Edward Onaci

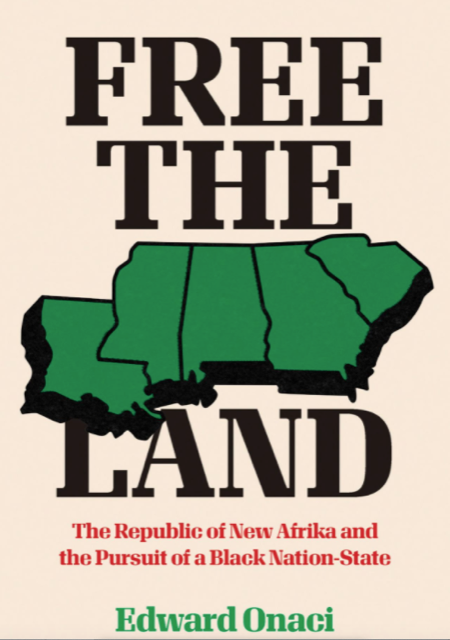

Free the Land: The Republic of New Afrika and the Pursuit of a Black Nation-State

The University of North Carolina Press, 2020

296 pages

$24.95

Reviewed by Christopher Ndubuizu

Edward Onaci’s Free the Land: The Republic of New Afrika and the Pursuit of a Black Nation-State presents the rich yet complex story of the Republic of New Afrika (RNA). In six well-articulated and researched chapters, Onaci chronologically walks readers through the sociopolitical circumstances that birthed the RNA to its destabilization. Drawing on a rich variety of sources including documentary evidence, participant observations, and interviews, Free the Land examines the RNA’s efforts to achieve self-determination through independent statehood and highlights the effects of this struggle on the lives of its members.

Throughout Chapter One, Onaci provides the historical context that resulted in the establishment of the RNA. Developed out of Detroit’s legacy of Black struggle throughout the twentieth century, the RNA was founded in Detroit by brothers Milton and Richard Henry who grew disillusioned about the idealization of integration. After organizations such as the Freedom Now Party and the Revolutionary Action Movement fought painstakingly to upend the racial violence and class exploitation disproportionately experienced by the Black poor and working class, the onset of the 1967 Detroit Riots acted as an impetus for the Henry brothers to embark the New Afrikan Independence Movement (NAIM), hence the RNA. Adopting Malcolm X’s and Queen Mother Moore’s philosophies on Black nationalism, NAIM argued that independent statehood, through land acquisition, was the most practical option for Black liberation and believed that Black people would never achieve liberation under the jurisdiction of the United States. To jumpstart the movement, the Henry Brothers who now changed their names to Obadeles, to indicate their Pan-Africanist identity, hosted the National Black Convention on March 30 and 31, 1968 where over 500 Black nationalists and Pan Africanist activists attended to declare their desire to establish an independent nation-state named the Republic of New Afrika.

Onaci transitions to articulate the purpose the Republic of New Afrika will serve in its mission towards Black liberation throughout Chapter Two. According to the Provisional Government of the RNA (PG-RNA), the RNA’s governing body, the independent statehood represented the highest form of self-determination and that level of self-determination could only truly become manifested through complete independence from the United States. Moreover, the RNA intended to become a Black socialist, independent nation that sought to end global imperialism, white supremacy, and capitalism through reparations, i.e., territorial acquisition. Therefore, the PG-RNA wished to acquire five southern states- Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina – because the region served as the historic homeland of enslaved African Americans. Onaci enlightens readers about the PG-RNA’s interrogation of the concept of United States citizenship and argued that African Americans were ‘paper citizens’ of the United States, in the sense that they were citizens on paper but never granted full protection under the United States law. Therefore, the PG-RNA classified African Americans as a nation held captive in the United States and listed in its declaration of independence document that ‘New Afrikans (citizens of the RNA) have a right to determine for themselves if they wish to take their consent of citizenship elsewhere.’ Onaci maintains that a New Afrikan designation was an inherently revolutionary political identity that operated on anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist, and Pan-Africanist principles. In its creed document (New Afrikan Creed), it states that New Afrikans have a personal commitment to act in service of nation-building and always be in pursuit of global liberation.

An intervention Onaci makes is highlighting the personal lives of New Afrikans. In Chapters Three and Four, readers are exposed to how New Afrikans applied the RNA’s ideologies to their personal lives, what Onaci classifies as ‘lifestyle politics.’ Resistance to cultural and political domination through name choices reveals one aspect of New Afrikan lifestyle politics. Throughout Chapter Three, Onaci focuses on how choosing a new name enabled New Afrikans the opportunity to exercise self-determination. Onaci reminds readers that names inherently have political meanings and the names New Afrikans gave themselves represented their politics which centered the pride in their African heritage and the decision to replace their slave names in favor of Afrikan ones. While many embraced Afrikan names to represent their political identity and their decolonial process even with a spelling of Africa which New Afrikans argue was originally spelled with a ‘K’, Onaci acknowledges the diversity of thought that existed within the RNA regarding name choices. Some New Afrikan chose to hold on to their birth names for legal and sentinel purposes and others concluded that assuming an Afrikan name was not necessary altogether. Readers are reminded that the adoption of a New Afrikan name was a personal process that involved internal exploration and years of careful consideration. Onaci transitions to discussing how the New Afrikans negotiated their work and family commitments as they embarked on a lifelong commitment to the struggle for liberation in Chapter Four. Onaci highlights educator Baba Hannibal who established and ran an independent African-centered school, called “Shule ya Watoto” that emphasized math and science. Hannibal believed that African people needed to become proficient in science and math for the sustainability of the RNA. Onaci presents a contrasting story of Bokeba Trice who was a City of Detroit employee but left the RNA after the birth of his first son and the concern that being a part of the RNA would threaten his employment with the city. Onaci concludes that how New Afrikans decided to live out the ideologies guiding their principles became an important site of tension and agency that allowed activists to begin exercising self-determination, even as they resisted the violence and domination of the American states.

Onaci explains how competing priorities, internal tensions, and state surveillance disrupted the RNA’s mission. Onaci specifically details how federal law enforcement agencies like the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), specifically its Counterintelligence Program, tracked and monitored the activities of New Afrikans to deter the RNA’s efforts to gain potential allies. Additionally, Onaci implicates the media’s complicity in portraying Black nationalists as criminals when violent encounters between New Afrikans and law enforcement were reported. The jailing of several key New Afrikans including the founder Imari Obadele drained the RNA of its much-needed human and economic resources to achieve its goals. Although RNA’s argument for territorial sovereignty and monetary reparations is nothing new, Onaci devotes the concluding chapter, Chapter Six, to highlighting RNA’s impact on the struggle for reparations. What made the RNA so unique was its attempt to remove land and people from the United States, not add to it, while simultaneously establishing agreements with Indigenous communities. The continuation of the struggle for reparations resulted in the creation of organizations such as the National Coalition of Black for Reparations in America in 1987, almost twenty years after RNA’s founding. The longstanding battle for reparations is illustrative of the Black freedom struggle which continues to this day with organizations such as the Movement for Black Lives.

Free the Land unequivocally falls under the canonical scholarship of Black Power Studies. A term coined by Dr. Peniel Joseph (2009), Black Power Studies uncovers the complex and often misunderstood history of the Black Power Movement because the Black Power Movement is often labeled as militant compared to the Civil Rights Movement which is regarded for its perceived respectability. Onaci asserts that traditional scholarship surrounding reparations rarely mentions the RNA’s unwavering role in securing monetary reparations. Onaci does the history of the RNA justice by offering a nuanced retelling of the organization’s history and its politics, specifically the politics of its members. Free the Land adds substance to the already rich yet complicated history of the Black Power Movement by centering RNA’s role in the struggle towards reparations and Black Liberation, a history that is arguably forgotten in traditional Black Power scholarship.

Though not explicitly stated by Onaci, the RNA’s desire to live in a society free from racist, capitalist and sexist oppression not only illustrates the act of radical imagination but also represents abolitionist ideals which are core principles commonly expressed in radical grassroots organizing spaces. Overall, Free the Land pays homage to long-standing radical, abolitionist movements.