Omar Kasmani

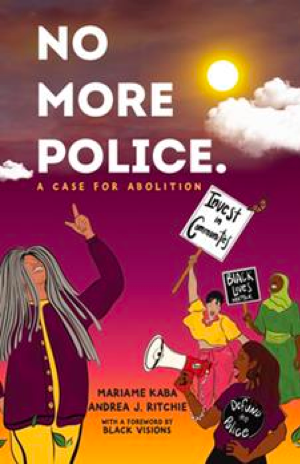

No More Police: A Case for Abolition

Duke University Press, 2022

416 pages

$15.99

Reviewed by Etyelle Pinheiro de Araujo

With every passing year, an increasing number of people—most of them Black —become victims of state-sanctioned violence in the United States. In No More Police: A Case for Abolition, Mariame Kaba and Andrea J. Ritchieconsider different strategies to uproot such systemic brutality while also furthering an entirely new understanding of safety. The book’s opening interpellation, “When was the moment you first started to question the violence of policing?,” is followed by a reminder that each generation produces its own narratives to describe how certain groups of society (namely, subaltern groups such as Black populations, women, immigrants or LGBTQIA+ communities) respond to the fact that the police, rather than preventing violence, are often the ones to perpetrate it. Examining what can be done to break this cycle, the book makes a case for the abolition of police and the relocation of funding to “community-led health and safety strategies.” At first, investments would be channeled into initiatives which seek to amplify access to basic human rights (health, education, housing, leisure); subsequently, groups would be organized in which members of civil society would be tasked with handling non-criminal issues currently under police jurisdiction, such as traffic management and the preservation of public order.

The book begins by recalling the demonstrations triggered by the murder of George Floyd, many of which called for police abolition, as well as by foregrounding the experiences of abolitionist movements such as INCITE!, “a group of radical feminists of color dedicated to ending violence in all its forms.” From a theoretical standpoint, Kaba and Ritchie identify as Black feminist abolitionists aligned with authors such as Angela Davis—who maintains that “the vast experiment to disappear the major social problems of our time relies on racialized assumptions of criminality”—, as well as Ruth Wilson Gilmore, who sustains that “increased investment in police and prisons in the US serves as a mechanism for racial capitalism to save itself from crises of its own creation.” According to the authors, given that the police must operate in the service of capitalism and in protection of private property, they are necessarily incapable of promoting safety for all.

Over the course of nine chapters, the authors—redundantly at times—emphasize the need to abolish the police. Their argument is illustrated by a discussion of how police departments, despite enjoying considerable funding and credibility, often fail to guarantee safety. At the same time, the book argues that there is no “fixed roadmap to abolition;” rather, we must “spend time imagining, strategizing, and practicing other futures.” The writers mention that abolitionists are often criticized for their stance vis-à-vis sexual offenders. The question of how society prevents or responds to sex crimes, while crucial, remains largely unanswered; the authors could perhaps have addressed this issue a bit more at length.

In the first chapter, Kaba and Ritchie provide statistical data to corroborate the thesis that the police, rather than curbing violence, produce more of it, often targeting marginalized groups whose members are not seen as “ideal victims.” Another key argument is that “even though the US spends over $100 billion a year on policing, [it] continues to experience some of the highest rates of violence across all industrialized countries.” In short, it is suggested that large-scale investments in police forces do not produce greater safety.

In Chapter Two, the authors explain how survivors from marginalized groups seldom report the violence they suffer. Reasons include the difficulties in establishing credibility, the unwillingness to impose legal consequences upon perpetrators, and the fear of police-inflicted violence. Many survivors view the police force as a threat: an instrument of retaliation and criminalization which often targets themselves or others in their communities. Hence the need to dispute statistical data suggesting that larger police funding leads to a reduction in domestic violence: a large number of cases, the authors argue, are not even reported.In the following chapter, named “Re-form,” Kaba and Ritchie consider the argument that structural reforms

may trigger a decline in state-sanctioned violence. They argue that such measures are unlikely to produce the desired outcome: over the past two decades, while a number of reforms have taken place—including heavy training and the incorporation of surveillance equipment— instances of police brutality remain widespread. Chapter Four surveys a number of cases in which police reforms appear to be producing a form of “soft policing.” The authors consider whether such interventions are truly conducive to change, or whether they simply perpetuate violence against marginalized groups—because for them, soft policing doesn’t replace the actual police, who are engaged in the enforcement of social policy through their presence in schools, hospitals, and welfare offices, and in policing youth, disabled and unhoused people, and families.

Chapter Five argues that, in addition to defunding the police, changes in attitude are required to materialize “a police-free future” that might include removing police forces from the management of mental health crises, school conflicts, traffic-related issues, and disagreements between neighbors. Change is necessary in how society conceptualizes safety, a notion historically seen as inextricable from the police apparatus. An understanding of safety as a product of social relations may increase the acceptance of abolitionist ideas. In Chapter Six, Kaba and Ritchie discuss the tensions inherent to the abolitionist project, which they regard as a collective endeavor. The crux of these tensions is expressed in the following question: “As abolitionists, how do we get from where we are to the society we want to create while avoiding the pitfalls along the way?”

Abolitionist efforts, they claim, require social engagement and demand that communities call the capitalist paradigm into question, denounce mass incarceration, and work to obtain State resources. Chapter Seven outlines a series of actions oriented towards police abolition. Across the US, they say, organizers “are deploying a multitude of tools to help people imagine and enact that vision through community surveys and engagement, participatory budgeting, and People’s Movement Assemblies.” The authors argue that all such initiatives are underpinned by a desire to practice mutual aid and engage in transformative justice. As examples, they describe how individuals and community groups across the country are working to build and strengthen community relationships and infrastructure to create safety without cops on many levels—at the building, block, neighborhood and city levels, like the Harm Free Zone formal structure.

In the last chapter, the book situates the debate on police abolition in relation to the principles of Black feminism, here approached as a theory of liberation. The writers assert that we must shift our expectations regarding police and, in particular, denounce how police actions affect marginalized groups. Kaba and Ritchie believe citizens are ultimately responsible for enacting effective change.

No More Police, in the authors’ own words, is “a book for people who are engaged in movements to defund police and abolish the Prison Industrial Complex—and for those who want to learn about them.” It is, first and foremost, an invitation to reflect on the police apparatus, and on the groups that benefit from and those that experience more violence because of it. Such reflections, which constitute a steppingstone towards meaningful social change, are especially relevant now, when instances of police brutality and human rights violations have become all too common in the US.