Orrin Pilkey, Norma Longo, William Neal, Nelson Rangel- Buitrago, Keith Pilkey, and Hannah Hayes

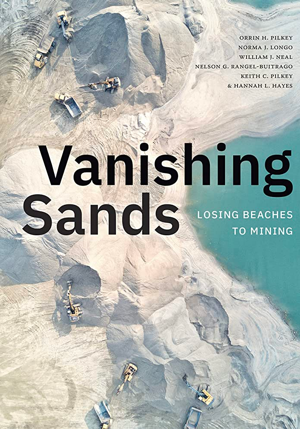

Vanishing Sands: Losing Beaches to Mining

Duke University Press, 2022

248 pages

$25.95

Reviewed by Henrik Jaron Schneider

Vanishing Sands: Losing Beaches to Mining (2022) is a critical interdisciplinary and transnational project centered on the devastating global environmental and social impacts of sand mining in the late twentieth and early twenty- first centuries. By bringing together geology, geography, law, and the histories of land rights and extractivism, the six authors of Vanishing Sands take the reader on a journey through the world’s sand mines, highlighting the ways in which this frequently un- and underregulated form of resource extraction is destroying our beaches, coastal ecosystems, and even cultural heritage.

In addition to arguing that beach and river mining is one of the main reasons for on- and offshore erosion and the destruction of coastal communities, this book is a plea for the protection of our beaches and a call for action to find more sustainable alternatives to sand. The ever increasing demand for aggregates that constitute the foundation of large-scale construction sites across the globe is concomitant with the unequal distribution of environmental degradation, coastal erosion, and corruption accompanying the type of extractivism integral to Vanishing Sands.

The multidisciplinary team of authors employs a plethora of primary and secondary sources as well as personal anecdotes for their critical discourse analysis of sand extraction. Vanishing Sands draws from geological data, quantitative socio-geographical work, and research on coastal transformations to bring together the histories of our rivers and beaches, global capitalism, and environmental injustice. Moreover, legal documents highlight the ambiguous nature of sand mining regulations in selected countries in Asia, Africa, and the Americas. In doing so, the authors emphasize a sense of urgency, which they further stress by including activist sources like D. Delestrac’s 2013 documentary Sand Wars and the call for ‘Sand Rights,’ a legal framework spearheaded by law specialist K. E. Stone in 1999.

Similar to T. Mitchell’s Carbon Democracy (2011) and A. Needham’s Power Lines (2014), where the authors follow oil and coal in their analysis, respectively, Vanishing Sands tracks the movement of sand to explore the resource’s relationship with natural and built environments. Existing research, such as D. Padmalal and K. Maya’s Sand Mining: Environmental Impacts and Selected Case Studies (2014), provide a comprehensive overview of the environmental impacts of sand mining through in-depth analyses of case studies world-wide. While Vanishing Sands also addresses the environmental degradation of nature, the book adds to preceding literature a frequent focus on the social and cultural implications of aggregate extraction. In ten chapters, Vanishing Sands moves from sand’s physical properties to organized crime and legal forms of sand extraction, concluding with a discussion on possible mitigations for diverse forms of violence caused by sand mining.

Chapters One and Two introduce the material at the center of Vanishing Sands. Ironically, despite being a metaphor for inexhaustible abundance, the first chapter argues that the type of sand used for industrial purposes is a limited resource. Moreover, it outlines the stakes and

guiding questions of the book: Who mines sand? Why do we mine sand? Where does sand mining occur? What are the effects of sand extraction on the environment and coastal communities? And lastly, why should beaches be protected? Chapter Two discusses sand’s properties, arguing, “Sand [emphasis in original] is a size term, independent of mineralogy or shape.” Thus, sand’s diverse characteristics inform its use as a concrete aggregate, for landfills, artificial islands, beach nourishment, and fracking, to name a few.

Chapter Three focuses on Singapore’s “insatiable sand appetite,” suggesting that the city-state’s extensive land reclamation projects fuel unregulated sand extraction in Southeast Asia. Acclaimed as one of the world’s greenest cities, Vanishing Sands intervenes in this assumption by arguing that through Singapore’s various layers of contractors, it obfuscates its complicity in the environmental destruction and violence caused by sand extraction in Southeast Asia.

In “The Sands of Crime,” Vanishing Sand departs most clearly from preceding works on sand mining by dedicating a whole chapter to the mafia-like structures of sand robbing in the Maghreb, Sub-Sahara Africa, India, Southeast Asia, and the Americas. This chapter calls for changing regulations and the implementation of economic incentives to provide sustainable alternatives for social groups whose livelihoods depend on illegal sand extraction. A list of violent events connected to sand mining in the appendix complements Chapter Four and highlights the intensity and global scale of violence associated with aggregate extraction.

Chapter Five investigates the impact of dams and sand mining in rivers on beach erosion. In doing so, the authors of Vanishing Sands introduce the critical intersection of river engineering and epidemiology, calling for more research on the relationship between stagnant water and virus outbreaks, such as the 2018 Nipah virus outbreak in Kerala, India. Reversely, this chapter also describes the positive ecological effects attributable to dam removal projects in Washington.

“Barbuda and Other Islands” explores sand extraction in predominately tourism-centered economies and argues that the harmful impacts of sand mining are a governance issue. As a solution, Vanishing Sands proposes a diversification of the Caribbean islands’ economies to provide more opportunities for communities dependent on tourism. In Grenada, Chapter Six explains, coastal erosion caused by extensive sand mining washes away archeological sites and graveyards. Thus, this chapter also offers a critical impulse for future research on the relationship between knowledge production and sand extraction.

While Chapter Seven provides additional case studies for unregulated sand mining and urges politicians to protect the shorelines of South America, Chapter Eight probes more regulated forms of sand extraction by looking at beach nourishment projects in the US. Nonetheless, Vanishing Sands still argues that while legal, this form of sand mining still degrades the environment and is not sustainable in maintaining our beaches’ protection. Moreover, this chapter discusses current debates to import sand from the Bahamas to nourish the shorelines of Florida, thus mirroring approaches reminiscent of those employed by Singapore (Chapter Three). Ultimately, Chapter Eight calls for a redirection of money used for beach nourishment projects in favor of “moving buildings back from the beach” in America’s coastal communities.

Chapters Nine and Ten shift the focus more explicitly to solutions for sand mining on beaches and in rivers. Chapter Nine offers a set of case studies in Africa, arguing that despite the continent’s vast deserts, the disastrous effects of unregulated sand extraction from rivers and beaches, which leads to collapsing buildings, flash floods, and violent crime, still plague countries such as Morocco, Mozambique, and Sierra Leone. Chapter Ten picks up on the “aggregate sand paradox” that desert sands aren’t suitable for concrete production and calls for a reconsideration of such aggregates as a more sustainable resource. In addition to moving landward for the sake of beach protection, Vanishing Sands concludes with an urgent call to funnel resources to develop and locate inexpensive alternatives for beach and river sands.

Ultimately, Vanishing Sands is a rich collection of the diverse intersection between sand mining and its detrimental effects on society and the environment. It provides numerous impulses for further research on various academic fields’ relationship with sand extraction, such as epidemiology, environmental history, archeology, and law, to name a few. Thus, Vanishing Sand is a critical read for anyone who engages in the interdisciplinary and transnational research of our planet’s coasts and cares about the protection of our beaches.