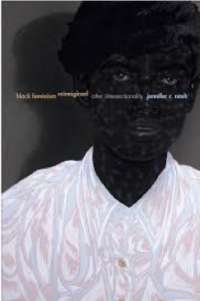

Jennifer C. Nash

Black Feminisms Reimagined: After Intersectionality

Duke University Press, 2019

170 pages

$24.95

Reviewed by Diana Silveira Leite

In her second book, Black Feminisms Reimagined, Jennifer C. Nash examines the complex institutional and intellectual history of black feminisms in the age of what she calls “the intersectionality wars” and proposes an armistice through affect theory, particularly through the concepts of care and a call for “faithful reading.” She locates her project in US universities, particularly the field of women’s studies, where, she argues, the affect of “defensiveness” has “come to mark contemporary academic black feminist practice.” She attends particularly to the institutional life of intersectionality, as it has become the “ethical orientation” of women’s studies programs, even as the theoretical framework of intersectionality turned out to be largely disregarded as an analytical tool. Here,Nash positions intersectionality at the epicenter of the fraught relationship between women’s studies academic institutions and black feminists. Black Feminisms Reimagined is particularly concerned with the semantic erasure of the term “intersectionality.” According to Nash, as the general concept transcended academia and entered popular discourse, intersectionality became “emptied of specific meaning.” Nash suggests that women’s studies programs are currently engaging in “intersectionality wars,” which she traces in relation to the “sex wars” of the 1980s, during which feminist scholars became polarized along the issue of sexual pleasure and its dangers. The “intersectionality wars,” as Nash proposes, are not battles over sexual culture (and its censorship), but over the following question: “will black women ‘save’ so-called white feminists with an insistence on intersectionality as the analytic that will free feminism from its exclusionary past and present?”

Nash’s institutional theory hinges on black feminists’ “defensive position” and their role as analytical “disciplinarians” of intersectionality. This theory proposes that, through “defensiveness,” black feminists become stewards of intersectionality “as territory that must be guarded and protected through the requisite black feminist vigilance.” Instead of the affect of defensiveness, or “holding on,” Nash elaborates a relationship between black feminist theorists and their intersectional praxis that liberates scholars from this defensive position, which she considers a hinderance to black feminism’s “visionary world-making capacities.” Nash posits that the “larger project of [her] book is to practice an ethic of letting go and to disrupt the claims of territoriality and defensiveness that…have come to animate black feminist academic practice.” Nash believes that the unravelling of black feminism from its defensive position will allow for an expansive and generative understanding of intersectionality. Chapter One, “A Love Letter from a Critic,” explores the possibilities for an affective relationship between “we—black feminists” and intersectionality’s critics. She unironically suggests that black feminists consider such critics as “figures who lovingly address,” as a way to foster black feminism’s work-making potential.

Black Feminisms Reimagined is particularly concerned with the slippages between intersectionality, black feminism and black women. Nash describes such slippages as moments when these three distinct concepts—intersectionality as a theory, black feminism as a field of study, and black women as individuals—become conflated. According to Nash, this careless construction halts discussions of intersectionality’s limits and possibilities, as critiquing intersectionality becomes synonymous with opposing black feminism’s field of study and black women’s bodies. This conflation is particularly significant with regard to the suggestion that that “criticism is a violent practice,” one that Nash wishes to dismantle. In this context, any criticism—that is, violence—against intersectionality would imply violence against black feminists and black women’s bodies. Nash notes that the language used to describe intersectionality’s critics is often one of violence, “disappearing, commodification, colonization…” In this context, US universities in general and women’s studies in particular become the site of a Manichean debate over the meaning and generative power of intersectionality as an analytical tool. “Black feminists” become its defenders, and “critics” its destroyers. While Nash maintains that scholars have raised important questions about intersectionality and its limits, she recognizes that criticism is the law of the land in academia. Institutional practices and the pressure to publish reward dissent rather than generative discussion. The result of this confrontational environment is black feminists’ “defensive position.” Nash notes that she occupies both these positions as “a scholar invested in a robust black feminist theory” and “a scholar whose name is often included in the list of ‘critics.’” Her claim, therefore, is for a generative relationship between these two positions, instead of an endless tug-of-war for the future of intersectionality. For Nash, the critic of intersectionality does not simply herald the doom of intersectionality, but proposes new directions and “other ways to be and feel black feminist.”

In Chapter Two, “The Politics of Reading,” and Chapter Four, “Love in the Time of Death,” Nash engages with Christina Sharpe’s concept of “wake work,” particularly as it relates to care. Wake work, according to Sharpe, provides a way to think care as generating meaning for “Black non/being in the world.” Nash aptly notes that care is an affective practice deeply rooted in loss and/or loss avoidance, particularly in the context of Black non/being. This care, she notes, is particularly relevant as it generates strategies of “resisting antiblack sexist violence.” She warns, however, that “care, love, and affection” may also “mask a pernicious possessiveness” and a refusal to let go, to allow intersectionality to “move and transform in unexpected and perhaps challenging ways.” Nash also engages with Sharpe’s “wake work” in relation to her conception of “black feminist love-politics,” which she relates to two key commitments, “mutual vulnerability,” a strategy for mutual dependency and survival, and “witnessing,” the naming of the daily violence perpetrated against black women. Witnessing, Nash notes, builds on “wake work” as part of black feminists’ engagement with survival.

Despite—or perhaps because of—Nash’s engagement with afropessimism and Sharpe’s theorization of Black non/being, “Love in the Time of Death” ends with a call for a black feminism “rooted in love rather than territoriality and defensiveness.” For Nash, the strategy of “letting go” of intersectionality provides a risky avenue for the evolution of its analytical potentials. But the risk is worth taking, since letting go presents the only way forward for intersectionality, allowing for the creation of new possibilities for black feminism beyond territoriality. Black Feminisms Reimagined ultimately argues for a more diverse and dynamic form of intersectionality through the revival of “the notion of ‘women of color’” and renewed “connections between transnationalism and intersectionality.”