Monisha Das Gupta

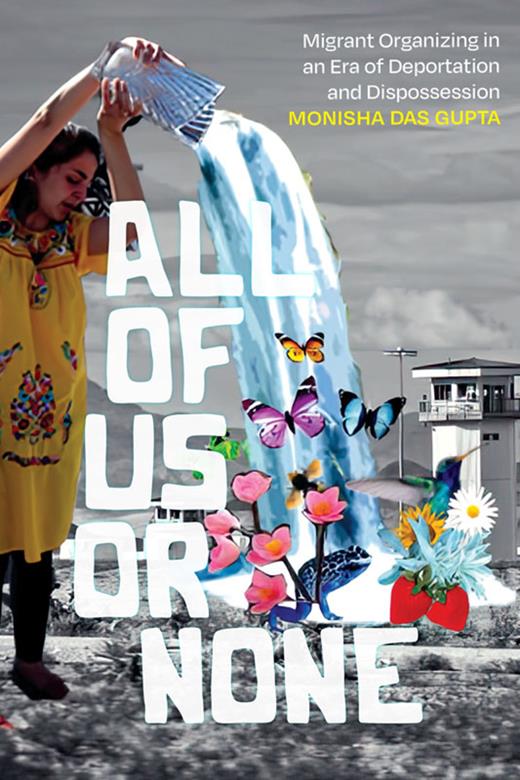

All of Us or None: Migrant Organizing in an Era of Deportation and Dispossession

Duke University Press, 2024

250 pages

$27.95 paperback, $104.95 hardcover

Reviewed by Jo Hurt

In the wake of the Laken Riley Act and the attendant surges in ICE raids and migrant precarity across the country, Monisha Das Gupta’s All of Us or None is an especially timely work on the relationship between immigration politics and carcerality—and how migrant justice activists are working to upend it. Throughout the book, Das Gupta “tells the story of contemporary antideportation organizing by and for the most indefensible of migrants and refugees—those labeled criminal aliens.” She outlines the mutually reinforcing linkages between the systems of immigration, incarceration, and settler colonialism by foregrounding the accounts of migrant justice activists and contrasts their transformative abolitionist agendas with the often nationalistic and paternalistic dimensions of immigration rights and reform movements. Throughout, Das Gupta uses a queer and feminist framework to both attend to gender and sexuality within migration justice movements and to disrupt the heteronormative and masculinist structure of US settler coloniality in and beyond immigration policy.

In her Introduction and Chapter One, Das Gupta lays out her project as a queer and feminist approach to deconstructing the relationship between immigration and carcerality as a settler colonial construct. She also outlines the history of immigration policy in the US and the place of transformative abolitionist politics within that history. Methodologically, Das Gupta utilizes interviews with and accounts from activists, her own observations as a participant-researcher, and immigration policy, which she situates within migration scholarship and a queer and feminist approach to her analysis. Central to Das Gupta’s approach to migration justice is what activists call ‘crimmigration’: “deportation tactics that depend on migrants’ encounters with local law enforcement and subjection to local, state, and federal correctional control.” Understanding immigration policy as developing alongside the criminalization of immigrant communities and the expansion of policing and incarceration allows Das Gupta to draw meaningful connections between migrant communities and Indigenous sovereignty and between settler colonialism and incarceration. At stake in her project are the “movement building possibilities” of migration justice activists, who “imagin[e] and construc[t] life-affirming alternatives that value sociality.”

In Chapters Two and Three, Das Gupta explores how two antideportation organizations, Tod@s Som@s and Families for Freedom (FFF), publicly mobilize their communities against Arizona’s Senate Bill 1070 and the public construction of the “criminal alien,” respectively. Chapter Two, “It is Our Moral Responsibility to Disobey Unjust Laws,” traces the organizing efforts of Tod@s Som@s as they engage in “unpermitted civil disobedience” in Los Angeles in 2010 and following. The ways in which Tod@s organizes against the logics of crimmigration codified by SB 1070 demonstrate how they are able to “pr[y] open a space for direct action and unpermitted civil disobedience in the migration justice movement.” In Chapter Three, “Don’t Deport Our Daddies,” Das Gupta focuses on FFF, an organization that advocates for migrants who have been charged with or convicted of a crime. These “criminal aliens” are overwhelmingly men of color, revealing “the racial and gender politics of criminality and deportation.” This chapter highlights how crimmigration threatens kinship ties within migrant communities.

Striking in these two chapters is Das Gupta’s queer feminist approach to understanding the work of these two organizations. She both attends to the gendered and sexualized dimensions of the organizers’ experiences—for instance, how the gender binary was imposed on Tod@s organizers upon their arrest or how FFF challenges gendered constructs of fatherhood and motherhood—as well as disrupts masculinist logics at work within both carceral and activist practices. By highlighting how caretaking functions as radical resistance within Tod@s’s protesting strategies or how testimonios function affectively to “build a common cause internally across difference,” Das Gupta offers queer and feminist scholars not only an analysis of gender within migration justice but also a demonstration of how feminist logics and practices can rupture masculinist ideologies.

Chapters Three and Four productively juxtapose the projects of largely youth-led migration justice movements and Indigenous peoples’ struggles for sovereignty in the face of colonial dispossession. Chapter Four, “Deportation = Genocide,” begins with an account of the Khmer Girls Alliance (KGA) and Das Gupta’s extended research within their community. KGA works to reveal “deportation as one symptom of their community’s experience of fifty years of political and structural violence” by tracing the resettlement of refugees to Los Angeles during the US’s war in Cambodia in the 1970s to the criminalization and ultimate deportation of Khmer refugees back to Cambodia following legislation in 2002. Alongside KGAs efforts, Das Gupta describes the Indigenous Tongva peoples’ movement for self-determination in order to demonstrate that “While common ground for activism may or may not emerge between the two groups, juxtaposing the two movements helps us unmask the imperial-settler carceral nature of the US state.” Finally, Chapter Five, “Not DREAMing,” describes coalitional movement-building initiated by the Immigrant Youth Coalition (IYC) of Los Angeles which brought together youth from Pacific Islander and non-Indigenous migrant communities as well as from native Hawaiian communities and “guided Hawai’i’s youth activists toward contextualizing Oceanic decolonial projects in the critiques of crimmigration.” In particular, IYC’s queer framework resists “assimilative DREAM narratives ensconced in neoliberal respectability politics.” These two chapters reinforce Das Gupta’s commitment to transnational feminist analysis (already established in her first book, Unruly Immigrants) by highlighting the extension of immigration logics through US imperialist projects in Cambodia and Micronesia and, likewise, the instantiation of settler colonial logics in stateside projects of immigration and Indigenous dispossession.

All of Us Or None offers several openings for continued intersectional scholarship on immigration and migration justice organizing. Her discussion in Chapter Two, for instance, of the relationship between organizers and time calls to mind the ways that disability scholars discuss ‘crip time,’ which could prompt questions of how ableist logics undergird and reinforce immigration policy and carcerality. Das Gupta’s accounts of US immigration history’s impacts on and intersections with Indigenous politics also leave room for further scholarship. Although Chapter Five, in particular, is able to draw clear connections between migration justice and Indigenous sovereignty movements, there are opportunities to expand on, for instance, how SB 1070 was not only anti-immigrant, but also enacted settler colonial claims to the territory of the United States that are anti-Indigenous (Chapter Two) or how FFF’s work defending criminal aliens has “enormous potential to link migrant justice to Indigenous projects of decolonization” (Chapter Three). Das Gupta has, as she says in her Conclusion, developed a substantial and convincing foundation for how “deportation is a carceral technology through which the United States stabilizes its settler imperial power in the face of Indigenous sovereignty,” and her work invites both academics and organizers to continue to interrogate the intersectional powers of control at work within US immigration policy.