Jennifer Lynn Kelly

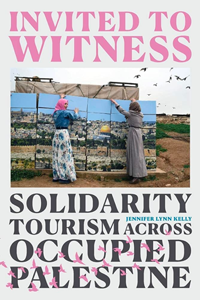

Invited to Witness: Solidarity Tourism Across Occupied Palestine

Duke University Press, 2023

337 pages

$28.95

Reviewed by Neville Hoad

Invited to Witness: Solidarity Tourism Across Occupied Palestine offers a meticulously researched, scrupulously contextualized and methodologically innovative account of now nearly forty years of what has come to be called “solidarity tourism” in historic Palestine, from the first intifada to the present. Building upon Edward Said’s formulation—“the permission to narrate”—Kelly, an associate professor of Feminist Studies and Critical Race and Ethnic Studies at University of California, Santa Cruz, concatenates an extraordinary interdisciplinary archive, ranging from ethnographic interviews with tour guides and delegates/tourists, critical analyses of television cooking shows, international agreements and human rights reports, theories of settler-colonialism, inter alia. This archive both narrates and analyzes the ways in which tourism and solidarity and their intersections facilitate and confound the ability of Palestinians to tell their own stories and contest the stories that have been told about them by political forces invested in their erasure.

Taking its lead from some specific Palestinian cultural and more specifically topographical practices, the book is careful to look both forward and backwards. Kelly asks “what kinds of anticolonial imaginings are made both available and impossible through solidarity tourism?” Resolutely aware of her own implication in the practices she critiques, Kelly works hard not to “replicate the colonial calculus of veracity that positions only tourists and delegates as truth-telling subjects, only tourists and delegates as witnesses to colonial violence in Palestine.” And then more directly: “I thus tell this story as a settler in two places, a non-Indigenous faculty member working on Amah Mutsun Tribal Land at my institutional home of University of California, Santa

Cruz, and a non-Palestinian researcher in Palestine who was able to move freely on land that is not my own. My research, in this way, documents, archives, and indicts the shared settler-colonial practices that have enabled it.” The simple and effective praxis for confounding this colonial calculus of veracity is to cite Palestinians and to refuse to rely only upon the reports and testimonials of tourists and delegates. Kelly describes her book as “A Narration in Seven Parts,” sometimes organized chronologically, but mostly thematic, archival, and methodological in organization.

The first chapter, “The Colonial Calculus of Veracity: Delegations under Erasure and the Desire for Evidentiary Weight” elaborates these problems of evidentiary authority though a careful tracking of the key trope of disbelief and the related imperative of witnessing for oneself in often sympathetic travelers’ accounts. As Kelly understands it, solidarity tourism is a complicated business as “There are Palestinians inviting internationals and leading delegations, Palestinians hosting delegates, Palestinians critiquing international presence, and Palestinians from the diaspora on the delegations themselves. Some Palestinians across Palestine invited tourists to witness the clandestine businesses, alternative farming practices, and daily resistances of the first intifada, and some Palestinians across Palestine resented international presence in their homeland, not only for its potential futility but also for the retribution it brought upon its hosts.”

The next chapter, “Asymmetrical Itineraries: Militarism, Tourism, and Fragmentation under Occupation,” brilliantly assembles interviews with many Palestinian tour guides who have been working as such, initially on often clandestine tours of the West Bank, and then as tourism became permitted by the Israeli government after the Oslo Accords of 1993, as participants in a more lucrative, if still precarious economic and pedagogical enterprise. Ironies abound in the accounts of how Oslo restricted Palestinian movement and led to the loss of even more Palestinian land in the name of ostensible sovereignty and the repeatedly broken promise of a two-state solution. Tour guides are often not able to pass through check points, while their tourists can. Tourists get to see parts of Palestine that Palestinians cannot. Kelly writes: “This professionalization of solidarity tourism, then, employed the language of business, from image branding to marketing, at the same time that it employed the language of liberation—from freedom from occupation to anticolonial resistance. The merging of these two goals—business acumen and liberation from colonial rule— sits uncomfortably together with and lays bare the tensions that continue to animate solidarity tourism in today’s post-Oslo moment.”

“Recitation against Erasure: Planting, Harvesting, and Narrating the Continuities of Displacement” focuses on tourist participation in Palestinian agricultural practices. Here the argument embraces a longer historical arc: “The history of uprooting Palestinian olive trees, alongside fig and almond trees native to the land, predates the establishment of the State of Israel and stretches back as far as 1908. These early Zionist claims to the land came in the form of uprooting native trees and planting forests in their stead that commemorated early Zionist leaders like first Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion who sought to fashion Israel after Europe in the form of a “Switzerland of the Middle East.” Olive harvesting and olive tree planting tours walk tourists through this history, using the olive tree as an object that tourists can grasp that can bear the narrative weight of generations of dispossession.” The olive tree is hardly an olive branch here. Kelly notes: “Whether uprooted by military orders, uprooted to make way for the Wall, or destroyed because of settler violence condoned by the Israeli state, the 800,000 olive trees that have been uprooted since 1967, with a loss of $55 million to the Palestinian economy per year, are attacks against Palestinian viability that are sanctioned by the State of Israel and part of the continuity of Israeli colonial occupation.

The book’s focus then moves to Jerusalem “as a city under manifold forms of military occupation, and positioning decolonial tourism as a form of creative, albeit fraught, intervention in the narrative Israel sells about Jerusalem . . . to show how Israel has consistently sought to isolate Palestinians in Jerusalem and hasten their departure from the city and to study the work tour guides are doing to anchor Palestinian businesses in the city and wrest back the narrative of the city from Israeli control.” The chapter shows how solidarity tours negotiate diverging sites and scenes of occupation from the mansions of affluent Palestinians in West Jerusalem now occupied by Israelis after the Palestinians fled or were expelled in 1948 to the Old City where Israeli archaeological excavations encroach on Palestinian streets and threaten to strangle Palestinian businesses, and to East Jerusalem where land is under considerable pressure from expanding Israeli settlement.The next chapter hinges to imaginings of the future that do not seek to obliterate the past. “Colonial Ruins and a Decolonized Future: Witnessing and Return in Historic Palestine” describes tourists “traversing landscapes of rubble from razed Palestinian homes amid donor-funded Israeli forests of cypress and fir, cityscapes of segregation inside Israel’s borders, and appropriated Palestinian villages as Israeli spaces of culture and recreation.” Tourism goes digital in this and the following chapter. The Israeli NGO, Zochrot, (Hebrew for Remembering) responds to the erasure of Palestinian

narratives with an app—iNakba—that with the clicking of a link on a map provides users with an archive of the names and brief histories of Palestinian villages and remembrances from displaced 1948 refugees “to remind Jewish Israeli audiences of what has happened on the ground on which they walk, and imagine a future of reparation in Palestine/Israel.”

‘“Welcome to Gaza’: On the Politics of Invitation and the Right to Tourism” shows how virtual collaborative projects critique and reimagine tourism as both part of a colonizing imaginary and as a possible invitation to a different kind of future. “Through virtual tours that simultaneously describe suffering and create joy, Palestinians in Gaza are combating not only the siege but also the representations of themselves as under siege and nothing more.”

In the final chapter, “Witnesses in Palestine: Imperfect Analogies, Acts of Translation, and Refusals to Perform,” we get the witness as comparative historiographer with attendant possibilities and perils. Kelly writes: “Writer Alice Walker, for example, described the situation in Palestine as “more brutal” than the Jim Crow South. Similarly, historian Robin D. G. Kelley, after a tour organized by the US Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (usacbi), described witnessing in Palestine as “a level of racist violence [he] had never seen growing up as a Black person in the States.” . . . Achille Mbembe describes Palestine as worse than the South African Bantustans, far more lethal than apartheid South Africa, and approximating a “high-tech Jim Crow cum Apartheid.” Solidarity may require comparison, but specificity may be a casualty. It is to the author’s credit that she never lets witnessing stand in as “alibi for research.”

Kelly concludes her book with the exhortation: “in the context of Palestine, where “intractable” peppers the vocabulary as much as “conflict” does, refusing narratives of peace that sediment dispossession, insisting on a tourism that centers decolonization, and demanding the impossible are necessary interventions.”

Invited to Witness: Solidarity Tourism Across Occupied Palestine is an exemplary work of cultural studies that is attuned to deep history and sometimes cursory visitors, that treats solidarity tourism with nuanced ambivalence. The book is obviously of interest to scholars and readers interested in Palestine specifically and settler-colonialism and indigeneity more generally, and readers invested in the ethics and politics of both solidarity and tourism. While the literature of the critique of humanitarianism and human rights is not explicitly engaged, Kelly’s book speaks powerfully to both the pitfalls and the enabling violation of imperial benevolence, even in its insurgent mode.