Keiko Lane

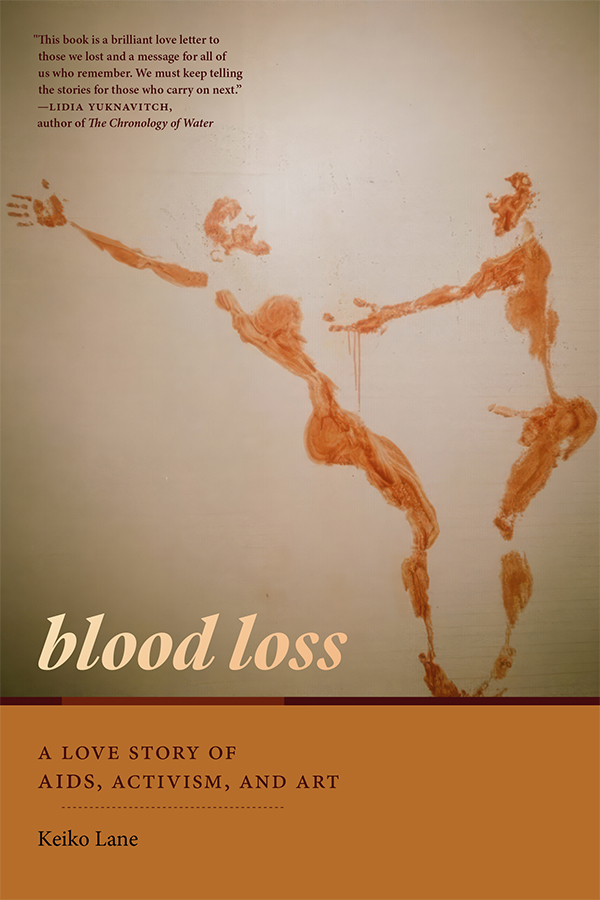

Blood Loss: A Love Story of AIDS, Activism, and Art

Duke University Press, 2024

300 pages

$26.95

Reviewed by Mary Fons

In 1992, the Los Angeles Times reported that one out of every 200 people living in Los Angeles County was infected with HIV, and one out of every 2,000 had contracted AIDS. The area’s numbers were the highest of any county in California and exceeded the national average. The mortality rate of individuals infected with AIDS was seventy-two percent.

In Blood Loss: A Love Story of AIDS, Activism, and Art, author Keiko Lane offers a personal account of living and loving through the “constant, breathless loss” of the AIDS crisis in LA in the early 1990s. As the disease tears through her kinship network, claiming the lives of young gay men, Lane must begin the lifelong process of working through profound grief and rage while aching to remember everything she can before the past claims the memories of her friends as quickly as the disease claimed their lives.

Lane, an independent scholar and practicing psychotherapist, begins her affective history when she was just sixteen. A queer high schooler with a heart for activism, she becomes involved with AIDS activist organizations ACT/UP and Queer Nation. In these groups, Lane finds her purpose and her people. We follow her over the course of the next few years of emotional and political upheaval as she meets friends and lovers at rallies, nightclubs, and, eventually, in hospital rooms. Lane takes an auto-theoretical approach in the sharing of her lived experience; pieces from her archives, including the contents of several letters never mailed (“unsent fragments”) and the addition of ‘marginalia’ in the form of short lists of statistics from year to year, show Lane experimenting with form; lyric language lends a meditative tone to the prose. Particularly evocative is the choice to print a number of pages in solid black with the names of the friends who passed away written like headstones at a gravesite.

Certainly, Lane is a reliable narrator in her accounting of those years; there’s no doubt that what she says happened, did. But the author’s persona—the narrative voice a memoirist must use to make meaning from the past—feels underdeveloped. Memories painful and sweet swirl across the pages without enough insight from Lane, now in her fifties. Personal narratives attempt to analyze why things happened; not just how or when. In Blood Loss, deeper insights are sidestepped, replaced by lengthy strings of hypothetical questions: “What is symbol? What is real? What is representation? What is meaning-making in a plague that has challenged us to make meaning without a context from which to cull pattern or template?” Existential questions like these may not have concrete answers; Lane acknowledges this. But without more focused attempts from Lane to make meaning out of it all in the decades since, Blood Loss feels more like a diary than a memoir with something to impart to the reader.

Like the rest of the country, most infected with HIV/AIDS in LA County were in their twenties and thirties, but the community of activists crossed every demographic. Lane’s choice to begin her story during her teen years makes Blood Loss a useful contribution to firsthand accounts of the AIDS crisis. Yet the fact Lane was barely old enough to drive (and not yet able to vote for the legislation that could help her loved ones) deserves more attention in the story. When she becomes secretly sexually involved with Cory, a gay, Irish-Puerto Rican artist who is HIV positive and nearly ten years her senior, Lane is a minor. “I’m an underage dyke sleeping with an HIV-positive fag,” she says at one point, but neither the age disparity nor her lover’s possible motivations are satisfactorily assessed all these years later. Later, Cory asks his sixteen-year-old secret girlfriend to help him commit suicide if the disease gets “bad.” When the time comes, Lane refuses. Cory is furious, shouting, “You promised” and “Why won’t you help me?” Lane takes the blame for his behavior: “It was a test,” she writes, “and I failed.” Just one year later, Lane begins another clandestine relationship with a gay, HIV positive man. Steven, a promising novelist, who like Cory later died of AIDS, was thirty-eight at the time of his affair with Lane, then seventeen. It is not surprising that the anguished young woman finds herself at one point unable to cope with the trauma and heartbreak around her; before leaving for college, she stands in the kitchen and tries to cut herself. The scene ends with Lane choosing not to inflict self harm, but without more reflection from Lane on the situation as she has processed it over the years, we come away from an incredibly intimate situation portrayed without much connection to Lane then or now.

In the fall of 1985, more than four years after the first cases of HIV had been reported, President Reagan publicly said the word “AIDS.” It took three more years before he allocated funding for AIDS research, which eventually resulted in trials of the first antiretroviral drugs for HIV/AIDS patients. Agonizingly slow as it was, progress in the fight against the HIV/AIDS epidemic was the direct result of activism on the part of groups like those Lane was involved with, as well as medical professionals and members of affected communities across the nation. We owe the survivors a debt of gratitude for preserving through what many have described as a war, with all the trauma and fallout wars inflict.

In the book’s opening scene, Lane is tending to Cory, who has been badly wounded at a protest against governor Pete Wilson’s veto of AB-101, a law that would’ve protected HIV/AIDS-infected individuals from housing and employment discrimination. Today, as the Trump administration rolls back legal protections for queer and trans Americans, insights from those who navigated similar struggles are needed more than ever. Readers may identify with the emotional elements of Lane’s experiences and find consolation in knowing the previous generation felt similar feelings of love, helplessness, and fear. But when Lane asks strings of big questions—“What does it mean to want something that one can’t have in the present tense? Or in the future tense? Does the impossibility of a future make the present already vanish from reach?”—without leading us through her own thoughts after years of reflection, the burden shifts to the reader to find their own answers.