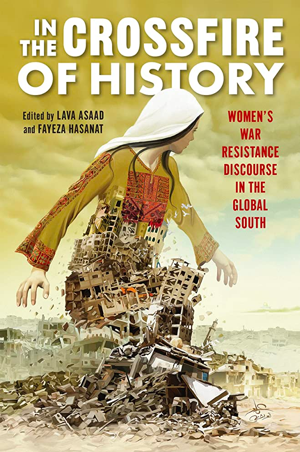

Lava Asaad and Fayeza Hasanat, eds.

In the Crossfire of History: Women’s War Resistance Discourse in the Global South

Rutgers University Press, 2022

214 pages

$29.95

Reviewed by Haneul Lee

Western-oriented feminist literature has claimed to have an all-around capability to analyze and decipher the meaning of resistance by women. However, it has failed to capture varied scales of crises and their impact on women of the Global South. That often results in romanticizing their fights for social transformation. As a minoritarian intervention to the existing feminist discourse, In the Crossfire of History: Women’s War ResistanceDiscourse in the Global South, a collection of essays edited by Lava Asaad and Fayeza Hasanat, critically reframes women’s struggles and resistance performed in the Global South from an insider and intersectional angle.

This collection traces the female bodies in resistance beyond their agony, highlighting that what they fight against is more than gender justice. Selected essays introduce a wide range of “alternative and creative practice of resistance” performed by women of the Global South. The compelling case studies tell us how a new narrative of resistance can be constructed in art and media, literary texts, and a larger social space for activism and advocacy.

Part one of this collection focuses on the visual representation of women’s resistance in prison art in Syria, nationalist war films in Bangladesh, and a Western-produced documentary about Kurdish female fighters. Stefanie Sevcik examines how imprisoned Syrian women use photography, painting, etching, and crafts to represent their bodies and emotions “melting” in a prison cell, isolated from the public and domestic spaces. The prison artists’ self-portraits of enervate facial expressions and body postures represent the bodies as sites of ongoing structural and physical violence under the Syrian justice system. Such a visually disturbing

memoir of isolation and dehumanization could be seen as a form of resistance to a personal feeling of being forgotten—what she calls “creative insurgency.” In subsequent essays, Farzana Akhter and Lava Asaad examine how women’s bodies have been portrayed in films. If an image of the female body has been exploited as a symbolic object for supporting an allegory of national rebuilding in the post-liberation war Bangladesh films, the Kurdish women’s bodies have been made merely “sensational” in Western documentaries, which is “myopic and orientalist.” However, there are intricately mingled desires under their armed resistance to embody their social roles, which are not limited to the masculinized female fighters but extend to mothers, daughters, and friends in the community.

The book’s second part focuses on the fictional representation of women-centric memoirs by female writers from Argentina, Palestine, India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, displaying the absurdity of war violence or displacement. Lucia García-Santana discusses how a female political consciousness can be constituted by closely analyzing female characters and their shared struggle in an Argentinian fictional work about the Dirty War (1974-1983). Indeed, the female characters’ sharing of their war experiences makes them a “collective self” instead of isolated individuals. Doaa Omran asserts in her essay on Arab women writers about Palestinian memoirs that their imagination functions as an “archive” of underrecognized micro-historical details about a shared lived experience that women underwent in detention camps or on borders. In her analysis of the identity formation of South Asian women in Partition literature, Margaret Hageman also states explicitly that such an auto-ethnographical reproduction of personal memories further intends to speak for and decolonize South Asian women caught in the ambiguous third space physically and emotionally. Carolyn Ownbey’s essay alsoexamines the implication of representing border women in India at the Partition. For her, writing about the women suppressed by law and religious precepts is a gesture of feminist care that builds solidarity between the border women and the writer and participates in recovering their voices. Compared to the aforementioned essays, Moumin Quazi’s work is a deep dive into a dark matter—the fictional representation of the suicide of Sri Lankan women as a form of resistance to the aftermath of war. The trope of inversion in fiction avoids framing a female body as a mere victim-survivor. Rather, it shows that the female body turns into a paradoxical site where the absurd war violence and its consequences are finally exposed in the process of performing self-destruction.

Essays in the last part of the book broaden its scope to the emergence of grassroots political activism and advocacy in college classrooms. The traumatic memories of women during wartime reproduced in written works are often taught in colleges in Bangladesh. Shafinur Nahar’s survey shows that the materialized disturbing memoirs of women forgotten from the victorious national history can work to transform the classroom into one where the affective memory of female war survivors can be intergenerational. If not in the classroom, organizing a community might be one of the most important tactics for the feminist movement to support fellow members in staying connected. Yet, Nyla Ali Khan argues in her essay that grassroots activism should be intersectional by looking for a way to collaborate with other organizations. In this way, feminist activists can build a more extensive social space for women in Kashmiri and use that space as a radical care community. Matthew Spencer’s chapter discusses the intersectional feminist movement in the global context. The growing of transnational ecofeminist movements across different countries shows beyond doubt the possibility of building “solidarity networks” to force material change on the ground.

However, although this collection successfully captures the unexplored forms of resistance of women of the Global South, readers can be skeptical about how the narrative of decolonization of the colonized female bodies are delineated in the selected essays. Their writings of the micro-scaled resistance of women are being reiterated under traditional academic writing conventions rather than under creative and insurgent writing practices. Perhaps the overdependence on Western feminist theories in film and media studies could be another factor in deferring to decolonizing a method of reading women and their struggles and resistances in visual media and art. Particularly in Chapter Two, using Laura Mulvey’s gaze theory to analyze women’s bodies in Bangladesh war films is seemingly helpful. However, the film analysis falls slightly into reiterating the Western-oriented analytical angle, making it challenging to decolonize and look critically at the given oppressions.

Yet the conversations offered by In the Crossfire of History: Women’s War Resistance Discourse in the Global South are still compelling because they serve as stepping stones for continuing the discussion about women of the Global South and what they fight for—and how. In that sense, the book’s virtue is in deconstructing the dominant view on women and their resistance and radicalizing the way of understanding the politics of women’s struggle and resistance to power as performed in the Global South context. The collective efforts made through this collection suggest an alternative angle for what marginalizes women of the Global South and give a new vantage point for viewing women’s problems to readers seeking a way to decolonize not only marginalized women of color but also the global feminist discourse.