Gerard Bush and Christopher Renz

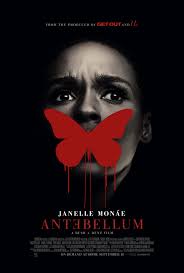

Antebellum

Lionsgate Films, 2020

Reviewed by Emma Hetrick

Antebellum, Gerard Bush and Christopher Renz’s 2020 film defies both genre and temporal setting. Divided into three acts that trouble conventional notions of setting and period, the film is a mixture of traditional enslavement narrative, horror, psychological thriller, with nods to science fiction and Afrofuturism. It begins with an extended long take that resembles traditional motion picture enslavement narratives. The camera first moves through a grove of trees, finding a young, white girl in nineteenth-century attire whose mother is calling to her from the steps of their plantation house. The camera continues to pane to different scenes on the plantation, including enslaved persons performing physical labor and Confederate soldiers hoisting the Confederate flag. The camera stops on the face of the film’s protagonist, Eden, played by Janelle Monáe, before following several Confederate soldiers on horseback as they chase after an enslaved man and woman running away. The haunting soundtrack stops as the tension of the scene heightens. The woman is captured with a rope around her neck, shot at repeatedly by a soldier while the man she was with yells in anguish, and the scene ends with her body being dragged at the end of the rope while the camera pans back to Eden. This opening scene sets the tone for the rest of the first act, which follows Eden as she labors on a southern plantation during the American Civil War.

The film takes its opening epigraph, a quote by William Faulkner that reads, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past” to heart. While laboring in the cotton fields, the enslaved persons look up at the sky in response to what sounds like airplane engines. On the way to a victory dinner, the Confederate soldiers who oversee the plantation chant “Blood and Soil” while holding torches, eerily resembling the neo-Nazis at the 2017 white supremacist rally in Charlottesville. When a young, enslaved woman who has newly arrived on the plantation speaks to one of the Confederates who has visited her in her quarters, he lashes out and claims to be a “patriot.” These nods to modern-day technology and white supremacy may only become clear upon a subsequent viewing of the film and suggest that the film is less like Twelve Years a Slave and more like an episode of The Twilight Zone.

The transition to the second act is startling, as Eden lying in bed next to the abusive Confederate general, becomes Veronica, also played by Monáe, a twenty-first-century academic, lying in bed next to her husband. In this act, other actors from the first act who play the white plantation dwellers, reappear as academic conference-goers, a flirtatious man in a restaurant, and a hotel receptionist. Jenna Malone, who plays the plantation enslaver in the first act, is now Elizabeth, a “talent scout” who shows an interest in Veronica’s work. Little does Veronica know, she’s interested in much more than her monograph on the intersections of race, gender, and class. In a reverse of the first act, there are nods in this section to Antebellum America. There are framed pictures of a plantation in the hotel Veronica stays at for a conference, and when she enters an elevator, the little girl from the opening scene is there in a period dress with sneakers, clutching a racist doll with a string around its neck. The act culminates with Veronica getting kidnapped by Elizabeth, who has followed her to the hotel. Transitioning acts once more, Veronica’s unanswered phone ringing becomes the Captain’s cell phone ringing as he sleeps next to Eden, who the viewer now knows is Veronica.

It seems a missed opportunity that Bush and Renz do not fully consider what modern-day enslavement could look like. Why wouldn’t twenty-first century Confederates want to live out their racist fantasies in the comfort of modern living? Instead, the film runs the risk of buying into the false historical reality of the Confederates by insisting on an authentic setting (Antebellum was filmed in part on an actual plantation) and period-appropriate material items (like a blanket that Veronica folds that belonged to an enslaved woman).

The film’s thesis is made explicit in the second act of the film, where Veronica orates at the conference, in front of a mostly Black audience, that “They’re [the white patriarchy] are stuck in the past. We are the future. Our time is now.” And indeed, she sees through this vision of liberation by burning her abuser and his Confederate compatriot and escaping from the plantation in a slow-motion sequence that blurs the temporal lines of the present and the Antebellum past of the American Civil War. Veronica emerges, in the film’s final twist, into the outskirts of a recreational area with bewildered bystanders, dubbed “Louisiana’s Premier Civil War Reenactment Park.” It turns out, Veronica and the other enslaved individuals were part of a nineteenth-century American South stylized Westworld, where privileged white people decided to recreate the past of their ancestors. Antebellum ends with the sign to the park’s entrance getting bulldozed, suggesting that there is a future possibility that is not beholden to the past. But it requires setting a fire and letting the past burn.