Hershini Bhana Young

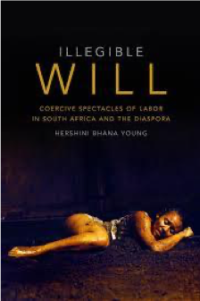

Illegible Will: Coercive Spectacles of Labor in South Africa and the Diaspora

Duke University Press, 2017

280 pages

$26.95

Reviewed by Joshua Kamau Reason

Illegible Will: Coercive Spectacles of Labor in South Africa and the Diaspora is a performative reading of the colonial archive that traces Black women’s assertion of will (and its effacement) in South Africa and throughout the African Diaspora. Indebted to the work of scholars such as Saidiya Hartman, Diana Taylor, Joseph Roach, and Rosemarie Garland Thompson, Young conceptualizes Black women’s acts of refusal as “a diasporic repertoire of shifting creative and embodied responses to imperialism that exceed the textual and the verbal.” The introduction sets the stage for the larger work with a number of assertions, including the affirmation of Black performance as knowledge production, the corporeality of the Black body, diasporic contacts throughout the Black Atlantic, and the institutionalization of sexual violence during chattel slavery. The central purpose of her monograph is to make “(black) will” legible through “performative critical engagements with absence” in the historical archive, interrogating how Black women are remembered in post-apartheid South Africa by centering the deviant, non-normative, unintelligible Black body in her analysis.

Each chapter of the book analyzes a performance, novel, or historical narrative that, in the absence of direct acknowledgement, presents the will of Black women. Chapter One problematizes the repatriation of Saartjie (Sarah) Baartman’s remains to South Africa, arguing that the event was a symbolic articulation of post-apartheid nationalism rather than an act of justice and reverence for the dead. Chapter Two considers the murder trial of Tryntjie of Madagascar as an example of performative ritual, an act that, in lieu of gaining justice for the enslaved, “cement[s] the link between an increasingly racialized slave agency and criminality.” In Chapter Three, Young reads an Angolan beauty pageant for landmine victims as a “performative spectacle” in which Black disability is evoked to obscure the lines between coercion and consent. Chapter Four examines a variety of South African literature to explore the racial-gendered-sexual dimensions of labor within South Africa, promoting “a more nuanced discussion of free and unfree labor that centers on questions of will.” To conclude, Young uses Chapter Five to unpack the harrowing tale of Sila van der Kaap, as told in the historical novel by Yvette Christianse, by offering performative vulnerability as a corrective to unsympathetic readings of Black women’s choices around life and death.

Young’s monograph contributes to our understandings of Black will, slavery, and the transmission of historical knowledge by centering Black performance in her work. As with Diana Taylor, Young defines performance broadly both as onstage and quotidian forms of embodiment, arguing that fictional accounts can have as much to offer us as the colonial archive. Her refusal to give up on enslaved Black women and girls, similar to Saidiya Hartman’s Venus in Two Acts (2008) and Omise’eke Tinsley’s Black Atlantic, Queer Atlantic (2008), presents new possibilities for not only knowing Black women’s histories, but also their assertions of will in the face of colonial domination. More than a compilation of literary texts and case studies, Illegible Will is a reflection on the erasure of Black women’s will, the mechanisms of domination that facilitate this erasure, and the repertoire of actions and gestures that allow us to know how they might have resisted these impositions on their freedom.

With the growing body of literature on the afterlives of slavery, Young provides a timely analysis of racialization, labor, and relationality between colonial subjects. In lieu of drawing false equivalencies between transatlantic slavery and Indian indenture, Young positions them as concomitant histories that can tell us more about “imperial labor schemes” in South Africa. In exploring how colonial contacts (between oceans and peoples) shape embodied practices of will, Young opens a nuanced conversation about imperial legacies that honors the specificity of ethnoracial experiences without the romanticization of “belonging through suffering.” Her take on the afterlife of slavery grapples with both Afro-pessimism and critical race theory by cross-reading, rather than subsuming or essentializing, the overlapping histories of non-consensual labor in South Africa.

The discussion of death (by suicide, murder, and more) throughout Illegible Will also complicates discourses on slave agency and necropolitics in Black studies. Young argues that, in contrast to the repertoire of willful practices that she assembles throughout the chapters, suicide “obscured the quotidian violence of plantation labor.” Rather than a release from the conditions of chattel slavery, suicide represented a slow death that both preceded and exceeded the event of the suicide itself; even in death, the body performed the coercive labor of serving as spectacle to disincentivize other slaves from killing themselves. Young’s discussion of mothers who killed their children provides a similar take on murder and suicide. When we attend to the physical and psychological atrocities committed under chattel slavery, it becomes understandable that an enslaved woman would attempt to take her life, and the lives of those whom she loves, into her own hands. By analyzing the historical conditions under which enslaved people committed suicide and murdered their kin, Young encourages the reader to engage the repetitious acts of violence that produced these deaths, for attending solely to the event elides the subjectivities and desires for freedom that enslaved people enacted whenever and however possible.

An interdisciplinary work that reimagines Black freedom, Illegible Will leverages Black performance studies to think through the silences of the colonial archive around Black women’s assertions of will. Young’s expert examination of Black women’s relationships to labor, nationalism, and imperialism make this work a key contribution to the fields of performance studies, Black studies, history, and decolonial thought. Furthermore, Young provides a theoretical framework for understanding not only the histories of Black women, but those of Black LGBTQ+ folks, Black disabled persons, and other diasporic subjects who exceed the limits of formal histories. Illegible Will is another phase in the ongoing project of dissident knowledge production that centers new ways of knowing those communities who were never meant to survive, be found, or live beyond that which was ascribed to them in the annals of colonial history.