Sophie White

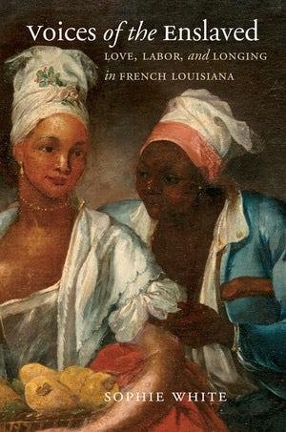

Voices of the Enslaved: Love, Labor, and Longing in French Louisiana

University of North Carolina Press, 2019

352 pages

$32.50

Reviewed by Gaila Sims

In Voices of the Enslaved: Love, Labor, and Longing in French Louisiana, Sophie White mines an archive unique to the French colony in order to learn more about the experience of slavery from the perspective of the enslaved. French court cases in the eighteenth century relied heavily on testimony, from defendants, witnesses, and victims, and French law also stipulated the careful documentation of this testimony. Unlike English colonies, where trial records were often published through commercial presses for the financial gain of their authors (who in some cases were officially involved as lawyers or judges), French courts required extensive written records of trial proceedings. These records were actually read out loud to those providing testimony, ensuring their approval of the transcription. Luckily for Sophie White (and her readers), many of these written records survive from the period of 1723 to 1769, allowing us a rare glimpse into the world of colonial Louisiana and the lives of those enslaved in the region. Organized by court cases, each chapter provides a window into labor, relationships, power dynamics, and gender roles in an area ever in flux, with individual enslaved people and their words at the forefront.

White begins her exploration with an extended note on method, appropriate given the richness of her sources and the imaginative approach she has chosen. While few enslaved people in French Louisiana were able to use the medium of the slave narrative to convey their stories, White argues that court testimony supplied an opportunity for enslaved people to share their perspectives, whether they were called to testify as defendants, witnesses, or even victims. While more than eighty trials involving enslaved people remain available through Louisiana archives, White focuses her attention on a handful of cases, placing the testimony of one or several enslaved people as the centerpiece of each eponymous chapter. Each section introduces the testimony from which White draws, first in English and then in French, before launching into the details of the case, the individuals involved, and finally the analysis of the testimony itself. White’s examination is highly effective, though occasionally meandering, as she shows how enslaved people took advantage of their time in court as the means by which they made themselves heard.

Chapter Two centers on Louison, attacked along with several other enslaved people by the French soldier Pierre Antoine Pochenet as they did laundry on the riverbank in front of the Ursuline Convent in New Orleans. Called to testify as the victim (a rarity for enslaved people at the time), Louison summarized the events of the assault alongside several other enslaved people who served as witnesses. White calls attention to the care with which Louison chose her words: identifying herself as a servant of the nuns, mentioning the clothing on her body, and referencing her piety in responding to the soldier’s demand that she kneel and ask his forgiveness. White uses each of these comments as an access point into larger discussions about the history of the Ursuline Convent, the status invoked by clothing worn by the enslaved, the class position of French soldiers, and enslaved religious affiliation. Through all of this contextualization, though, White retains Louison as the focal point, ensuring that the enslaved woman is given the time and space to explain the fateful encounter in her own words.

Chapters Three and Four delve into the topics of gender, motherhood, and interactions among the enslaved, attending to the story of Marie-Jeanne and Lisette in the former and Francisque, Démocrite, and Hector in the latter. Accused of infanticide, Marie-Jeanne, an African woman enslaved in the Illinois Country, was interrogated in New Orleans in 1748. Her accuser, Lisette, was a nine- or ten-year enslaved Ottawa girl with whom Marie-Jeanne had a contentious relationship. White uses the court case to explicate the nature of Black and Indigenous enslavement, parenting under the brutality of the slave system, and the economic contingencies of Black reproduction in eighteenth century Louisiana. While both Marie-Jeanne and Lisette disappear from the archive after the court proceedings, their testimony allows them both to speak about their experiences of life and labor in the French colony. For Démocrite and Hector, statements at the trial of Francisque permitted assertions of their prominence in their enslaved community, their responsibility for the safety and protection of their fellow slaves, and their enforcement of enslaved courtship rituals. A runaway from further North, Francisque appeared in New Orleans in 1766 and caused a commotion, performing at a dance, stealing eggs from some enslaved women, wearing flamboyant clothes and flaunting large bills. Accused of running away, theft, and property damage, Francisque employed his testimony as the means to share his travels and sophistication, while the men called as witnesses presented damning evidence of his failure to adhere to the rules of the world as they understood them. Francisque’s case shows both the diversity of slave experiences and the structure of the enslaved community of New Orleans in the late 1700s.

Voices of the Enslaved ends with the compelling love story of Kenet and Jean-Baptiste, enslaved on different plantations until their decision to run away to live together in 1767. White finds that the two met sometime in the 1740s and grew an attachment that they sustained over the course of fourteen years, culminating in their months-long stint as maroons at Chef Menteur. Kenet and Jean-Baptiste detail their time as fugitives, accounting for their escape, the assistance they received from other Black folks and nearby Native tribal members, and the domestic arrangement they adhered to during their time together. While White’s analysis of the enslaved people she studies sometimes errs to the impersonal, for Kenet and Jean-Baptiste she summons an abundance of empathy and care, inviting her readers to feel their fear and determination along with her. Along with Louison, this chapter offers the most emotionally compelling account of enslaved life in French Louisiana, and Kenet and Jean-Baptiste will stick with readers long after the book’s end.

Adorned with an abundance of color images, maps, diagrams, and objects, Sophie White’s Voices of the Enslaved offers a unique and captivating exploration of the experiences of enslaved people at a time period that produced few firsthand accounts of their stories. For those interested in the history of slavery, race and gender, and the colonial period, this study offers enslaved people a chance to speak for themselves through the medium of the archive, chronicling their lives, memories, relationships, and understanding of their place in the world. Readers will be grateful for their introduction to Louison, Marie-Jeanne, Lisette, Francisque, Démocrite, Hector, Kenet, and Jean-Baptiste and for the glimpse into their world.