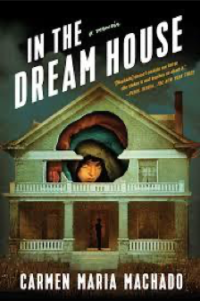

Carmen Maria Machado

In the Dream House: A Memoir

Greywolf Press, 2019

247 pages

$26.00

Reviewed by Camila Torres Castro

“You pile up associations the way you pile up bricks. Memory itself is a form of architecture.”

Cuban American author Carmen Maria Machado starts her third book, In the Dream House: A Memoir, with this quote from renowned artist Louise Bourgeois. Epigraphs have the possibility of foretelling the path a text will take; in Machado’s Dream House, memory and architecture serve as foundations for the scenario she is trying to rebuild. The book is an exploration of the author’s own abusive relationship with another woman, one that starts on an idyllic note and becomes a deep fog that invades every space of the eponymous house. Machado twists genres in order to tell a brimful yet coherent tale that sheds light on the reality of violent relationships.

Carmen Maria Machado was shortlisted for the US National Book Award in 2017 for her anthology of short stories, Her Body and Other Parties. The eerie atmosphere that characterizes said collection seeps into this memoir, effectively positioning Machado as a master of the gothic. In her memoir, body and house get interwoven in a power dynamic that displaces her from her own self-control. The result is a terrifying aura that resembles Dario Argento’s body horror in Suspiria, where it seems that the very thing you desire most is out to get you. With In the Dream House, Machado’s arc as an author so far becomes evident: bodies, the built environment and an ingenious darkness surround her narration and exploits traditional fiction to evoke the real.

In the Dream House is divided into small chapters that resemble exercises of style. One chapter lets you choose your own adventure, another is a made-up story about a squid and queen, and so on. Each chapter showcases a different aspect of the relationship’s course, whether it be a particular moment or an event from her past that somehow resonates with the present. Machado’s virtue, however, is that it makes sense. There is a candid effort to demonstrate the many shapes that violence can take and how differently it can be perceived, articulating the things that can’t be said through fictional tropes. If anything, this memoir is living proof that forma es fondo. The structure of each chapter is a medium that allows her to dissect the intangibility of certain forms of abuse. While some are clear (the cruel words, fingers digging into soft skin) others are more subtle (a sharp look, the inferred tone of a text). Through her witty, raw prose and the cartography of the text it becomes clear that the dream house is nightmarish.

Machado’s prose feels like many doors are opening all at once. In a way, that is what she does by using a number of literary tropes to construct a story that at times seems fragmented. Probably that is the point: a series of small nightmares that together become a dark dreamscape. This is how she builds the dream house and simultaneously constructs an archive through ephemera, effectively channeling late José Esteban Muñoz’s ideas into a creative exercise. Machado points out how difficult it is to prove the existence of abuse when there is no physical evidence: no actual bruises, no saved pictures or texts, no broken glass anywhere to be found. This dreamscape exposes the lack of an archive that illustrates domestic abuse in queer relationships, a space that has been otherwise regarded as a wonderland that violence can’t pollute. There is also a declaration of principles in this book, one that underlines the importance of having conversations about how gay relationships can also fall into violent dynamics that are usually tied only to heteronormativity. What makes domestic abuse so parasitic is its ability to mutate and adapt to any circumstance.

Unlike other memoirs, In the Dream House does not quite follow a linear timeline. It is hard to pinpoint when Machado’s relationship turned upside down. The build-up is not as visible as one would think. There is no dramatic tension that eventually leads up to an explosion. But maybe this is because domestic violence (and life itself) is like that: it does not respond to a bigger script; it does not stick to a particular narrative trajectory. It is not a movie or a fairy tale. It happens. Was the bad always there? It is not entirely clear. Violence seems to come in waves: right after an abusive episode there is a moment of calm. It all sounds distorted, almost absurd if we think that the abuser is, paradoxically, the one that brings comfort as well.