Janine Barchas

The Lost Books of Jane Austen

Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019

304 pages

$35.00

Reviewed by Emma Hetrick

In The Lost Books of Jane Austen, Janine Barchas, an English professor at the University of Texas at Austin, writes about nineteenth- and twentieth-century copies of Jane Austen’s novels that had low production costs and were marketed to working- and middle-class readers. This analysis calls into question the privilege first editions and prominent printings of Austen receive in rare book libraries, advocating for due attention given to the books that helped Austen become one of the most popular British authors even today.

Barchas’s methodology, which she describes as “hardcore bibliography with the tactics of the Antiques Roadshow,” begins by finding ‘lost books,’ a term coined by Barchas to describe the “books bought and read by ordinary people,” primarily from private collections and online selling platforms. Emphasizing their materiality, Barchas uses the construction of each book, including its binding, plates, and paratext, to tell a story of the book’s construction and how its publication history reflects the way the public engaged with Austen at the time of its production.

Each chapter begins with a vignette where Barchas introduces one of the numerous copies of Austen’s novels included in The Lost Books of Jane Austen, along with the novel’s former occupant, who has left some form of written ownership in the book’s pages. Referencing numerous historical sources like census data and legal cases, Barchas paints a picture of who the owner was. She conjectures how they may have come to own the book and what it would have meant to them. Although The Lost Books of Jane Austen is firmly rooted in the field of book history, in the vignettes, Barchas takes the opportunity to reflect on similarities between the owners and the contents of their books, as in the case of Emma Morris, an owner of Emma, who, like the novel’s heroine did not have a living mother.

The first chapter of The Lost Books of Jane Austen chronicles the origins of the earliest paperbacks of Austen’s novels. Barchas argues that these copies were “among the earliest experiments in mass-market paperbacks” and that they “prove how her [Austen’s] entrance into the literary canon occurred in a much cruder fashion than most of her fans today imagine.” Sections in this chapter reveal the importance of Austen’s early British publishers, like Simms & M’Intyre, in popularizing her work by using sensationalist marketing tactics that appealed to everyday readers.

Chapter Two, “Sense, Sensibility, and Soap,” covers the 1890s marketing campaign of soap manufacturer Lever Brothers, in which they gave away copies of Austen’s novels as prizes. The chapter expands into a discussion of how the novels were used in promotional materials and as giveaways more generally. Barchas’s research reveals that Lever Brothers shared both plates and ideas about Austen’s novels as desirable rewards with other publishers and organizations, indicating perhaps surprising similarities between businesses, publishers, and educational spaces (private and Sunday schools were other popular places that disseminated Austen’s novels to the public).

“Looking Divine: Wrapping Austen in the Religious,” the third chapter in The Lost Books of Jane Austen, describes editions of Austen’s work designed to resemble Christian texts like the Bible and prayer books in various contexts. Though they may have had the marks of religious texts, like illuminated bindings and rubricated title pages, Barchas argues that the packaging of these books “yields a radical rather than a conservative product, aiming to capture readers outside the mainstream.” Of course, Austen’s intentions in writing her novels were not to engage in religious instruction. Nonetheless, Publishers and distribution companies invoked religious texts for commercial purposes, as well as to promote education and reformist causes.

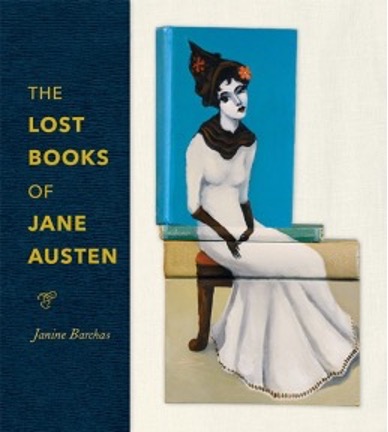

In Chapter Four, “Selling with Paintings: A Curious History of the Cheap Prestige Reprint,” Barchas considers a series of American editions of Austen’s novels that featured illustrations on their covers. By tracing the publication history of these editions, Barchas disputes the idea that Austen was as steadily popular over the nineteenth century in America as she was in England. The focus on artwork and appearance in Austen’s works is mirrored in the composition of The Lost Books of Jane Austen itself. The front cover depicts an original piece of artwork using Austen’s novels, and the text is amply accompanied by images of the novels discussed within.

Chapter Five, “Pinking Jane Austen: The Turn to ‘Chick Lit,’” offers a commentary on how reading Austen’s novels came to be gendered. Though Austen was (and continues to be) read by people of different genders, Barchas argues that cheap reprints of Austen’s novels in the twentieth century were often marketed to young women. Examples include 1960s paperbacks marketed to female college students, Spanish editions meant to evoke connections to the popular escapist romance novel, and copies read by women on the home front and men involved in World War I & II.

The Lost Books of Jane Austen takes readers on a journey across countries, centuries, publishers, and households. Barchas demonstrates that Austen’s rise to literary stardom was far less rapid, straightforward, and assured than originally surmised. She also challenges traditional collecting methods of academic institutions and reading rooms. In doing so, she challenges the very nature of literary and bibliographic research, arguing for a more democratic practice that treasures the more ‘common’ editions of Austin’s novels as much as their first edition counterparts, if not more so. The Lost Books of Jane Austen concludes with a call to action that highlights its wide relevance to various groups: to those in the cultural heritage sector who determine which books their institution acquires, as well as those who conduct research about Austen’s novels, and to anyone reading who may have a copy of Pride and Prejudice or another of Austen’s novels on their bookshelf. Throughout the book, Barchas effectively appeals to her readers to reconsider the value of the ‘lost’ copies of Austen’s books. She offers plentiful evidence of their worth by revealing more about particular publishing practices, as well as the people who read and owned these novels.