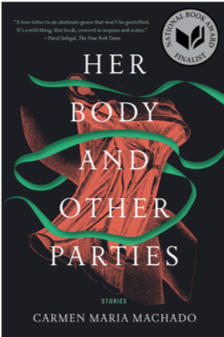

Carmen Maria Machado

Her Body and Other Parties

Graywolf Press

241 pages

$16.00

Reviewed by Bianca Quintanilla

Carmen Maria Machado’s debut short story collection Her Body and Other Parties (2017) explores the myriad sensations of pain and pleasure that women’s bodies undergo. The ambivalence of ‘undergo’ is key here; Machado’s stories are accounts of women’s experiences of the body freely given or forcefully submitted––to lovers, to fraught medical practices, and to sexualized violence. The first story, “The Husband Stitch,” follows an unnamed woman’s sexual relationship with the man that will become her husband. Although the couple enjoys passionate lovemaking, the man begins to exert a dangerous power over the woman’s body after she gives birth. She undergoes a surgery that enhances her husband’s sexual pleasure at the expense of her own. The conflict in their sex life increases until the husband, as if to relieve these tensions, insists on untying the ribbon at his wife’s neck, a ribbon that she was born with and has worn all her life. The woman yields to her husband’s demands, allowing him to untie the ribbon: her head instantly falls from her neck and rolls off the bed, and yet she cannot “blame him even then.”

Elsewhere, Machado pushes generic boundaries to center sexual violence. In “Especially Heinous: 272 Views of SVU: Law &Order,” Machado uses the serial crime drama to comment on the popular representation of harm done to women’s bodies. After a slew of brutal murders and rapes, the narrator notes that “[f]or three days in a row, there is not a single victim in the entire precinct.” During this lull, the typically action-packed SVU episode turns to the domestic lives of detectives Benson and Stabler. Their uneventful off-duty time lacks entertainment, which Machado delivers: she swiftly resumes the brutal crimes she’d held in suspension, demonstrating that a show like SVU is about critiquing, not halting, gendered violence.

In “Real Women Have Bodies,” Machado plays on the 2008 film Real Women Have Curves to recast beauty standards in terms of women’s rights. The women in the story remark on the fact that they are “fading,” losing their embodied form without physically dying. This “fading” is a source of profound anguish for women and their loved ones. The cause of the fading is hinted at obliquely: the women protest their fading by “fucking up servers and ATMs and voting machines,” laying siege to the technological limbs of heteropatriarchy. While “Real Women Have Bodies” represents a widespread loss of embodiment, “Eight Bites,” another story in the collection, explores the individual psychology of societal beauty standards. Here, the protagonist undergoes surgery that reduces one’s appetite to induce weight loss. The voluntary surgery appears at first like the protagonist taking possession of her body, but as the surgeon gets to work, possession seems to change hands: “[h]er hands are in my torso, her fingers searching for something. She is loosening flesh from its casing, slipping around where she’s welcome, talking to a nurse about her vacation to Chile.” Boundaries are blurred between surgeon and patient, between woman and woman, between mind and body, between body and body. The surgeon’s breach of the body, and the intervening conversation, conjures the woman-identified body as something eerily unwhole, un-self-contained, and un-self-possessed.

Although in this collection Machado does not directly address categories such as race or class, neither does she foreclose them. She rarely describes women’s physical features—she describes what is done to women’s bodies, not the bodies themselves. Instead of directly identifying the socioeconomic statuses of her characters, Machado represents these women through their diverse circumstances. For example, the characters in “Real Women Have Bodies” work in factories, jobs that are underpaid and dangerous. In contrast, the protagonist of “Eight Bites” comes from a family in which elective cosmetic surgery is the norm. The varied socioeconomic positions of Machado’s women raise questions about institutional inequality and the ways in which this inequality itself has been instituted in bodies, gender, and sexuality.