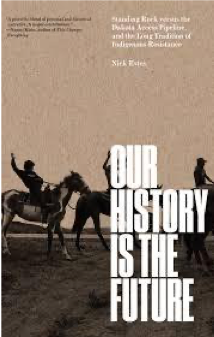

Nick Estes

Our History is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance

Verso, 2019

320 pages

$26.95

Reviewed by Annie Bares

Our History is the Future begins and ends with scenes of radical struggle and of possibility at Oceti Sakowin, the largest of several camps formed near the Standing Rock Reservation from 2016-2017 in opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline. Estes, who is a citizen of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe and an Assistant Professor of American Studies at the University of New Mexico, participated in the activism and analysis that came to be associated with Water Protectors. However, as Estes reiterates throughout Our History is the Future, Water Protectors “weren’t simply against a pipeline; they also stood for something greater: the continuation of life on a planet ravaged by capitalism.” Taking #NODAPL and Mni Wiconi (“water is life”) as its animating premises, Our History is the Future chronicles the long history of Indigenous resistance to settler colonialism.

Part history, part work of contemporary political analysis, part collective memoir, and part manifesto, Our History is the Future narrates various scenes of violence and Indigenous resistance that arise in their wake in what came to be known as the United States. Estes’s style and the book’s non-linear structure emphasize the circularity of these histories, disrupting traditional narratives of incremental, progressive social change. Each of the book’s seven chapters weaves together histories of Indigenous oppression and resistance with scenes from the present and implications for the future. In doing so, the book resists settler-colonial chronology, instead structuring its narrative in keeping with Indigenous revolutionary epistemologies that “aim to change the colonial present, and to imagine a decolonial future by reconnecting to Indigenous places and histories.”

Grounded in Indigenous (particularly Lakota) understandings of relationality, Estes theorizes what he refers to as “the tradition of Indigenous resistance.” Estes defines Indigenous resistance as accumulation, “one that is not always spectacular, nor instantaneous, but that nevertheless makes the endgame of elimination an impossibility: the tradition of Indigenous resistance.” Indigenous resistance is both a “radical consciousness and political practice” that persists in spite of the slow violence of environmental racism, extraction, and warfare. Estes centers Indigenous epistemologies, cosmologies, and practices of relationality, both amongst humans and between humans and “other-than-human kin,”—Estes’s term for nature, animals, and other matter—as both historical and future-oriented sites of anti-colonial struggle.

Our History is the Future begins with Estes’s account of his experience at Standing Rock conceived of as a prophecy that diagnoses the condition of the present and aims to shape the future. From there follows “Siege,” a chapter on the conditions of extractive racial capitalism, militarization, and dispossession that culminated in #NODAPL. Estes traces these conditions of the present to forms of violence, warfare, and dispossession rehearsed in early encounters between European settlers and Indigenous people. “Origins” connects contemporary oil extraction to early histories of settler-colonialism’s violent project to extract natural resources from Indigenous nations and to spread capitalism and its ideologies of private property and individualism.

In “War” and “Flood,” Estes uses the history of late nineteenth- and twentieth-century policies of the U.S. toward Indigenous nations to reframe the notion of historical agency. Key to his argument is that unlike settler-colonial or liberal humanist understandings of sovereignty, Indigenous people are “sovereign nations—not simply cultures” or individuals. In “War” he contends that “the founding of the United States was a declaration of war on Indigenous peoples.” He describes how the forceful imposition of capitalism onto Indigenous nations, broken legal treaties, enforced individual citizenship, flooding of tribal lands, and supposedly benevolent undertakings like federal ward programs, boarding schools, humanitarian aid, and land management programs degrade Indigenous sovereignty. The final three chapters, “Red Power,” “Internationalism,” and “Liberation” describe twentieth and twenty-first century movements for Indigenous liberation.

In describing how traditions of resistance arose from this state of permanent warfare and the constant threat of genocide, Estes offers a particularly generative analysis of The Ghost Dance and its recurrence across history as an example of an Indigenous strategy for survival in the present that ties history to the future. Arising in the 1880s in the wake of mass dispossession, the formation of reservations that acted like concentration camps, boarding schools, and the near extermination of buffalo herds, The Ghost Dance was a prophecy that foretold the end of the current world, along with the end of settlers, and colonialism at large that would usher in a new existence, marked by renewed relations between humans and other-than-human life. In recounting how The Ghost Dance has been misinterpreted by Western historian and anthropologists and how it has been criminalized by the U.S. government, but has, nonetheless, reappeared throughout U.S. history, including at Standing Rock, Estes demonstrates the extent to which Indigenous liberation and futurity is tied to history.

As the term “Indigenous tradition of resistance,” might suggest, in addition to grounding its analysis Indigenous epistemologies and theories of relationality, Our History is the Future also draws on the Black radical tradition. In particular, Estes cites W.E.B Du Bois, Cedric Robinson, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, and Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, along with the Movement for Black Lives, as interlocutors in relating settler-colonialism to racial capitalism and defining resistance as an ongoing history. In addition to bridging the Indigenous and Black radical traditions, Our History is the Future also intervenes in the environmental humanities in its insistence that Indigenous knowledge of and relation to the natural world has for centuries recognized the agency of other-than-human life. Due to its ambitious historical scope, clear, powerful prose, and emphasis on forms of knowledge that exist beyond traditional academic registers, Our History is the Future would be of interest to broad, public audiences, as well as students and scholars of Indigenous, environmental, and radical history and culture will find it useful.

In delineating the Indigenous radical tradition, Estes argues that while Indigenous resistance is tied to the traumas of colonialism and genocide, it is also rooted in the success of these survival tactics and the forms of collectivity across generations that they gave rise to. Moving beyond frameworks that see “Indigenous peoples as perpetually wounded,” Estes’s accounts of The Ghost Dance, along with the Red Power movement, Indigenous Internationalism, and #NODAPL also emphasize how Indigenous people “formed kinship bonds and constantly recreated and kept intact families, communities, and governance structures” and “how they remain, to this day, the first sovereigns of this land and the oldest political authority.” Estes stakes these claims not in acts of individual agency, but instead in notions of sovereignty that move beyond liberal humanist subjectivities. He uses the organization of the camps near Standing Rock based on principles of care, kinship, and hospitality as evidence of the continuity of Indigenous survival and political power, noting that “it was Indigenous generosity–so often exploited as a weakness that held the camp together.” Even in the wake of the approval to construct the Dakota Access Pipeline, Estes holds that “the fort is falling.” He ends by suggesting that with Indigenous leadership that privileges relationships outside of capitalism, “we are challenged […] to demand the emancipation of earth from capital.”