Jurelle Bruce

How To Go Mad Without Losing Your Mind: Madness and Black Radical Creativity

Duke University Press, 2021

345 pages

$28.95

Reviewed by Michael Cordova

Madness is not merely woven into someone. Madness is a praxis embodied through acts of resistance, subjection, will, and existence. In La Marr Jurelle Bruce’s How to Go Mad Without Losing Your Mind: Madness and Black Radical Creativity, we find ourselves in a dance with the mad as we explore the boundaries of a position that cannot be tethered towards the language of ‘Reason.’ In this instance, Bruce frames Reason as “a proper noun denoting a positivist, secularist, Enlightenment-rooted episteme purported to uphold object ‘truth’ while mapping and mastering the world.” In effect, a discursive weapon mobilized by the West to secure a ‘right’ way of engaging with the world. And through this critique, Bruce provides a ‘mad methodology’ towards engaging with a Western world that has long seen both the mad and the black as abject, instead presenting madness as a multilayered praxis of resistance and imagining. What we find in this book is an analysis of praxis, a snap, a click, a break, an opening, a closing, the middle, the beyond, the here, the now, the then, and the there.

Each pillar of madness embodies a differing discourse and weaves in other imaginings of artistic representation that parses through the legacy of black thought (reasoned or mad), starting with the archive. Bruce calls forth legacies that were never totally accounted for, like that of Buddy Bolden, the Father of Jazz. As we traverse the openings centered by Bruce, we find the story of Bolden to invoke the medicalized notion of the mad through the archive, as “[o]nly a single faded photograph, several sentences in legal and medical documents, three newspaper clippings, and a few dozen testimonies endures as primary evidence of Bolden’s life.” While the archive as an institution lacks in exploring any image of Bolden, Bruce weaves folklore, poetry, and fabulations that have inspired “artists to create into the hollow he leaves behind.” And so, this lack makes way for a new means of engagement with the archive, instead making a generative account, to which Bruce terms the ‘Bolden Effect’ in his reading of Bolden. This speaks towards the mad methodology at work, for instead of attempting to solidify the position of Bolden and make a stable figure from those that imagine, we instead approach with “radical compassion…across the uncertainty that separate” to (re)create the relations that might never have been. And thus, this medicalized madness and archival dearth, while seemingly capturing and empowering a certain narrative, must be overturned through the mad methodology to undo the empowered narratives and fabulate Bolden anew. Easily, this methodology, which centers black madness, speaks towards the greater archival work of thinkers like Saidiya Hartman, Katherine McKittrick, Hortense Spillers, and the work of countless renowned black feminists. Yet, this recentering of this relation through mad imaginings is a necessary twist that makes this embodied praxis of thinking with and through the archive, especially the medicalized, as finding some semblance of a ‘Self’ in a sea of ‘Other.’ Here, Bruce presents a praxis of care that serves to note the presence of another narrative. And so, care contorts and shifts into a multivocal discussion that explores more than the surface narrative we know, as even rage becomes a pivotal piece in the manifold analysis that Bruce proposes.

Bruce’s work also approaches critical and necessary discussions of rage, as he stretches mad methodology into literary analysis, examining black femininity beyond the unidimensional frames that Western structures have long made the norm. In his reading, he dedicates Chapter Three and Chapter Four to two key works of madness: Eva’s Man by Gayle Jones and Liliane: Resurrection of the Daughter by Ntozake Shange,respectively. Each chapter examines and dissects black feminine engagements with madness and the sort of psychosocial and phenomenal layers of the protagonist’s maddened experiences, but most central was a rereading of madness as rage. With Eva’s Man, instead of simply reading through the structural lens of black femme rage as structural/stereotypical normativity (i.e., pathological), Bruce asserts “that Eva’s madness [as rage] is not merely a site of abjection but also a locus of beleaguered agency” spoken through silence. In opposing fashion, Liliane’s madness can be read through her “bountiful, lyrical language,” which rests juxtaposed to Eva’s maddened silence. Each text dares to tell an ambivalent story of madness as rage when engaged with black femininity since Bruce yearns to make known both the multiply imagined and critically ambivalent layer to madness. There is not one singular reading, and thus, even when examining through the structure, a composite image of black madness is impossible, and what must be sought after is the “artistic window opening out toward infinite expanses of black creativity” made known through black madness. To read madness through merely the structural, predetermined fatalism that the West has made norm through the abject state of madness, Bruce instead reads and seeks agency through the mad.

Bruce’s last three chapters focus on important figures in present and past media: Ms. Lauryn Hill, Nina Simone, Kendrick Lamar, Kanye West, and Dave Chappelle. His work here, while a necessary and generative expansion into media studies, must also be seen for driving home the multiplicity at work within the text. I take to focusing on Bruce’s ‘ambivalent’ reading of media as an apparatus of both structured readings of black madness yet extending beyond the Reasoned regimes of constructing the mad. In other words, what we approach is an aesthetic (re)imagining that dares to chart against “madness-as-derogatory and takes up madness as a banner of resistance.” Through this reading, what we find is that individuals in media can be read beyond the normative strain that dares to flatten them to just stereotype—Ms. Lauryn Hill as ‘bag ladyhood,’ Dave Chappelle as ‘drapetomania’ embodied, or Charles Mingus’s ‘Angry Man of Jazz.’ Through these respective unflattenings, we denote the complex, lived, and structuralized experiences of individuals that are devalued due to their black madness. What we find instead is an approach toward something other: a life that is complexly the problem and against the problem, an in-between that dares to a generative model of otherwise proclamations. Bruce’s work dares to present a new (re)engagement with media, and through it, another means of imagining.

What we are left with in Bruce’s intervention into mad studies is a mad derivation in the discussions of the archive, literary studies, and media studies. We find ways to contort fields that have long been stabilized within a normative frame, and Bruce instead pushes differing imaginings that dare to twist away at simplified readings towards ambivalent readings. And through it, Bruce’s work sees to madness in its multiplicities, not tethered to structural readings, but merely being a presence that holds radical potentiality against the stable frame of Reason. Ultimately, we find a formulation of madness that dares only to be approached, for to engage in earnest with the text is to engage with madness. And Reason dare not let us into such a purview—not unless we feel mad. The text seeks to care, not just for madness, but particularly black madness and its generative and imaginative potentiality that is tethered to Western regimes of Reason. It is here that Bruce seeks to undo and provide sense (not logic) to a world that dares to undo black madness. Instead, he presents an intervention (which already has been carved out by black radical creatives) that allows one “to go mad without losing your mind.”