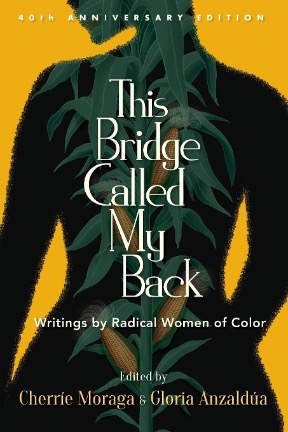

Cherrie Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa

This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color – Fortieth Anniversary Edition

SUNY Press, 2021

286 pages

$34.95

Reviewed by Ricardo Delgado Solis

In 1981, Cherrie Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa compiled and edited several writings from women of color who wrote in opposition to having their political voice historically silenced, neglected, and made invisible within public policies; this enabled them to create a ‘bridge of consciousness’ and amplify their voices. This Bridge Called My Back is an account of US women of color coming to a late 20th-century social consciousness through conflict—familial, institutional—and arriving at a politic, a “theory in the flesh.”

Bridge is an essential text to the modern reader looking to understand women of color’s feminist radical thinking that gave rise to the social consciousness of contemporary Chicana Feminist thought. The first edition of this book, in 1981, opened the doors for Radical Feminism in the Chicano community; forty years later, this new edition still incites hope for revolutionary solidarity among radical women of color. The collection of essays, poems, personal narratives, testimonies, and art of these writers brings awareness to the concerns of race, class, sexuality, and gender that women continue to experience today.

According to Moraga and Anzaldúa, various historical conditions, including the Civil Rights Movement and Chicano Movements, laid the political ground and theoretical framework for US women of color’s feminism in the 1970s, which in turn laid the groundwork for the radical feminist literature and social activism of today. At the time of the first publication, the writers were not white enough for society, nor were they dark enough for their families and communities; economically speaking, they belonged to working-class families. Their sexuality was neither understood nor accepted in society. The combination of their identities forced these writers to search for collective liberation, and the flesh of their experiences was the motivation to create a theoretical radical feminist framework.

“Growing up, I felt that I was an alien from another planet dropped on my mother’s lap.” Anzaldúa refers to this space to explain how she experienced coming to a new consciousness. “We are the queer groups, the people that don’t belong anywhere, not in the dominant world nor completely within our own respective cultures.” Anzaldúa realized that she was not the good Chicanita her mother and culture expected her to be; instead, she was masculine and queer, but also dark, intelligent, brave, something her culture highly despised but made Anzaldúa one of Chicano history’s greatest philosophers and radical feminists. “I see Third World peoples and women not as oppressors but as accomplices to oppression by our unwittingly passing on to our children and our friends the oppressor’s ideologies. I cannot discount the role I play as an accomplice[,] that we all play as accomplices, for we are not screaming loud enough in protest.” Anzaldúa dared to say what everyone was thinking but could not say. Most of her writing throughout the book showcases her poetic and philosophical abilities that inspire hope for those whose voices have stayed silent for the past forty years.

In “La Guera” by Moraga, she explains that she came to consciousness when she understood her reality as a light-skinned Chicana in a brown Chicano world. She acknowledged and confronted her own sexuality, “lesbianism in the flesh,” as she calls it, she came to understand herself as a newly liberated woman from Anglo and conservative family expectations to become one of the most radical feminists of all time; this has made Moraga an icon and legend of Chicana Radical Feminism in the flesh up to this moment. In this new edition, Moraga’s preface serves as an in-depth analysis of the book’s legacy and continues to show why this book has been so successful for the past forty years. She continues to be a living legend as a radical Chicana feminist and an example to follow for those of us who are not brave enough to be radical feminists in our own time.

Without a doubt, This Bridge Calls My Back’s new edition is groundbreaking because the book continues to inspire those of us who also consider radical feminists those who act in solidarity with the most oppressed: women of color. “We see the book as a revolutionary tool falling into the hands of people of all colors. Just as we have been radicalized in the process of compiling this book, we hope it will radicalize others into action. We expect the book to function as a consciousness-raiser, an educator and agitator around issues specific to our oppression as women.” The new edition is the type of book it was envisioned to be. Women of color find a voice of commonality among the Bridge writers. For the past forty years, many intellectuals, scholars, philosophers, and women from all backgrounds have responded positively to this book as a tenet of radical feminism and a must-read for the radical feminist of color. “The Bridge still brings hope for revolutionary solidarity” as it was intended when it was written forty years ago, and it continues to be a feminist “revolutionary tool and a consciousness-raiser.”

In the preface of this new edition, Moraga mentions, “COVID opened our eyes to what we, as people of color, queer and trans, elder and disabled, immigrant and Native, have known all along; the hierarchical structure of privilege in this world determines who gets to live and who dies.” COVID has shown the inequalities that disadvantaged communities of color experience; however, Bridge’s new edition encourages us to be vulnerable and practice social activism to create solidarity with those oppressed in developing countries affected by wars. Moraga points out, “Racism, structurally executed through patriarchy, is the unredeemable and tragic cost of colonization.” Being a radical feminist implies making those around us uncomfortable about fighting against the longstanding postcolonial and neocolonial order of the world. This book is precious as it provides another window to reflect on the manifestations of racial tensions, misogyny, homophobia, and sexism. The letters, poems, essays, art pieces, and philosophical reflections of Bridge have been, and continue to be, words of wisdom and comfort for women of color at a loss given our social reality.