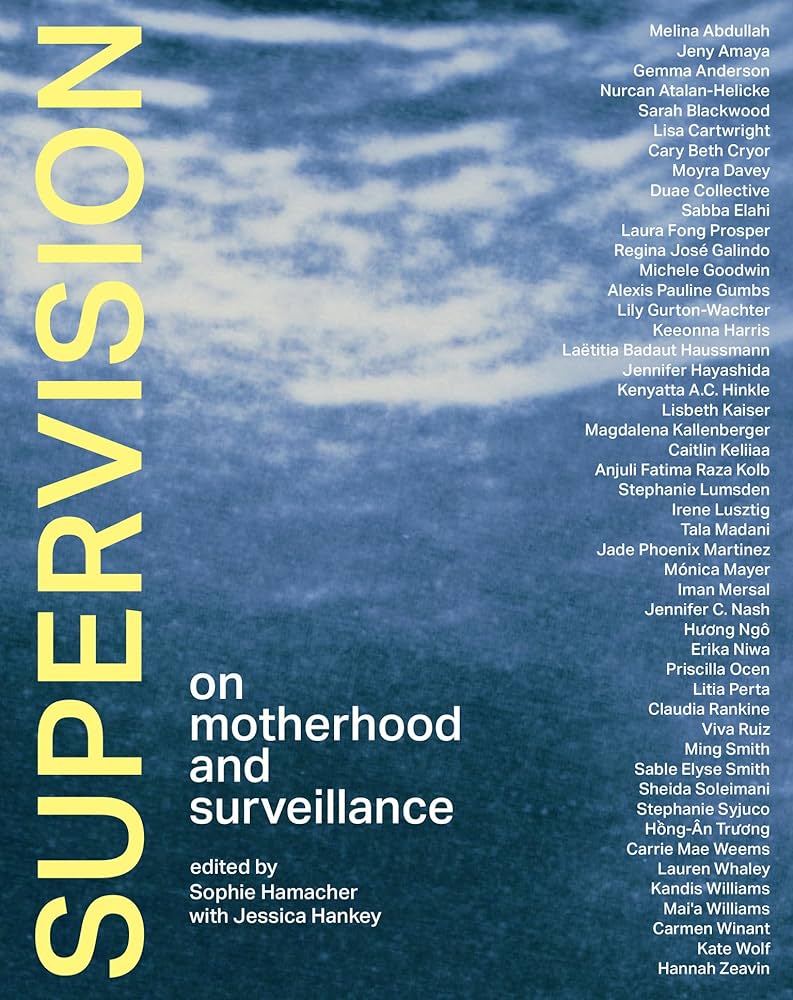

Sophie Hamacher with Jessica Hankey, eds.

Supervision: On Motherhood and Surveillance

The MIT Press, 2023

200 pages

$35.00

Reviewed by Courtney Welu

In a two-page spread, an art piece by Carmen Winant entitled My Birth showcases images of the physical process of many different mothers in labor. Not only do we see their naked bodies portrayed on camera, but we see the crowns of babies’ heads exiting their bodies, their newborns latching onto their nipples, and other increasingly intimate and vulnerable moments captured on film. Why is the camera there? What is its purpose? Are the women aware that they are being photographed?

In Supervision: On Motherhood and Surveillance, Sophie Hamacher, Jessica Hankey, and their collaborators question how we define both motherhood and surveillance in light of the other. Mothers surveil their children while their “behaviors and bodies are observed, made public, exposed, scrutinized, and policed like never before.” Using a wide variety of media, including interviews, personal essays, academic essays, poetry, and visual art, the book manifests the intense labor that goes into the act of (pro)creation. The women who contributed to the collection actively engage in both of those processes at the same time.

Hamacher is the primary editor of the collection and takes on a far more visible role than is typical for collection editors. Not only does she include her own visual art pieces—including film stills that she took during the first six months of her daughter’s life—but she also interviews many of the book’s collaborators about their own experiences of academic and artistic spaces as mothers whose bodies are under scrutiny. Hamacher writes in the preface that she began this project after her “vision changed” when she became a mother. Not only was she attuned to constantly watching her daughter, but she also underwent “an unmistakable shift in [her] artistic production” where her child had to be her primary focus rather than her camera. In this new state of motherhood, she became aware of how she was being surveilled as well by “advertisers, medical professionals, government entities, people on the street.” The relationship between how she was watching and how she was watched was the impetus to speak to other mothers about their experience of surveillance.

The interviews allow researchers and artists to take a casual tone with Hamacher as they discuss their work, and Hamacher is able to thematically tie together the subjects she is most interested in. One of her focuses is the changing technologies that mothers and other caregivers use to watch their children, especially the baby monitor. “So because you can surveil, should you?” Lisbeth Kaiser, children’s book editor, asks as she reflects on how parenting has changed between her generation and her parents’, as the technology of baby monitors and nanny cams are now so prevalent. In the same interview, Dr. Erika Niwa adds that when she was pregnant, doctors could not determine the gender far in advance of the birth, and 3-D ultrasounds were only just beginning.

The change in technology is not just generational, however; it is also split across racial and class lines. In her essay “Policing the Womb,” Michelle Goodwin reflects on how many technological advancements do not benefit poor mothers or Black mothers. For rich white women, “reproductive privacy and freedom are tangible concepts in uninterrupted operation,” as they can access a wide range of reproductive options while Black women and women living in poverty are often criminalized during their pregnancies.

The book is deeply attuned to the differences in how different types of mothers are surveilled, especially stressing that the police state is far more invested in surveilling Black mothers who also suffer from much higher maternal mortality rates than white women. Black feminist activist Keeonna Harris talks about how she was surveilled as a Black teen mother and how social surveillance from other mothers and community members is an extension of the state’s surveillance. “We don’t just wake up with these thoughts and these fears,” she explains to Hamacher. “It is bigger than us. It is the state using random people to do their job, to be Big Brother, and it wants us to police one another.” The reflections that Harris and other Black mothers provide allow readers to think through the implications that there is not a universal experience of motherhood, even if there are commonalities.

Other writers explore these fraught dynamics through poetry and art; one of the most effective is Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s poem “Heavy Swimmers,” written for Ebony Wilkerson, “a black mother who drove herself / and her children into the Atlantic Ocean / saying she was taking them all to a better place.” Wilkerson and her children survived this encounter, which resulted in Wilkerson’s incarceration. Gumbs’s deep empathy for Wilkerson’s struggle as a mentally ill Black mother in a society that did not offer her any meaningful help stresses the kinship and connections that are implicit in the creation of the collection.

Hamacher is concerned with whether surveillance is inherently negative; she receives some pushback from her interviewees on the equivalencies she draws between mothers surveilling their children and the state surveilling mothers and children. That question of whether surveillance is wholly unjust exists throughout the book, but writers like Lisa Cartwright establish that the presence of surveillance can be what makes injustice visible, as in the case of photographs and film of detained immigrant children. The camera used “as witness and mirror to accumulate data” can make the suffering of detained families visible to the public in ways that are not possible without these surveillance technologies, showing that our entanglements with these technologies are incredibly complex.

While there is more limited space in the book dedicated to queer and trans mothers, there is a queer idea underlying how Hamacher and her collaborators think about the figure of the mother, through a specific distinction between motherhood and mothering. Alexis Pauline Gumbs describes how “motherhood is a status, a privilege granted not by the action of an individual but by the state.” Meanwhile, mothering is a community practice, and the physical and emotional actions of taking care of children. This distinction that prioritizes mothering for communities that include mothers of color and queer mothers circles back to the creation of this text in the first place as a community act of mothering. Dozens of collaborators—mothers of different classes and ethnicities and sexualities—contributed to the ideas of motherhood and mothering that shape its conception. These women all have their own experiences with surveillance, and the choice to show these relationships through interviews makes the importance of these relationships explicit.

In the collection’s afterword, Lily Gurton-Wachter reflects that although surveillance is used to control and judge mothers, the ideas put forward throughout the book advocate for “a maternal countersurveillance that seems to transform the very technologies used to control and police mothers into tools of love, curiosity and empowerment.” Hamacher and her collaborators are able to make this meaningful intervention in how surveillance can be used to help transform mothering to be more just and equitable, creating space for mothers to grow and learn from one another. The book offers scholars and creatives alike ways to engage with critical feminist studies and think through the impact of mothering in their own lives and how it can apply to their work.