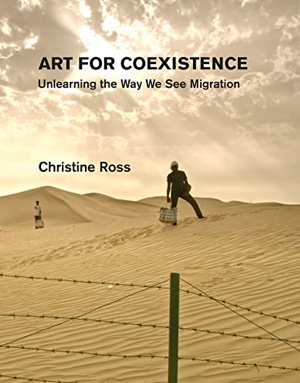

Christine Ross

Art for Coexistence: Unlearning the Way We See Migration

MIT Press, 2022

406 pages

$38.00

Reviewed by Shania Montufar

Contemporary art is not absent of dialogue surrounding displacement, migration, and diaspora. Despite this, in Art for Coexistence: Unlearning the Way we See Migration, Christine Ross asks the art world to reconsider the frame it employs to display migration. The text engages with the central question: what do European and North American art contribute to the understanding of migration, and why is this contribution critical to the development of the twenty-first century? In posing the question, Ross calls for the visibility of art of “coexistence,” which showcases the intrinsic and troubled connections between migrants and citizens of the states they enter. Through installation, performances, photographs, sculptures, graffiti, and beyond, Ross indicates how artists combat the idea of a “we” vs. “them” migration crisis and instead demonstrate the negotiations and violence of coexistence. Art for Coexistence consists of four primary arguments: 1) contemporary artist respond “disobediently” to standard conceptions of the migrant “crisis” 2) art has the political potential to arrange “sensibilities” 3) rearrangement can only happen through an iterative and awareness-driven artistic process 4) imperialist museology has failed to display diverse perspectives surrounding migration. Using these central arguments, Ross tells us that in order to combat imperialist museologies and gazes in the art worlds’ conception of migration, critical artistic perspectives must be historical, responsible, empathetic, and employ storytelling. It is only through this thorny and ponderous conception of migration art that a luminous conception of “coexistence” comes to be. In this way, Ross calls for the revealing, contesting, rethinking, delinking, and relinking of interdependencies in how art showcases migration processes.

How does the injury, destruction, and dehumanization of migrant groups become politically accepted? This question is posed as the text opens. Using the installation “Undocumented Migration Project” (2019) as a frame of reference, Ross explains that necropolitics, a biopolitical way of normalizing the human suffering of one’s “enemies,” has dominated Western conceptions of migration. Thus, as Ross explains, this conception conveniently erases a history of European colonialism and American interventionism to explain displacing forces. Namely, Western Union: small boats (2007) is a three-screen film chronicling refugees leaving Africa by boat, juxtaposed with a history of both the Middle Passage and contemporary luxury European tourism. Ross refers to this example to showcase how contemporary artists “disobediently,” critically, respond to notions of migrant crisis rooted in necropolitics and ahistoricism. Lastly, in this first section, Ross overviews the use of montage and “aesthetic stress” in critical and contemporary migration art.

The second section of the text addresses the question of responsibility. Whose responsibility does contemporary art call for? Are aesthetics and responsibility compatible? This section largely showcases how contemporary artists grapple with asking viewers for responsibility in addressing suffering. Here, Ross describes La Promesa (2012), a 15-ton rectangular block salvaged from Ciudad Juárez by Mexican artist Teresa Margolles. La Promesa also consists of a performance in which volunteers scrape the block with their hands, leaving fragments behind, indicating the relationship between violence, displacement, and migration. Ross refers to this work as a successful reflection on a “collective deployment of care” in which a coexistent artistic lens comes to fruition. In this instance, responsibility becomes a community endeavor taken up by those viewing and acting in the performance. Expanding on this idea of a viewers’ engagement in an artistic process related to migration, Ross contemplates the role of empathy. She poses: why and how does empathy matter in artistic practices addressing modern-day migration? Why do artistic practices persist with calls for empathy despite findings that the prosociality of empathy should be mistrusted (or facilitated differently)? This section of the text ends with a contemplation of the role of storytelling in successful migrant art. The concept of empathy is especially compelling in that Ross asks how primarily white, upper-class artistic audiences might understand and empathize with migrant art. Should empathy from those audiences be elicited? Can it be elicited? Should a more holistic approach, such as that of idealistic coexistence be adopted?

At large, the text represents a hearty dialogue about the politics enshrined in contemporary art, as well as the history of imperialism and colonialism built into the spaces. Ross shows us how brave, critical artists combat the notion of a “migrant crisis” to showcase the multiplicity of realities, both dark and luminous, of migration processes. She further complicates how migrant art is shared by explaining the challenges of empathy and storytelling, especially when the art is shared with a primarily white, upper-class audience.

I find Ross’s aspiration for an “art for coexistence” compelling in that it considers diverse and marginalized perspectives in the artmaking process. Further, her call asks us to expand, rethink, and digest our preconceptions about migration and artmaking. Her showcase of Undocumented Migration Project (2019), Western Union: small boats (2007), and La Promesa (2012) provide keen examples of the conflicts artists face when addressing their audiences and theoretical perspectives. Namely, her contemplations related to empathy and necropolitics are especially valuable in that they juxtapose the segmented realities created through both inequality and art-spaces.

At times, the conception of coexistence does not, though, go far enough to advocate for justice for migrant experiences in the art-world. Contemporary art does not just frame migration as a “crisis,” it also excludes and marginalizes voices that seek to diversify understandings of migration. In this sense, Ross leaves space for a dialogue about actionable improvements and access in contemporary art spaces. Thus, if Western contemporary art depends on necropolitics, and a “them” vs “we” mentality, how do migrant artists combat those processes (through both their artistic and political processes)? Ross provides an overview of the critical works created by these artists but does not tell us how they negotiate their own experiences in the contemporary art world. In this sense, she provides a keen overview of the central conflicts existing between traditional and contemporary framings of migrant experiences but leaves space for us to consider the implications