Jordan Peele

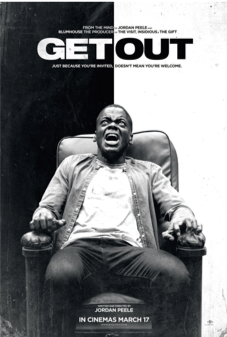

Get Out

Blumhouse Productions, 2017

104 minutes

$14.99

Reviewed by Emma Hetrick

Jordan Peele’s genre-defying 2017 film Get Out masterfully addresses the way Black Americans experience racism, both personally and systemically. A neo-slave narrative that draws elements from horror and sci-fi genres, the film satirically but effectively argues that the United States is far from being a post-racial nation. The film’s opening scene shows a young Black man (Lakeith Stanfield)—whose name the viewer later learns is Andre—walking down a street, expressing discomfort about being in a white, suburban neighborhood. The viewer begins to share Andre’s paranoia when a car slows down, and the paranoia escalates to fear when the driver steps out of the car, knocks Andre out, and puts him in the trunk. From the start, Peele makes clear that at no time in this film—nor more generally, in the U.S.—are Black Americans safe. As the film unfolds, the accumulation of minor interactions between the protagonist Chris (Daniel Kaluuya) and his girlfriend Rose’s (Allison Williams) family members, family friends, and family employees, causes Chris to realize that he is in the middle of an inescapable nightmare that threatens his very selfhood.

The film revolves around a trip Chris and Rose take to visit her parents, Dean and Missy Armitage (Bradley Whitford and Catherine Keener). During Chris’s first night at the Armitages’ home, Missy temporarily hypnotizes him, ostensibly because she caught him smoking—a habit of which she disapproves. The viewer soon realizes Missy’s intentions are more sinister when her hypnosis causes Chris to become immobile and to enter the “sunken place,” an intermediary state of being expressed onscreen as Chris’s consciousness falling through space—while his physical functions, such his ability to see and hear, remain intact. The “sunken place” can be read as an iteration of W.E.B. Du Bois’s concept of “double consciousness,” which refers to how Black Americans see themselves outside of their own bodies and experience the incongruities of being both “Black” and “American.” Peele extends the concept of double consciousness by refocusing his attention back onto the body, examining how systemic racism is expressed through and inscribed upon the very medium of Black bodies. Later in the film, Chris realizes that the other Black people Chris encounters while at the Armitages’, including the family’s house employees—Georgiana and Walter (Betty Gabriel and Marcus Henderson)—and a much-altered Andre, are all in the sunken place, their bodies having been overtaken by white brains transplanted through surgery. When the Armitages host a party, all of the guests are keen on speaking with Chris. Chris becomes more unnerved as the partygoers remark on his appearance and photography skills. As it becomes clear that the purpose of the party is to bid on Chris’s body, there is a sense that the specter of transatlantic slavery continues to haunt the U.S. present in the form of the contemporary desire for the Black body and disregard of the Black mind.

There are, however, moments of rupture in which Georgiana, Walter, and Andre are able to assume control over their bodies. In one of the most poignant scenes of the film, Chris steps away from the party and asks Georgiana if she is bothered by being around so many white people. She emphatically and repeatedly replies “no” while smiling, but her smile is forced, and a tear drops from her eye. Unlike Andre and Walter, who require intervention from Chris in order to break through from the sunken place, Georgiana is able to penetrate the sunken place on her own. This opens up questions that go unexplored in the film, including the extent to which gender plays a role in the characters’ abuse at the hands of the Armitage family.

Bodies and minds are violently separated in Peele’s film. Chris ultimately manages to free himself from the Armitages, escaping the power of Missy’s hypnosis by stuffing his ears with the cotton of the chair into which he’s been strapped. Pointedly, it is Chris’s quick thinking about how to protect his body from Missy’s hypnosis that saves Chris from being possessed. This scene seems to reify the over-valuation of the mind over the body and suggests that Chris’s mind is somehow safeguarded from the effects of racism.

Peele actualizes microaggressions, racism, and white supremacy in Get Out, and in the process forces the white viewer to confront the horrific reality of millions of Americans. Yet, Chris’s escape at the end of the film, and the moments of surfacing by the real “selves” of Georgiana, Andre, and Walter, suggest that the sunken place is not a permanent state of being. Agency exists within and can be transmitted through community-oriented interaction.