Hiʻlei Julia Kawehipuaakahaopulani Hobart

Cooling the Tropics: Ice, Indigeneity, and Hawaiian Refreshment

Duke University Press, 2023

249 pages

$26.95

Reviewed by isaac dwyer

Within the paradigm of the global refrigeration chain, how did the taste for ice develop in Hawaiʻi? What does the aesthetic of industrial thermal technologies in the Pacific archipelago reveal about the specificities of haole (id est, white settler) settler colonialism and Kānaka Maoli resistance?

In Dr. Hiʻlei Julia Kawehipuaakahaopulani Hobart’s new monograph, Cooling the Tropics, the new faculty member of the Program in Ethnicity, Race and Migration at Yale University argues that nigh all cold thermalities in Hawaiʻi, from consumable pleasures to the state management of volcanic alpine tundra, become semiotically articulated in what the I-Kiribati poet Teresia Teaiwa dubbed the ‘militouristic.’ Employing self-reflective ethnographic and historiographical research methods and anthropological theory, Hobart traces the past two-and-a-half centuries of Hawaiʻi’s cold under colonial occupation through five expressions: cocktails, refrigeration, ice cream, Hawaiian ice shave, and Mauna Kea.

Hobart’s critical lens emanates from her expertise as a food scholar. By considering the genealogy of the islands’ fruity makai-side resort cocktails and their turbulent relationship with the transoceanic ice trade, Hobart shows how a taste for their boozy sweetness was produced by the haole plantation overseer class as leisurely respite from equatorial torpor. While white consumption of chilled cocktails was permitted and licensed by the Hawaiian government, the 1850 penal code declared any native found imbibing the same would be summarily fined. In contrast to the logic of sexually racialized notions of inborn indigenous lassitude, whites were permitted to not only indulge in the mixological, but profit from it handsomely. “This trick,” Hobart writes, “in which alcohol polarized haole leisure and Hawaiian languor, reverberated throughout tourist industry stereotypes that, into the twentieth century, celebrated white comfort and expense of Native labor.” Hobart’s intervention thus trods along a similar path as Sidney Mintz’s landmark 1985 study of the sugar industry, Sweetness and Power.

The aesthetic of cold consumption is further framed vis-a-vis its utility for systematic indigenous dispossession by the ice shave. Through close readings of advertisements, attending to the psychoanalytical substrate of commercial marketing, Hobart argues that ice shave is leveraged as a saccharine sublimation of Hawaiʻi’s racial politics. The bouquets of tropical syrups ooze oh-so-gently into one another—maintaining their distinct colors yet suspended in whiteness. Each color is imagined as a distinct race suspended in mellifluous concert, offering a “metaphor […] wherein a sugar plantation economy produced a racially harmonious society for the only US state with a nonwhite majority population.” To proffer the sweet rainbow as epitomizing the islands’ “local flavor” leads to “Hawaiianness [becoming] obliquely depoliticized in the service of neutralizing Kanaka Maoli indigeneity.” To render indigeneity neuter through visual subsumption, Hobart argues, is de rigueur in the capitalist packaging of “local flavor.”

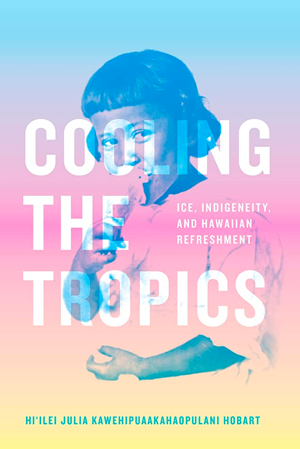

The most delectable elements of Hobart’s work are to be found in her close readings of visual advertising materials. Examining a 1921 advertisement for Rawley’s ice cream, Hobart presents us with the image adorning the cover of her book, a full-page portrait of a young Hawaiian girl:

Presented without title or logo, it trades the purity of nature for the purifying embrace of civility. Instead of flowing freely, her hair is styled with glossy bangs and short curls that show off the nape of her neck. Rather than depicted in an outdoor setting, she is posed for a formal studio portrait, sitting with her torso turned toward the camera to create a three-quarter profile, left hand resting in her lap.

The image offers a study in contrasts: the girl’s brown skin gleams against a white pinafore. She is smiling, but her lips are obscured by an ice cream cone that sets off her brownness with its milky whiteness.

Hobart offers the image along with a self-condemning advertising byline from the Christmas edition of the tourist periodical, Paradise of the Pacific. It provides a lesson on the prosody of orientalist pederosis:

Merry Christmas. Santa Claus doesn’t forget good little girls just because they live in Hawaiʻi, where the old fellow’s reindeer outfit would have a pretty hard time sledding, and nary chimney exists for his convenience. Nevertheless, as one may easily perceive, he manages to deliver the goods. This child is pure Hawaiian, and furnishes a beautiful example of what Hawaiian eyes can do.

Hobart hardly needs to go in for the kill, but she does so exactingly: “While it is unclear exactly what her eyes are able to do in this instance (Entice a pedophilic onlooker? Convince a skeptical Santa of her humanity?), the trappings of whiteness become materially and metaphorically significant to purity’s embodiment.” Hobart’s critique is like that of an anticolonial Edward Bernays, revealing the frozen white dairy dessert lapped up by Kanaka child like some kind of eugenic eucharist.

Food scholarship and critical geography collide as Hobart turns her gaze towards the internationalized galaxy-gazing megaplex scooped into the Mauna Kea summit. No aspect of the occupation’s imperial kitsch is spared: from the flourishing fun park activities, Exempli gratia: photos of a Haole skier hittin’ the slopes backgrounded by telescopes, captioned “Hawaii Not?” and NASA astronauts-in-training putzing about in full moonwalk gear through what the federal agency Columbused as “Apollo Valley.” Hobart’s critical intervention, however, gains its strength not only from its astute analyses of the US militaristic occupational apparati, but her firm argumentation for the specificities of indigenous sovereignty, futurity, and relationality.

Mauna Kea, the islands’ highest volcano, is the site of the world’s most important and sophisticated astronomy observatories. It is also the center of the Kānaka Maoli weltanschauung; its caldera the piko (navel) from which the world and our known reality emerged. As the preparation for construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT)—a new telescope of gargantuan extent, as its name would suggest—came to a head in 2015, the summit access road became a site of strategic occupation by Kānaka Maoli activists and their allies, to protect their sacred site from further imperial desecration. Hobart’s research draws on the archives to historicize the logic of the astronomical incursion: “the summit of Maunakea has been systematically recast as a space both otherworldly and a-national […] research sites like Maunakea often become valued as places that transcend international politics […] belonging to no one in particular and to everyone in general.”

It is Hobart’s exploration of her personal participation in the occupation of the summit protesting the TMT that provides the material fodder for her final theoretical intervention. Volunteering as a part of the culinary crew, part of her kuleana(responsibility) was the thermal management of donated perishables, entailing constant monitoring of the ice blocks rapidly melting in the high-altitude sunlight. Arising from the same semiotic logic undergirding her close-readings, Hobart proposes we consider this ice melt through the lens of “not only […] anticolonial struggle but also […] interdependence and calibration: a phase state change that […] re-forms bonds at a molecular level. For Indigenous archipelagic peoples, melt can remind us of shared struggles across vast geographies.” This could be construed as an over-imaginative leap. Does not the threat of the deteriorating thermal technology—that is, a melting ice chest filled with shredded meat straight off a container ship—reveal a fundamental vulnerability? Perhaps, but such a bold leap might be necessary to traverse the crevasse from critique towards liberatory manifesto.