Estella Gonzalez

Chola Salvation

Arte Público Press, 2021

208 pages

$18.95

Reviewed by Isabel Ibáñez de la Calle

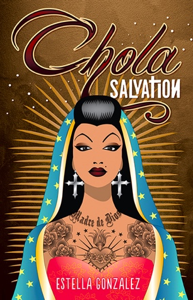

With a very cool-looking illustration of La Virgen de Guadalupe with purple lips and tattoos on her neck on its cover, the book Chola Salvationpromises to be bold and exciting. The 16 short stories written by the Chicana author Estella Gonzalez confront us with social inequalities, poverty, cultural background, and family relationships that Mexican Americans and immigrants experienced during the eighties in East Los Angeles. In this neighborhood, the author was born. One of the short stories’ most exciting parts is how many characters deal with the stereotypes placed on them by the hegemonic discourses, the language boundaries, and the difficulties people crossing the border face when circumstances are most vulnerable. The author tells these stories without essentializing or victimizing working-class people full of contradictions, dreams, and sometimes violence. The way Gonzalez uses language is also compelling: she includes Mexican and American slang and incorporates a fresh style that makes these stories truly enjoyable.

The story that gives the name to the entire collection is the most complex of all. It begins when Isabela is alone in her parent’s restaurant located in East LA. Without knowing if it is a dream or a supernatural appearance, the Virgin of Guadalupe and Frida Kahlo enter the establishment and order a drink. She has to take a second look as they are not the typical images she has seen since she was a child. The only way to recognize these two iconic figures of Mexican culture is by their unibrow and the halo of holiness that contrasts with the flannel shirt and purple-lined lips of the Virgin. Yes, Frida and Lupe are two cholas, like some girls from the neighborhood Isabela admires. Both come from beyond to give her a series of “new rules” for survival before she turns fifteen. These mandamientos are essential to escape patriarchal domination that, in her case, is revealed through sexual abuse.

What seems to be a cliche that plays with two of the most used images in Mexican American narratives gradually becomes a complex story of incest and maternal silence that conceals desires and violence. In just 28 pages, the author presents us with a story of resistance that can only come from a community of women. But this is not the only example of how to tell complex stories of migration and social inequality in a few pages. On “St. Patrick’s Day,” Gonzalez tells the story of a Mexican immigrant from Guadalajara that dreams of saving money to return to his homeland. In LA, he gets involved in a relationship with a woman with a daughter he has adopted and adores. The girl claims to be American, so he realizes it would be difficult for her to adapt to Mexico. Coming back seems more and more impossible as time passes. This is an experience many migrants have with the passing of years. Every story has an insightful way of looking at moments in people’s lives that we usually don’t see on TV or in mass media. At the same time, these stories represent many past experiences Mexican Americans and Latinx communities have faced and continue dealing with these days. Gonzalez shows it is possible to write problematic themes comedically and entertainingly.