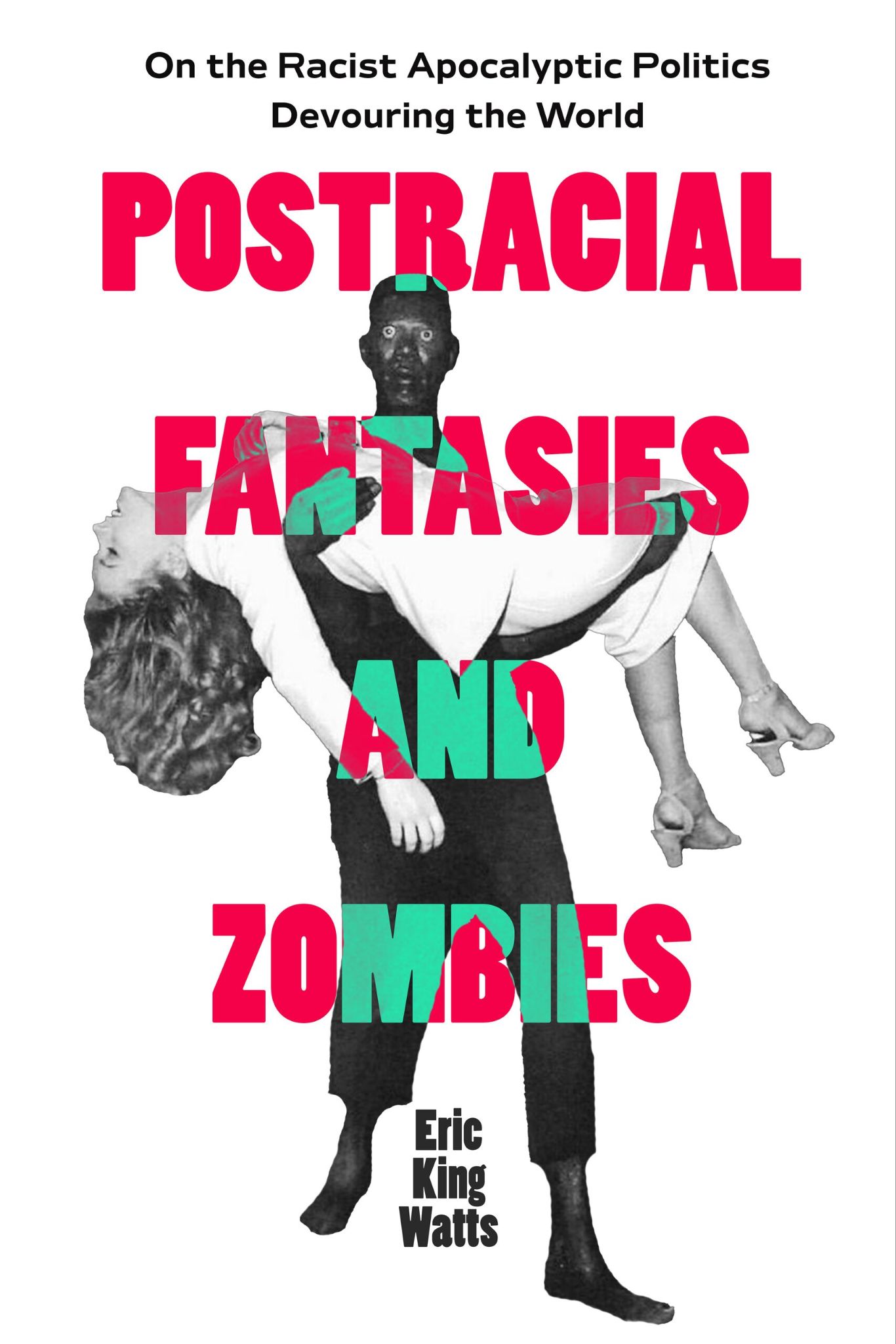

Eric King Watts

Postracial Fantasies and Zombies: On the Racist Apocalyptic Politics Devouring the World

University of California Press, 2024

230 pages

$29.95

Reviewed by Isabella Neubauer

Eric King Watts’s Postracial Fantasies and Zombies: On the Racist Apocalyptic Politics Devouring the World examines key moments in the history of the zombie through the lens of biopower. The key contention underlying Watts’s book is that major zombie media appears during moments of anxiety around race, which Watts describes as instances of the postracial. Watts writes that “The postracial promises that there is a place beyond race, but such a promise is a threat to white supremacy and triggers anxieties of white identity formation in general.” While far from the only instances of the postracial worldwide, Watts focuses specifically on postraciality in four instances. In his first chapter, Watts discusses the Haitian Revolution; in the second, the United States’ military occupation of Haiti in the early twentieth century; in the third, the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s; and in the fourth, Barack Obama’s presidency. During these times, Watts argues influential zombie media (such as 1968’s Night of the Living Dead) was produced in direct response to a perceived threat to white identity via the possibility of greater equality for Black people.

Postracial Fantasies and Zombies is not, despite its classification on the copyright page, a book about zombies in motion pictures. Nor is it solely a book about fictional zombies—Watts is dedicated to the social phenomenon of the zombie. While fictional zombies certainly appear in its pages—with Chapter Two containing an analysis of White Zombie (1931) and much of Chapter Three dedicated to Night of the Living Dead (1968)—Watts’s true focus is on the social process of zombification, through which media and white culture turn Black people into zombies. Only the final sections of each chapter are devoted to media analysis, with the bulk of each chapter creating a solid theoretical platform for analysis of sociocultural phenomena (and, eventually, media).

Chapter One, “Name something you know about zombies,” focuses on the origin of the zombie legend on Haitian plantations, and the ways in which the Haitian revolution of the early nineteenth century and its promise of a free Black state sparked white imperial anxieties. This chapter also introduces what will be a core concept throughout the book: zombies as a biotrope. Derived from Stuart Hall’s revision of Foucault, the biotrope is an assertion of “an ontogeny of difference (bio) into sociality (trope) [ . . . ] Such discourse takes the blackness of skin and projects it inward toward biological matter and processes.” Watts retreads what may be familiar ground for some readers in order to build a solid foundation for the central thesis of his book: that while many late-twentieth and twenty-first century zombie narratives disavow the creature’s connection with its origins among Haitian slaves, the zombie continues to be a figure for the slave. He specifies that, following the withdrawal of French colonial power from Haiti and later the United States’ abolition of slavery, “The biotrope of the zombie was seized upon as if it could replace the slave.” Following the withdrawal of colonial troops from the island in 1804, the transatlantic print culture of the day wrote about Haiti as a nation of brutes, capable only of violence. While the tale of the zombie was not yet commonplace, the press was already working to zombify the Black population of Haiti by denying them humanity.

In Chapter Two, Watts moves forward in time to the early twentieth century, immediately following the United States military occupation of Haiti. Continuing his analysis of print culture, Watts explores how William Seabrook’s The Magic Island (1929), a work of “fantastical nonfiction,” presented the island—and its zombies—to the world. The United States military began its occupation of Haiti in 1915, but American companies had been employing Haitians in the sugar fields long before that. Seabrook’s travels through Haiti took place in the 1920s after around a decade of continuous occupation. Watts builds upon Foucault’s ideas of biopower in this chapter to further his concept of the biotrope. In this chapter, Watts analyzes the 1931 film White Zombie, a film wherein the white heroine is (temporarily) zombified. One need not have black skin to be blackened through the deployment of the zombie biotrope, Watts contends: “The breakdown (or breakthrough) that brings on the postracial unleashes logics and practices of blackening, wherein anyone whomsoever may be violently seized and made to pay penance.” The perceived linkage between biology and sociality inherent in the biotrope allows for a person to become socially blackened through the biological process of zombification.

In Chapter Three, Watts leaves Haiti for the United States, focusing on the racial turmoil of the Civil Rights movement and the late 1960s. This chapter relies heavily on the concept of perversion—specifically the perverse nature of the film Night of the Living Dead (1968) and its audience. Ben, the film’s main character, is Black—a fact which fascinated audiences, but on which filmmaker Romero refused to focus. Watts writes, “This structure is perverse due to its disavowal of and investment in the astonishment that first-time audiences no doubt experienced as they gazed upon what Franz Fanon remarked as the unexpected epidermalization of blackness: ‘Look! A Negro!’” Ben’s race, however, is not the only aspect of the film which reflects the racial anxieties of the 1960s. The zombies—who, as Watts has established throughout the previous chapters, represent a contagious form of blackness—kill the film’s white characters, while law enforcement kills Ben. Ben could not survive because, in Watts’s theorization of the zombie biotrope, to be Black is to already be a zombie.

Chapter Four continues this thread via analysis of people preparing to fight real-life zombies, as featured in the documentary film Zombie Preppers (2012). While “Biotropes of infection and contamination have long been the weaponized speech of political regimes busying themselves with border patrols and home defense,” prepping for a zombie apocalypse, Watts argues, is often a method of reasserting white male identity over the perceived threat of a diversifying world. It is no coincidence that the documentary was released in 2012, the year the first Black president of the United States won re-election. “Enjoyment of the postracial is pegged to anxieties of a post-white society and the exertion of white (masculine) sovereignty as a mode of racial reclamation—as a violent, murderous way to set things right (again).” Watts’s use of “(again)” recalls the slogan of Donald Trump’s 2024 campaign for the presidency, “Make America Great Again.” While Postracial Fantasies and Zombies was published before Trump’s re-election, the political and social forces leading up to it were already brewing—as revealed by the Zombie Industries target practice dummy which looked suspiciously like Obama.

Perhaps the strongest aspect of Postracial Fantasies and Zombies is Watts’s writing style. While the heavy reliance on Foucault, Hall, and other theorists could easily alienate unfamiliar readers, Watts presents his argument in a form digestible by zombie enthusiasts and academics alike. In a world fascinated by zombies, theorizing the relationship between zombies and their sociocultural contexts reveals the racial politics inherent in the longstanding pop cultural phenomenon.