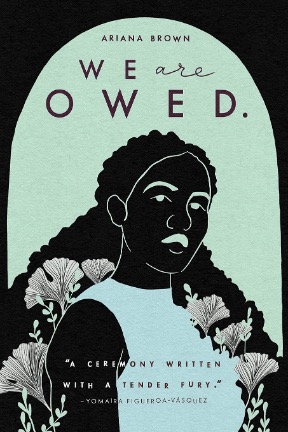

Ariana Brown

We Are Owed.

GRVLND, 2021

97 pages

$20.00

Reviewed by Silvana Scott

The first poem in Ariana Brown’s We are Owed, “At the End of the Borderlands,” begins with the betrayal of temporality as they write, “we need new origins countries are killing everyone I love.” After foregrounding the need for new origins as the primary demand of the text, Brown explains how they tried to heal and “slimmered rosemary & drank its tea” and also grew their “hair thick as plague.” When this proved not enough to “cure the colonizers curse”, they fed “each other our blackness grow full from offering.” After taking us on this narrative journey, Brown ends by denouncing the formative violence of nation-states and asks the recurring question, “who are you without your country?”

Beginning at the end, Brown cleverly subverts temporality in both the name and structure of the first poem, devoid of capitalization, punctuation, and sentence spacing. Alongside using structure, Brown sagaciously pens issues of colonialism, identity, refusal, healing, and liberation in their poetics to illustrate the immediacy of their material demands. Breaking away from normative poetic tradition, Brown organizes We are Owed. with a mixture of single-lined quotes from Black intellectuals, poems with varied spatial stanzas, pages with white space alongside a break symbol, definitions of phrases/words, and historical facts and notes with context.

Rethinking the space, lines, and visuals of the page, Brown denounces nationalism, settler colonialist violence, and state-sanctioned anti-blackness. Grounding their liberation away from the nation and illusory conceptions of latinidad, Brown places their poetics alongside a politics of refusal that looks towards a living otherwise, outside restrictive notions of cultural citizenship and nationality.

As part of a Black feminist lineage that uses refusal as a vehicle towards liberation, Brown refuses Western frameworks of national origins and relationality. Within this framework, Brown delegitimizes latinidad and its allegiances that stem from similar “la raza” thinking which fueled anti-black narratives of chicana/o studies. A page after the poem “Borderlands suite: Nightmares,” which details Brown’s childhood experiences with antiblackness and cisheterosexism within predominantly white and mestize populations, they write on a single blank page “I don’t want to use Anzaldúa’s language. I had a choice—to erase the words that erased me already or make a new one.” Refusing to accept the origin stories of Gloria Anzaldua’s Borderlands that erase Blackness, Brown instead focuses on creating new frameworks and doors that do not center narratives of nationalism or mestizaje.

In the second half of the text, Brown crosses temporal and spatial planes to discuss Texan Blackness and Mexican Blackness, which as Alan Pealez Lopez writes in the foreword, are poetic gestures that “serve as a form of betrayal to the ways in which Blackness is narrated both in the United States and in Mexico. This betrayal is rooted in love, Black love.” In reimagining new historical origins, Brown invokes Saidiya Hartman’s method of critical fabulation to address archival violence in the recording of two prominent Black historical figures: Esteban and Gaspar Yanga.

Brown first incorporates Esteban in “Don’t know nobody from Ellis Island,” where they weave in his presence after recounting an experience with a schoolmate named Guillermo, who was the “darkest Mexican she’d ever met.” Brown states that although they shared moments of unspoken relationality, she could not “lift her silent lip & smile.” Brown then writes that she did not see Esteban as the “prince of conquest… who survived the ocean twice” and whose “crossing the river” is where they “began.” The page after the poem ends is blank, besides a single statement that contextualizes Esteban as likely the first Black person in what is now known as Mexico, as an enslaved guide to the Spaniards in Galveston, mediating between them and Indigenous people.

Subsequently, Brown introduces Gaspar Yanga, who led one of the most successful slave rebellions in the Americas around 1570, in a series of poems and letters. Yanga later escaped with a group of followers and founded the first free settlements in the mountains of Veracruz, which grew to 550 inhabitants. Through a series of questions, songs and conversations, Brown engages Yanga in a range of topics, from his favorite fruit to pondering what he looked like, possibly having a gap between his teeth. Brown thus reimagines Yanga as a liberator with a wide range of being. Given the archival violence Brown encountered in their research on Yanga, she wrote to him and speculated on Yanga’s multiplicities in order to recover an undocumented Black past.

The final poem, “Inhale: the ceremony,” ends on a hopeful note about a politics of living otherwise, where Brown and their elders share moments of care as they bring rosemary and “fall into liquid.” They realize nothing “was ever lost… there was never this body or its wound, there was only water and the stories we passed through it.” Building off the confluences and fluidity of water, Brown provokes new ways of seeing origins and destinations. Thinking alongside Dionne Brand’s theorizing on the implications of maritime linkages in the Black diaspora, Brown calls for a reimagining of belonging that pushes forth a new reading of history to create a somewhere else, where kinship and relationality amongst Black people is not tethered to settler-colonial forms of subjugation.