Daina Ramey Berry

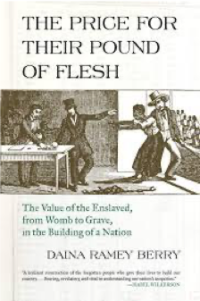

The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved, from Womb to Grave, in the Building of a Nation

Beacon Press, 2017 282 pages

$18.00

Reviewed by Joshua G. Ortiz Baco

As with many economic histories of slavery, terms like sale, appraisal, and value appear throughout The Price for their Pound of Flesh. Daina Ramey Berry, however, proposes a rearrangement of our understanding of familiar terms and figures. Berry organizes her chapters “around the life cycle of an enslaved person’s body” and not within the chronological order often used to explain the development of slavery in the United States. In a clear contrast to trends like cliometrics, interpretation guided by big-scale statistical analysis, the book diverges from accepting fiscal values literally or utilizing a macro analysis to understand individual elements in the lives of the enslaved. Rather, the appraisal and sale price ranges that appear at the beginning of each chapter become a starting point to probe the values assigned to each individual presented in the book, generating questions that the official record leaves unanswered. As the title suggests, the six chapters cover the justifications used to monetize human beings before they were born and long after they had passed away. Berry presents these justifications but overlays them with a keen awareness of the moments that reveal how the enslaved valued themselves.

Often buried in the record of the enslavers or cast aside as unverifiable details, voices of the freed and enslaved Blacks in the archive are reintroduced by the author’s demonstration of the possible correlations between the internal and the external values attributed to their bodies. That is to say, the appraisal price based on future production, the sale price determined by the market, and the ‘ghost value’ conferred at the time of death are external metrics which are influenced by the internal qualities Berry terms ‘spirit’ or ‘soul value.’ This last concept, coined by Berry, is inferred from an array of actions by the enslaved that affirmed their personhood. In the attempt to discover this intangible value and how it informed the price placed on the bodies of the enslaved, the author draws from a trove of well-known sources like auction records or newspapers alongside less traditional documents in the form of poems and songs. This combination of sources results in more than 88,000 individual records that attempt to disassemble the system of slavery into its human parts.

In Chapter 1, Berry discusses the differences in estimation of procreating enslaved women from the Revolutionary era until emancipation through a combination of slave ads, abolitionist songs, and second-hand accounts of auctions. Beyond the physical attributes and work skills recorded in their sale, she finds that ‘breeding women’ were considered financially advantageous because they could procreate, thus commanding a higher price, but were also seen as a potential burden for owners unable to sustain additional enslaved offspring. To further support her findings, she presents abolitionist depictions of mothers separated from their children to demonstrate that there were other considerations that went into the calculations of slave owners, like the increased risk of escape to reunite with family or the effect that the trauma of separation could have on women’s productivity. These narratives, according to Berry, “clearly recognized the health and the humanity of the enslaved” and provided a glimpse of the ‘soul value’ of mothers by recording and substantiating instances in which they attempted to influence their fate. Evidence of concrete acts like escape attempts, and more internal strategies such as fantasizing about their children’s lives, individuate the different embodiments of motherhood under slavery while also supporting Berry’s contention, to the contrary of previous research, that child separations were in fact a common practice.

Building on the evidence of child separation, Berry explains in Chapter 2 how sex was rarely a metric for the prices set on children up until the age of ten, at which point, “enslavers could determine that their investment in human property was […] beginning to materialize. They had a better understanding of the strength and skills of growing children at age ten and began valuing them accordingly.” Hence, child separation was not a particularly significant transaction for enslavers, especially considering the high mortality rates and the uncertainty about enslaved children’s future value. Berry finds, however, that at age ten many enslaved children became aware of their status through sale or initiation into forced labor, and were attributed monetary value through their sale, appraisal, and insurance policies meant to protect the enslavers investment. As Berry explores in Chapter 3, the accumulation of traumas associated with these experiences along with the innate personalities of the enslaved make up “the spiritual value of their immortal selves” or their ‘soul value.’ Family and peers cultivated the recognition of this irremovable value during adolescence and young adulthood in the form of kinship and spirituality. This self-perception, according to the author, helped the enslaved fight against their commodification in different ways. In some cases, the enslaved were able to purchase themselves and family members, or they negotiated their own sales.

The last three chapters deal with a series of test cases in which Berry contrasts the prices in life of various members involved in different enslaved uprisings and their postmortem values or ‘ghost values.’ In the process, she finds that enslavers received reparations during slavery when their enslaved died or were killed. The loss and mourning of the families of the enslaved were also affected by the cadaver trade through which their loved ones could be exhumed without their knowledge or consent. Along with the varied archival materials that illustrate the weight of familial and romantic relationships between the enslaved in life and death, Berry’s strongest arguments come from findings about the use of Black bodies in this trade and how the practice further highlights the lingering shortcomings of economic histories of slavery and the slave trade. Her thorough analysis of the practices involved in the exhumation of bodies for medical research and training reveals the inextricable role of Black bodies in the development of modern medicine in the US. This study accentuates the glaring contradiction in dehumanizing the enslaved while at the same time using their bodies to further the study of human anatomy. To explain this almost inconceivable practice, Berry develops an analogy of the cadaver trade with the cycle of the cultivation of crops through the seasons in the year, demonstrating the level of complexity and forethought that went into the market of dead bodies as comparable to the agricultural industry. Her abstraction of the topic seems to recognize the impossibility of modern readers to imagine such a ghoulish practice and its relation with its modern counterparts in the trafficking of people and organs. This last connection of slavery’s contemporary relevance drives home the fact that spiritual reunification or peaceful rest in death was often beyond the realm of possibilities for the enslaved because their bodies continued to hold value in death. This new dimension, as Berry describes it, reveals as much about the commodification of Black bodies and about the impact of slavery beyond the physical lives of the enslaved. Nevertheless, by recovering ‘soul values’ she also proposes a way to humanize the record and thus dialogue, even if one-sided, with those we remember.