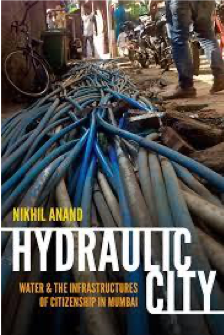

Nikhil Anand

Hydraulic City: Water and the Infrastructures of Citizenship in Mumbai

Duke University Press, 2017

312 pages

$27.95

Reviewed by Molly Porter

In Hydraulic City, Nikhil Anand considers the tenuous structures of citizenship and belonging in the physical and political infrastructures of postcolonial Mumbai. Based on several years of field research, this outstanding anthropological work seeks to better understand the social and legal position of Mumbai’s settlements, Anand’s preferred term for slums. Anand examines the fluctuating relationships that settlers have with the local and state governments in Mumbai and how they’re able to assert their presence and legal right through their access to running water. This new category of citizenship, which the author refers to as hydraulic citizenship, is not easily granted, nor is it guaranteed once recognized by the state. Instead, settlers must constantly negotiate with state and local authorities, with water treatment workers and pump operators, and, ultimately, with each other in order to maintain the water necessary to live and state recognition of their legal presence.

The first two chapters of the book consider the narratives of citizenship in Mumbai and how both the government and the settlers seek to influence and change these narratives. In Chapter One, Anand focuses on the rhetoric and politics surrounding water scarcity in Mumbai. Through close examination, Anand is able to demonstrate that the narratives of water scarcity at once help to dismiss concerns of the inequality of water access and justify diverting water away from other, more rural areas of the country—an act which, in turn, drives people from those areas into the settlements of Mumbai, thus furthering the cycle of scarcity dialogues.

Chapter Two delves more deeply into the complex methods of relation through which settlers interact and establish citizenship, as well as the dependency of the established, more affluent part of the city upon the settlements and their inhabitants. Building on the work of anthropologist Marilyn Strathern, Anand argues that the residents of Mumbai, and especially settlers, are dividuals, “differentially and simultaneously constituted through the discrete exchange of gifts, commodities, and rights, enabled through infrastructure services in the city.” Using the concept of the dividual, Anand effectively traces the development of settler citizenship claims.

In Chapter Three, Anand considers the role of the local government and employees and the ways in which the government uses water schedules not only as a way of distributing water effectively but also as a means of control. Through setting the water schedules for each area of the city, the government is able to mandate the existence of its citizens—and, disproportionately, its settlers—within a temporal framework over which those citizens have no control. While the more established and governmentally recognized areas of the city have stronger water pressure and a water schedule that provides that pressure for a longer period of the day, many settler communities have to share a pipe connection and draw water during a set, three-hour period each day. This necessitates presence and cooperation among the settlers if they want to have enough water for daily life. By curtailing settlers’ access to water, too, the government of Mumbai makes it more difficult for settlers to establish themselves through hydraulic citizenship, either by demanding better access or by moving to a more established area. Anand is also careful to note the gendered expectations of such duties; frequently the women in the family must stay home in order to collect the water during the scheduled times. By judiciously highlighting such disparities within the settler communities, Anand offers a more nuanced view of hydraulic citizenship and its inequalities.

In Chapter Four, Anand considers the lines of communication between the government and the settlers who seek recognition as hydraulic citizens. He describes his time with people he refers to as “social workers” from the group Asha and their efforts to create structural change for the residents of the settlements. On behalf of the settlers they represent, Asha’s workers negotiate the fraught political landscape of life in the settlements, including things like water connections. These workers are also frequently the intermediary between the settlers and the politicians who actually have the power to address issues with the water system and establish new water connections. In helping people to attain hydraulic citizenship, these politicians engage in a system of reciprocity. The workers, many of whom hail from the settlements themselves, work constantly to bridge the gap between the settlements and the various government entities for whom denying hydraulic citizenship might otherwise be advantageous. Anand also deftly illustrates his own position within the settlements; his field work often places him in a position of intervention, and this acute awareness of his own liminality strengthens his argument about the tenuous nature of hydraulic citizenship.

In the last two chapters, Anand turns his attention to the many ways in which the hydraulic infrastructures of the city break down. In Chapter Five, Anand discusses the factors involved in instituting a ‘continuous,’ 24/7 water system in Mumbai and the practical and political difficulties in switching over from the current intermittent system, not the least of which are leaks. Anand notes the many leaks in Mumbai’s water system and considers the causes for the leaks as well as the difficulties in fixing them. He cites a study that “[suggests] that over a third of the city’s water [is] ‘leaking’ both into the ground and to residents drawing water through unauthorized connections.” The water department of Mumbai chose to dismiss the study upon initial publication because of the potential damage to their public image, but behind the scenes, the water department and the local, state, and federal governments all work to address the leaks in the city’s intermittent water supply, even as new leaks appear daily.

In his final chapter, Anand demonstrates the tenuous nature of hydraulic citizenship within the settlements of Mumbai by examining the water connections, or lack thereof, for a subset of the settler community: Muslims, who have been increasingly discriminated against in recent years in Mumbai and in India on a larger scale. Anand focuses on the settlement of Premnagar, a predominantly Muslim settlement in northern Mumbai that previously had adequate water, but now suffers due to an intentional lack of maintenance. The residents are denied hydraulic citizenship and must resort to creating unauthorized connections in the pipe systems and leading to the leaks outlined earlier or digging bore wells to access groundwater, an option that is usually less sanitary for residents. Anand outlines the ways that the disenfranchised Muslim residents of Premnagar access water outside of the government’s purview, and he underscores the need to examine the “brazen attempts” to control water, an element prone to leaking and slipping away.

In what is ultimately the central focus of the book, Anand highlights the dichotomies of authorized versus unauthorized connections and settlers versus established citizens in order to emphasize the codependence inherent in these relationships. Further, he underscores the futility in attempting to control water, itself of a materiality so resistant to control, as well as the use of water to control others—attempts that inevitably lead to leaks. Finally, Anand throws into sharp relief not only the class disparities but also the religious and gender disparities in the interactions and behaviors necessary for sustained hydraulic citizenship. For those in the fields of anthropology, geography, infrastructure studies, science and technology studies, and postcolonial theory, Hydraulic City offers a cogent and comprehensive study of the tenuous boundaries of citizenship and belonging in contemporary Mumbai.