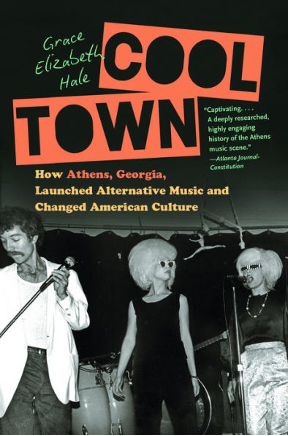

Grace Hale

Cool Town: How Athens, Georgia Launched Alternative Music and Changed American Culture

University of North Carolina Press, 2020

384 pages

$20.00

Reviewed by Coyote Shook

“Worried that people would not understand that the band’s name referred to a hair-style, not a bomber, [Keith] Strickland and [Freddy] Schneider bought fake fur muffs for Cindy Wilson and [Katy] Pierson to wear on their heads,” Grace Hale remarks as she describes the February 14th, 1977 debut of the B-52s in Athens, Georgia. “In the muffs, cat-eye sunglasses, dark blouses, and silky pants, the two women looked like drag queens.” Part music history, part a cultural analysis of intersecting identities in a town at the crossroads of the “New South” and the “New-New South,” Hale’s Cool Town traces the development of alternative music and bohemian culture building through a cast of “sissies and girls.” Fitting within critical questions of gender and sexuality that other musical-cultural historians such as Alice Echols and Stacy Wolf similarly approach, Grace Hale narrows her focus to the microhistory of a bohemian college town in the Deep South to trace the broader cultural tensions of the 1970s and ‘80s that the alternative music scene both responded to and influenced.

As a small-town Georgia sissy who grew up forty-five minutes from Athens, I found objectivity evasive as I read this text. I spent countless teenage weekends in the 2000s buying dusty records, eating slabs of grasshopper cake at The Grit, and navigating labyrinths of ugly sweaters and wigs in hole-in-the-wall thrift stores; the geography of Hale’s Athens and its music scene therefore felt familiar and disorienting at the same time. When Hale notes, “Today, bohemian Athens still works about as well as it ever did, nurturing a famous band here or there but always churning away at the less glamorous but arguably more important work of transforming the lives of suburban and small-town southern kids and giving them a vision of a bigger and more creative, open, and tolerant world,” I see myself reflected as a product of the punk-boho of the college town turned weird-cool terminus. Hale, similarly, makes no claims of objectivity. Indeed, she lived in Athens, Georgia as a University of Georgia student when much of the text takes place. She writes about Vic Chesnutt not just as an influential Georgia musician, but also as a person she knew as a friend. However, she avoids the temptations of utopian memory or writing a hagiography of a place where racism and conservatism still held outsized impact on the formation of a community. Rather than a love-letter to the universe of R.E.M., Pylon, and Reptar, Hale’s book offers a personal, nuanced, and deeply intimate historical perspective on the intersections of gender, sexuality, class, and race that converged at the twilight of the 1970s during an American transition from liberal counterculturalism to the neoliberal, conservative backlash of the 1980s.

Sexuality is problematized almost immediately in Hale’s framework. Bourgeois categories of sexual identity (such as “gay” vs “straight”) seemed immaterial to the back characters of the text: college students and white, suburban southerners seeking to cultivate “freedom” and a sense of home-made community rather than lead political revolutions. The act of “genderfucking” foregrounds much of the understandings of gender and sexuality that came out of the Athens music scene. Deliberately ambiguous (often shabby and secondhand) clothing drew obvious attention to gender as performative and costumery. A world of cats-eye glasses, prairie dresses, and wigs saturate the photography in the text, and gender and sexuality operate in the text less as the political categories of what Hale deems the “self-righteousness” of the 1960s and more of a “fuck it and let’s have fun” sentiment that encapsulated an irresolute approach to liberal politics. That’s not to say the distinctions of sexuality are disregarded. Ricky Wilson, an original founder of the B-52s, was openly gay in a Georgia public high school in the 1970s. In fact, Hale notes, his “coming out” was surprising not because he revealed his attraction to men (a foregone conclusion to most of his friend group), but because he used the word “gay” to describe it. Similarly, the specter of Ronald Reagan innately politicizes sexual practices as HIV/AIDS ripped holes in the fabric of the Athens and broader Georgia music scene (including Ricky Wilson, Benjamin Smoke, and Gregory Dean Smalley). Indeed, Hale ominously describes R.E.M’s 1984 “Little America” tour as a microcosm of the divides between “indie territory” in the United States and the surrounding areas that delivered an electoral college landslide to Reagan that same year.

Hale recognizes race as a point of conflict in the text. Certainly, a queer-of-color analysis of Georgia music might have examined queer Black artists coming out of Columbus and Macon, Georgia (such as Ma Rainey, Arthur Conley, and Little Richard). However, the focus on Athens specifically offers a unique line of inquiry into how racism still permeated through countercultural music movements not just in Athens, but also nationally. Notably, questions of privilege and “craft” loomed heavily over Black musicians, recording producers, and venue owners who recognized the higher standards that Black performers would be held to. Furthermore, Hale takes up the demographics of “colorblindness” that permeated alternate music and bohemian countercultures in Athens. Seeking to distinguish themselves from the openly hostile attitude towards Civil Rights that their parents held, white “alternative” communities believed simply refusing to talk about race was fundamentally antiracist and disengaged with political categorizations of race that had and continue to have tangible consequences for people of color living in the United States. However, the reverse proved true. “Colorblindness” manifested into a method by which white progressives could congratulate themselves on their liberalism and tolerance while simultaneously drawing few people of color into alternative music scenes.

From a crip scholar’s perspective, I longed for a slightly deeper analysis of HIV/AIDS and disability more broadly in the text. Disabled musicians like Vic Chesnutt are prominent actors, and HIV/AIDS-related complications ultimately killed Ricky Wilson, vastly changing the trajectory of the B-52s creative output and musical career. Similarly, the disease and federal mismanagement of it decimated the drag communities of New York and San Francisco and the “genderfuckers” who so influenced Jerry Ayers. Particularly considering that many of the subjects of the book and that many who knew them were queer, the role of HIV/AIDS as a quite literal eraser of oral history and memory seems like a noteworthy challenge for queer researchers, particularly those working in the Southeast.

Ultimately, Hale crafts a compelling narrative within complex categories of gender, sexuality, and the instability of place. As Georgia has found itself thrust into popular discourse about the shifting politics of the Southeast, its newfound status as a “purple state,” Hale’s attempt to navigate messiness of the great, glittering Oz of the Georgia Piedmont offers a unique and thorough investigation into the nature of art, culture building, and the sustaining power of the home-made in American counterculture.