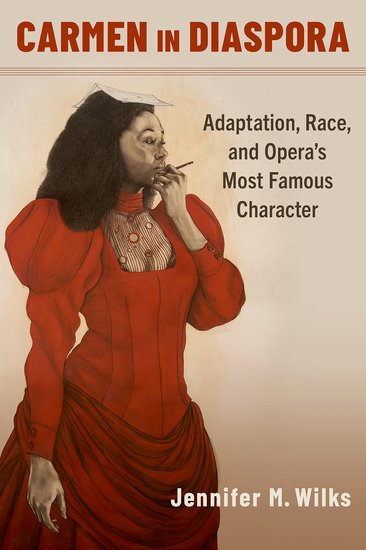

Jennifer M. Wilks

Carmen in Diaspora: Adaptation, Race, and Opera’s Most Famous Character

Oxford University Press, 2024

262 pages

$80.00

Reviewed by I. B. Hopkins

“Carmen has generated its own diaspora,” Jennifer M. Wilks argues in her rich and wide-ranging new monograph on the opera repertoire’s sexiest, most perennially popular character. While the figure of the elusive Romani cigarette factory worker first became a sensation in nineteenth-century Europe, her singular magnetism and Georges Bizet’s score have continuously been remade through adaptations over the past century and a half. Cataloguing the panoply of so many Carmens, “if done thoroughly, would result in a multivolume work,” Wilks notes; accordingly, her focus in this cultural history is more narrow and more pointed in effect. Eight adaptations of Carmen in the African diaspora serve as the primary case studies through which she elaborates the ways in which the recurrent figure of Carmen herself persistently troubles intermingled conceptions of race, ethnicity, and gender across multi-continental settings. Situating this exploration in the discourse of adaptation studies, Wilks makes clear that although the world-famous opera remains a product of white male writers close to the heart of European imperial power—relying as it does on exoticizing motifs—successive artists continue to find tremendous potential for subversion and critique through the opera precisely because it stages direct challenges to social norms. “To transpose Carmen to African diasporic contexts,” she reasons, “may not be an uprooting of the story so much as it is an opportunity to acknowledge the tangled cultural roots beneath it.” This project derives inspiration from critical readings of iconic figures advanced by scholars such as Deborah Paredez (Selena), Domino Perez (La Llorona), and Elizabeth Young (Frankenstein). Like each of these, Wilks’s understanding of the character operates as a cipher through which to comprehend the cultural matrix able to produce this Carmen at this time and place.

Carmen in Diaspora admirably substantiates the need for attention to the tradition of Black Carmens, a phenomenon the book covers over a period of more than a century across multiple genres. Tracing comparisons between Roma and African diasporic representations, Wilks deliberately thwarts conflation between ethnic categories while also offering productive context to various manifestations of the analogy. To wit, Chapter One destabilizes any notion of Carmen as a ‘master text’ by illustrating the social worlds of Prosper Mérimée (author of the 1845 novella on which the 1875 opera is based) and Bizet, two men whose travels and diverse relationships point to real investments in the negotiation of difference and friendships with women who challenged the conventions of nineteenth-century gender codes. Turning then to novels of the Harlem Renaissance, Chapter Two surfaces the underlying thematic energies that animate interest in the story as well as its adaptability. Namely, Carmen evokes irresistibility across the social divisions we inhabit, which permits every instance to both call forth preconceptions about otherness and to exceed them. Through a series of Carmen citations in Wallace Thurmond’s The Blacker the Berry (1929) and Claude McKay’s Banjo (1929) and Romance in Marseille (2020), Wilks reads an extension of the intellectual and artistic vision of the turn-of-the-century African American ‘Black Bohemian’ counterculture. In the cultural imagination, the Bohemians (which is to say Romani) represented for many thinkers and performers a kind of unfettered mobility that resisted bourgeois notions of respectability conceptualized as the ‘New Negro’ movement. Thurmond’s and McKay’s modernist fictions might be said to imagine Black Bohemia through select characters’ abilities to transcend gender, nationality, race, and class, even if they remain unwilling to grant self-determination to the women of color around which their narratives turn.

Chapters Three and Four pivot to filmic interpretations of Carmen, though with notably different analytic strategies. Two African American versions anchor the first of these in a discourse about the star-making potential of the role for two multi-talented Black performers seeking to transition into mainstream celebrity after success in their musical careers. For these purposes, Dorothy Dandrige’s Oscar-nominated performance as the lead in Carmen Jones (1954, directed by Otto Preminger, an adaptation of the stage musical by Oscar Hammerstein II) stands in comparison to Beyoncé Knowles-Carter’s acting debut in the MTV-produced television movie Carmen: A Hip Hopera (2001, directed by Robert Townsend). While Dandrige’s Carmen achieved widespread critical acclaim, Wilks contends that her association with the role ultimately pigeonholed her in the mid-century Hollywood casting economy as sensuous and ethnically-ambiguous, essentially the “exotic woman as a supporting character.” Knowles-Carter’s Carmen, by contrast, exemplifies the United States’s transition “from the rise of multiculturalism in the 1980s to the advent of postracialism in the early 2000s.” Knowles-Carter’s career has continued to flourish, of course, and Wilks draws a direct line from the numerous (and ongoing) versions of Beyoncé to the mutable and rapacious character in Mérimée’s original text. (One can almost imagine Cowboy Carter’s rendition of the Toreador song.) Yet, it is the respectively Senegalese and South African films considered in Chapter Four which Wilks claims “emerge as two of the most compelling Carmen adaptations”—Karmen Geï (2001, directed by Joseph Gaï Ramaka) and U-Carmen eKhayelitsha (2005, directed by Mark Dornford-May). Both embrace their setting in modern-day Africa to transpose the opera’s depictions of gender, ethnicity, and labor in a new setting with new musical idioms. The former uses vignettes to deconstruct the narrative while the latter adopts a naturalistic approach. The shift that Carmen in Diaspora tracks most intently, though, concerns the title characters’ relationships to the other women in the communities, their social networks. Although both are “charismatic individuals who command the attention of those around them [they do so] while also drawing sustenance from community.” Operating at both the levels of gender-based discrimination as well as postcolonial politics, these heroines prove innovative by dint of their turns away from choosing between male partners as in the source text and toward questions of freedom and solidarity among women.

The final case study returns, in Chapter Five, to the stage and realizes a broadly diasporic vision of the text. Since it was conceived by British director Christopher Renshaw and written by Renshaw, Cuban playwright Norge Espinosa Mendoza, and British dramatist Stephen Clark, Carmen la Cubana (2016) has undergone numerous iterations across several countries, in three languages, and with the artistic input of a truly international creative team. Set in Cuba during the late days of the Batista regime, Carmen la Cubana explicitly draws on Mérimée’s, Bizet’s, and Hammerstein’s versions of the story while placing a mulata Carmen at the center of the political unrest that would become revolution. Wilks carefully dissects the adaptive choices as well as critical response to the musical play and lingers with the unresolved tensions it produces between the Afro-Cuban woman as a symbol of nationalism and the violent end she meets. “[A]n act of Black feminist revision, of seeing anew, would mean that Carmen’s death would no longer be the narrative and political prerequisite for the triumph of the 1959 revolution” and the full expression of liberation for which it stands.

Carmen in Diaspora concludes, then, with a brief Epilogue that outlines significant recent productions of the opera directed by women and engaging in the broader African diasporic crosscurrents explained in the book. Showing how adaptation, context, and (re)productions all talk back to one another, Wilks’s monograph expertly demonstrates an analysis of diffuse cultural objects read through the figure of a singular icon.