Joyce N. Bennett

Good Maya Women: Migration and Revitalization of Clothing and Language in Highland Guatemala

University of Texas Press, 2022

176 pages

$24.95

Reviewed by Amanda Tovar

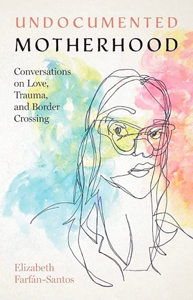

In Elizabeth Farfán-Santos’s seminal text Undocumented Motherhood; Conversations on Love, Trauma, and Border Crossing, Farfán-Santos challenges the hegemonic nature of preordained heteronormative and patriarchal expectations of motherhood. Farfán-Santos discloses what may drive parents—mothers specifically—to decide to cross international borders without state authorization, emphasizing the various states of anxiety that influence making such a decision. In illuminating all that goes into border crossing for mothers, Farfán-Santos demands the reader shed any and all preconceived notions of what is typically portrayed by the media and repeated by xenophobic antagonists who are against migration as unmotherly actions—crossing international borders without their children or leaving children with coyotes to cross international borders separately.

Farfán-Santos’s academic background is in anthropology, and Undocumented Motherhood provides a radical and provocative contribution to the field via her methodological approach of testimonios (testimonials). Anthropology, as a study, often involves the study of people, but Farfán-Santos places herself within her research. She utilizes interviews with her personal friend and main interviewee, who she calls Claudia García, about her experience as an undocumented woman parenting her disabled and undocumented daughter, Nati. Farfán-Santos also weaves in her own familial experience by providing interviews with her mother, grandmother, and sometimes narrating her own experience and memories.

Undocumented Motherhood also includes blind contour drawings, which the author considers studies. Blind contour drawings are created when the artist intentionally does not look away from the subject while drawing them out. Farfán-Santos argues that the images are equally as imperfect and complex as the artist’s subject. She argues that since the images are imperfect, they will never be able to encapsulate the subject’s full personhood thus making them an effective representation of human complexity as they mimic the fluidity of life. Additionally, the narration in Undocumented Motherhood constantly shifts from Claudia’s voice to Farfán-Santos’s mother and grandmothers voice, and sometimes to Farfán-Santos’s own voice. This anthropological approach of utilizing artwork, testimonios, shifting voices, as well as autoethnography for this all-too-common US. experience is extremely poignant and vital for the field.

Chapter One details Claudia’s traumatic experiences while crossing the border—a decision she and her husband made when they discovered that their daughter, Nati, was “sick in her ears.” This decision ultimately led to Claudia experiences of trauma ranging from being held in ICE detention, forced to leave Nati with a coyote so she could cross first, and unwillingly listened to a woman be raped. Chapter Two describes an entirely different border that the García family had to navigate—the medical industrial complex that informed their decision to flee their home. Farfán-Santos juxtaposes the García families experience with the lack of quality health care access to what Farfán-Santos’s own mother recalled as “unmemorable” for her family because to them citizenship equated to access. Ultimately, the most important question Farfán-Santos raises is, why would any doctor who took the Hippocratic Oath deny a child life-changing surgery? Furthermore, in Chapter Three, Claudia reveals that she has fibromyalgia, a chronic pain condition that many doctors often associate with trauma. As a medical anthropologist, Farfán-Santos considers Claudia’s experience with immigration, leaving Nati with a coyote, Nati’s medical negligence and exploitation, and cervical cancer and a partial hysterectomy, and makes the critical tie to her fibromyalgia diagnosis. These stories brought the author to reflect on her own experience post the birth of her two children. She experienced hemorrhaging after each birth and contends both were directly tied to her family’s medical history. Chapter Four documents the important role comadres and chisme play for Latinx women like Claudia, Farfán-Santos’s grandmother, and other family members. Farfán-Santos frames comadres and chisme as lifelines and pillars as a direct challenge to patriarchal narratives and ultimately as radical acts of love. In Chapter Five Farfán-Santos focuses on Nati’s experiences as an undocumented child in the United States. Claudia detailed Nati’s experience of gross negligence and bullying while attending school, the very same American education system that influenced the García’s to come to the US. Ultimately, at the root of it all, Nati was struggling and perhaps frustrated because she was having difficulties communicating and was being mistreated by her peers and grown adults all while having an insatiable desire to hear. Not only did Nati have to face the world as someone who was unable to hear and be heard, but she is also a girl and a Mexican girl at that. Racism, xenophobia, and ableism dominated nearly every aspect of Nati’s life and still Farfán-Santos describes her as someone with a “fighting spirit” who is also special, and because of that she has much hope for Nati’s future. And finally, the concluding chapter Claudia states that immigrants making their way to the US are coming to work, and despite that the media was reporting on government attempts to slow that down via child separation laws. She continues to stay that even with all that is happening concerning immigration she would do it all over again because despite all of the trauma and troubles they have experienced together, Nati has made progress and if they had stayed in Mexico she would just be “playing in the dirt.”

While Claudia’s acts may be portrayed by some as unmotherly or otherwise negligent, Farfán-Santos expresses how this action, too, is a selfless maternal act of love because Claudia was faced with the difficult decision of staying in the destabilized region of Mexico or at least attempt a life in the United States because she genuinely believed that the journey of undocumented motherhood was Nati’s best possible chance at acquiring access to quality health care. Ultimately, Farfán-Santos argues, the sacrifice Claudia made to migrate to the US cannot be reduced to criminality due to her unlawful residency. Likewise, the decision Farfán-Santos’s mother made to leave her two children behind in Mexico for some time was done to ensure financial stability.

Ultimately Farfán-Santos’s work serves as a challenge to the anthropological discipline as it is more methodologically whole than most human investigations. Her work aims to tackle the ways in which the geopolitical border between the US and Mexico hinders motherhood and children for generations. Her work demands a forceful reexamination of undocumented motherhood—an often overlooked, hyper-criticized and judged, and ultimately politicized experience that she states is the experience of millions of women in the US and is largely missing from the literature on parenting. She demands we examine the true nature the selfless actions required for mothering while undocumented. Claudia did not want to leave her hometown in rural Mexico for the United States, nor did she want to leave her daughter, Nati, with coyotes in El Valle so she could cross the geopolitical border first. On November 4, 2021, Nati received her cochlear implantation surgery, a direct result of her mother’s sacrifice and selflessness act of placing her children first and leaving her homeland for the US.