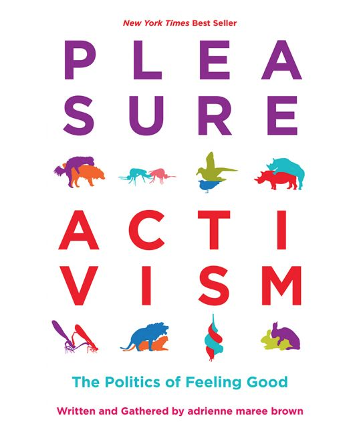

adrienne maree brown

Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good

AK Press, 2019

464 pages

$20.00

Reviewed by Keerti Arora

In Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good, adrienne maree brown curates a tapestry of essays, interviews, profiles, poems, images, and blog posts that orient readers to radical self-love and pleasure. One witnesses artists, scholars, and activists embodying a politics of feeling good. Her guiding question is, “Could we make justice and liberation the most pleasurable collective experiences we could have?” brown mostly draws from Black women’s accounts of their pursuit of pleasure amidst oppression, but also includes some voices that identify differently. She presents these pursuits not just as forms of resistance, but also as ways of living that provide avenues for liberation and self-expression. Her work moves and entices, leading readers to unlearn internalized oppression and practice community. Pleasure for brown is a guiding principle and a fundamental right. She refuses to settle for less and presents a montage of voices that show us how to do just that. The book gradually deprograms readers’ learnt tendencies of devaluing or stigmatizing their need for pleasure.

brown’s theorization of pleasure both continues the legacy of Audre Lorde’s “Uses of the Erotic” (1978) and broadens it to all aspects of life. Strikingly, for brown, pleasure is “not . . . a spoil of capitalism, [rather, it is] what our bodies, our human systems are structured for.” As Lorde does for the erotic, brown stresses that once one experiences the power and energy of pursuing and experiencing pleasure, there’s no going back. She makes intellectual, activism-related, and routine choices such that they become avenues for joy. She asks, “what would I be doing with my time and energy if I made decisions based on a feeling of deep, erotic, orgasmic yes?” Liberation, justice, and pleasure cannot be mutually exclusive, argues brown. Her privileging of feeling good within social justice work sounds counterintuitive at first. One wonders if pleasure can indeed guide practices that involve challenging hardened socio-political causes that perpetuate suffering. Herein she reminds readers of Tony Cade Bambara’s call to artists to make the revolution irresistible (Conversations with Tony Cade Bambara, 2017). Without discounting the validity of an embodied no, brown writes that fostering an embodied yes to the pursuit of pleasure energizes movements. Additionally, brown’s analytic is also informed by Joan Morgan’s theorization of pleasure politics in Black feminist thought as well as the latter’s work with the Pleasure Ninjas. Joan’s “Why We Get Off: Moving Towards a Black Feminist Politics of Pleasure” (2015), an essay that also appears in brown’s collection, repositions the master narrative of Black female sexuality from a site of historical trauma and intersecting oppressions to a site of agency, pleasure, and plurality. This shift resonates throughout brown’s work as well.

brown interacts as much as she educates and entertains. She divides her work into six sections that end with “hot and heavy homework.” These are exercises in rebuilding one’s relationship with pleasure that help one self-empower through self-exploration. The sections themselves are capacious; they cover experiential wisdom on the politics of feeling good, radical sex, radical drug use, and pleasure as political practice. Additionally, brown offers subsections such as skills for sex in the #MeToo era, self and collective healing, wholeness in movements, and liberated relationships. Together, these sections help one choose pleasure, radicalize sex education, deconstruct rape culture, work towards transformative justice, learn safe drug use in the context of harm reduction, and learn ways of healing trauma through pleasure. These conversations are presented within the larger framework of resisting racial, sexual and capitalist oppression.

All parts of brown’s text are affectively diverse. Academic essays alternate with conversations between brown, her friends, and her mentors. These conversations help one witness pleasure activism as praxis. She even includes a dialogue between herself and her sex toy in which the latter helps her learn her body’s capacity to feel pleasure. Section Two begins with Favianna Rodriguez’s images, designed to orient women to their sexuality and to the power of their own bodies (2012-2015). They offer a colorful, texturally different, and a simultaneously exciting and calming interspace. One of the most interesting moments in the text is brown’s toolkit for a pleasure activist wherein she describes her process of growing into her chosen kind of inclusive feminism: one that is imperfect, growing, and inclusive of all, irrespective of anyone’s chosen professional, gender, sexual expression or life choices. Additionally, she talks both about gender and identity fluidity and offers learning perspectives on self-love, orgasmic meditation, and self-pornography. In Pleasure Activism, one finds vulnerability, honesty, and roadmaps for healing. In presenting her personal journey towards self and sexual liberation, and mentoring through it, brown demystifies the tabooed and offers possibilities outside of known/familiar ways of being. Her lifelong experience of serving her community as a social justice facilitator, doula/healer, and pleasure activist enriches and expands the ambit of individuals (and their relationships with pleasure) presented. While Pleasure Activism may occasionally feel other-worldly for its references to alternative healing practices, it offers takeaway experiential wisdom for all. brown’s merging of creative endeavors and lived transformative experiences with scholarship generates a text that simultaneously empowers, educates, comforts, entertains, and most importantly, gives pleasure even as it informs one about it.