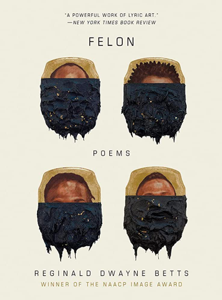

Reginald Dwayne Betts

Felon: Poems

W. W Norton, 2020

96 Pages

$15.95

Reviewed by Amarainie Marquez

In his formidable third poetry collection, Felon: Poems, Reginald Dwayne Betts illuminates the dark spaces of the US prison system and sheds light on what prison takes from people when they become incarcerated, with an emphasis on the lingering consequences even after release.

The collection opens with a ghazal – a form of poetry known to express both the pain and beauty of love. The speaker navigates readers through the vast attempts at grappling with the social and mental struggles following release. Betts’ couplets are punctuated with “after prison,” illustrating the way prison leaves a stubborn mark that finalizes thoughts and people, like a wound may leave behind a scar: something that not only one may fail to erase but is always reclaiming itself in the form of obstinate reminders. The speaker notes, “Them fools say you can become anything when it’s over. /Told them straight up, ain’t nothing to resurrect after prison.” The beauty of being released and the pain of knowing one is never truly free after incarceration, because the experience becomes you, “…it’s prison’s vastness your eyes reflect after prison” and this lingers at the edges of each page. Betts grapples with the harsh realization that is not limited to years and time lost but is reflected in the way the shadows of time spent in prison sticks to each step one takes. Its darkness follows, haunts….

In “The Lord Might Have Given Him Wings,” Betts calls forth the imagery of Lazarus: of resurrection after death, notes “No one calls him/kid” because when one is Black, they are a man capable of giving forth penance in the form of life at any age, recalls “The holy/have left, we know” as Faith quakes in the wake of the dark, sealed with imagery of corridors “long/as the Atlantic” and each cell “a wave threatening/to coffle him” as a final evocation: the prison system as an upright mirror at the face of slavery.Betts thumbs through the various wounds of incarceration and his personal experience of the prison system firsthand by the use of poems that range in form and demeanor. Some feel like a conversation, retelling a moment with all the honesty and frankness of a friend. Others trace a lyrical image abstractedly and urge the reader to sift through the darkness and listen carefully. Betts crafts these wounds and gives them names, retelling how the past bounces off walls and echoes; relationships in flux deteriorate when mixed with whiskey and a locked door; the knots and nuance that accompany an experience when the speaker becomes a public defender; bending political commentary into the blooming and illuminating of a poetic hand and reworking legal documents with redaction, with darkness (as is a blackout poem’s custom, and as the

speaker confirms, “redaction is a dialect after prison”) to reveal the true obscurity in the legal system.

Betts tackles fatherhood, manhood, one’s place in their familial unit, in their community, in the world. He spotlights poverty and the people in its grip, a topic often shunned to dark places, making space for it to speak. His poems wrestle with alcoholism, religion, death, violence in all its nuanced forms, longing, mistakes, and the accompanying regret. Youth and age, the messiness in between as what dictates “old enough” is often blurred in the face of lived choices, the justice system, and community.

The collection ends with “House of Unending” – a numbered lucky number seven sonnets that run behind one another in a seemingly epic fashion. The speaker asserts, “There is no name for this thing that you’ve become:/” but attempts to collect those that are likely to fill the space, “Convict, prisoner, inmate, lifer, yardbird, all fail.” Memories are splayed across the pages, emotions harnessed and released, there is a raw truth that settles itself in the ink and induces an awe that the reader can only motion toward an understanding of. “Jesus died for somebody’s sins but not mine.” The speaker seems to still be tackling the darkness speaking to his past self and reflecting on what he knows now. This powerful and deeply moving collection of poems speaks to something intimate in Betts’ experience while recalling universal truths we can all nod to. The darkness of our prison-industrial complex is illuminated in this work, the lives it takes, how it molds and shifts beings who are after all, people before anything else. This masterfully crafted collection of pieces garners its light through its searing honesty of life before, during and after incarceration as an impactful and compelling art that demands to not be overlooked.