Tina Campt

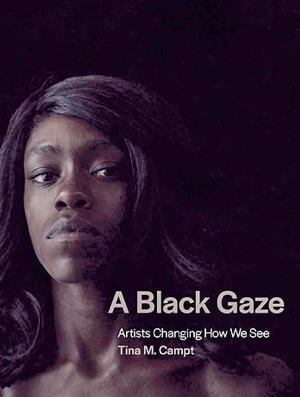

A Black Gaze: Artists Changing How We See

MIT Press, 2021

232 pages

$24.95

Reviewed by Holly Genovese

In A Black Gaze: Artists Changing How We See, Tina Campt explores Black artists working across mediums to expand and shift the notion of “The Black Gaze” to “A Black Gaze.” This seemingly small change signifies the multiplicity and movement inherent to A Black Gaze. Campt argues that A Black Gaze is seen in modalities outside of film, its traditional medium. Movement is inherent to Campt’s analysis of Black Gaze. Campt writes “it is at once a critical framework, a reading apparatus, a term that describes an artist’s practice, and a spectatorial mediation that demands particularly active modes of watching, listening, and witnessing.” Rather than a single unified gaze, A Black Gaze is always moving and “sets in motion a choreography of practices that are constantly up for grabs”. Campt often writes in first person, narrating her own encounter with the artworks she visits, the weather, and the physical relationship between herself and the artist’s space.

Arranged in Verses rather than chapters, Campt emphasizes the engagement of all senses when experiencing visual culture. How does one listen to a visual or feel music? In many ways Campt brings some methods of knowing black music to black visual culture here. Campt’s A Black Gaze both structurally and theoretically expands, moves, and creates space for a new way of looking while focusing on an artist per verse: Deana Lawson, Kahlil Joseph, Arthur Jafa, Simone Leigh, and Luke Willis Thompson. Building on the work of Black feminist film theorists, Campt engages with and extends canonical definitions of the Gaze. Rejecting Laura Mulvey’s dichotomous assertion that the white male viewer is the “bearer of the look” and that white women are “an object to be looked at,” she relies and expands on bell hooks’s work on the oppositional gaze. For hooks, the gaze is always already political and is directly linked to the long history of the policing of Black people’s “looks.” A Black Gaze, for Campt, builds on hooks’s theory but rejects the idea of the objectified person “to be looked at” and instead argues that it is an encounter. A gaze rather than “the gaze” implies multiplicity, movement, and varying mediums. Campt isn’t rejecting hooks but rather building on her work, multiplying it, and varying the modalities in which it can be read and heard.

Each verse is about an encounter with an artist. The first is Deana Lawson, who intersperses family-oriented images with nudes in her photographic work. For Campt, “Lawson creates intimate, yet uncomfortable relationships by twinning the respectable with the profane and celebrating the dialogue between them.” For Campt, sitting on the floor of the gallery writing is her way of dialoguing with the art, writing at and towards it physically as well as intellectually.

The second verse begins with a meditation on the weather, as Campt travels to see artist Kahlil Joseph (director of Beyoncé’s Lemonade) in Los Angeles. Here, Campt reflects on the way the weather shapes her experiences with artwork and how this mirrors reflections of Christina Sharpe. Campt moves beyond a simple exploration of Sharpe’s concept of the ‘wake’ and instead reflects that “For Christina Sharpe, the weather is a powerful metaphor for understanding the atmospheric relations that structure the lives of Black folks.” Here, during her exploration of Joseph’s films and the Black quotidian, we get her central argument that “Black contemporary artists are creating new ways of visualizing Black struggle and transcendence. In doing so, they offer a different trajectory for Black sociality, i.e. the practice of fabulation rendered not through narrative or narration, but through the Black body itself and its extraordinary capacity to manifest something I call Black counter gravity. Black counter gravity defies the physics of anti-blackness that has historically exerted a negative force aimed at expunging Black life.”

Verse Three centers Arthur Jafa and “visual frequency,” where Campt truly delves into listening to visuals and to silence. For Campt, “frequency is at once temporal (a recurrence or repetition over time in intervals), sonic (it registers as sound and through pitch), kinetic (it is constituted by movement in the form of vibrations that occur at a range of velocities and intensities, haptic (it is a form of contact that registers in embodied forms through our encounters with objects outside of ourselves) and visual (a spectrum ranging from the visible to the invisible that triggers individuals responses).” Jafa wanted to make the visual inspire the feeling often associated solely with Black music. Jafa’s films in particular explore an ethics of care among Black women and a type of domestic imagery that is often uncomfortable for the viewer.

In Verse Five, Campt writes of this as hapticity, a way of engaging. Here, Campt asks, “Can we listen to images?” and the ways in which she is shifting engagement with the senses becomes clear: she writes “sound is only audible in relation to quiet.” In Verse Five, Campt focuses on multimedia artist Simone Leigh and her work the “loophole of retreat” a reference to Harriet Jacobs, at once fugitive and in danger. Campt writes “the loophole of retreat is a place Jacobs claimed as simultaneously an enclosure and a space for enacting practices of freedom—practices of thinking, plotting, envisioning, and realizing alternative forms of possibility.” Again, Campt emphasizes the work’s focus on Black women’s care work and labor.

Verse Six focuses on Luke Willis Thompson and in particular his work autoportrait, an artwork somewhere between still image and film. The focus is on anti-black violence, on the murder of a Black man, and Campt says that what makes autoportrait distinct is the “adjacency to rather than identity with forms of anti-Black violence his piece so poignantly evokes.” Here we come the closest to a singular definition of a Black Gaze by Campt as she writes “a Black gaze does not describe the viewpoint of Black people. It is not a gaze restricted to or defined by race or phenotype. It is a viewing practice and a structure of witnessing that reckons with the precarious state of Black life in the twenty-first century.”

By narrating her own encounters with these artworks: the weather, her meals and travels and the way she sat or stood and engaged the work, we see Campt’s own “structure of witnessing.” Her book enacts A Black Gaze, multiple modalities, and formal innovation while also witnessing the quiet work of these artists.