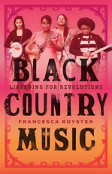

In Black Country Music, Francesca Royster seamlessly integrates her personal experiences of loving country music as a Black queer person with both the history of Black country and its recent incarnations. Royster begins with the familiar argument, that country music originated as a Black genre but was stolen and re-created by white people. She also describes her experiences venturing into country music venues that are implicitly white. Asking Black attendees about their feelings toward country music, Royster remarks that almost everyone demurred. She writes, “Maybe I was asking a fundamentally uncomfortable question, bringing to light an awkwardness that most of us, as we navigate white spaces, might try to ignore or suppress in order to enjoy ourselves.” Royster argues that country music spaces “can evoke and memorialize visceral memories of racialized violence; lynchings; the indignity of Jim Crow; gender surveillance and disciplining; and the continued experience of racial segregation in urban, suburban, and rural spaces in the North and South.” For Royster, Black people existing in these spaces is a form of queering. She focuses on the tradition of “country songs about being country” among black musicians, yet another way they are forced to prove they exist. Royster wants to move beyond the ever-present question of whether something is country to explore the Black, queer, and radical ways Black people make country music.

Royster extends the argument about the Black origins of country to the now when she says, “to put Black artists and fans at the center of this inquiry is to irrevocably shift country music as a genre. It forces us to remember, reengage and hopefully transform country music’s racial past. The music industry’s segregation of old time-music into race records and hillbilly music in the early twentieth century still informs the way the genre is policed.”

Royster then moves to case studies to show the ever-evolving ways in which Black country artists have always existed in spaces unwelcome to them. She begins with Tina Turner and her country roots, as well as her comparatively lesser-known country album. Royster shows that when she left the South, she didn’t leave her home. “Nutbush City Limits” is about complicating a home that was dangerous but made her, just like her cover of “Honky Tonk Woman” is a revision of “Black women’s sexual availability.” For Royster, these songs, and reclamations of the South, of the Honky Tonk, of the country, are a reclamation of a home and a past that belonged just as much to Tina Turner as it did to the white men that made the South dangerous for her to stay there.

Royster then explores Darius Rucker, who instead of remaining on the periphery of country music, has managed to navigate it as a country “bro,” using his Southerness and credentials as a Carolina Gamecock to get mainstream radio play. Royster argues that “Broness, is itself a transmogrification of Black cool and the projection of Black bodies as spaces of feeling, playfulness, manliness, and even unity.” Bro, like country music itself, was stolen from Black people and the shared intimacy that Broness connotes allows Rucker an in to primarily white spaces. That said, Royster is quick to point out that Rucker’s Black broness is in fact another performance, one that has garnered him success at the expense of a focus primarily on “racial uplift,” namely family and “traditional Christian values.” While a fan of many Black musicians, Rucker has also admitted to being a fan of Lynyrd Skynyrd. Only in the video for his cover of Old Crow Medicine Show’s “Wagon Wheel” does Darius Rucker portray himself as an outsider in the white spaces he plays and works in, years before he publicly admitted that “everything is not okay” in regard to race in the United States. By navigating the music industry as a Black country bro, Rucker has had to limit his political perspectives in ways that Tina Turner’s reclamations did not.

In Chapter Three, Royster focuses on Beyonce’s “Daddy Lessons” and what she calls the lie it asks us to believe, “that these performers are from completely different worlds.” But The Chicks and Beyonce are both from Texas, both from the South, both more regionally similar than their northern counterparts. Royster writes “African American music can be and always has been a part of country music’s sound and history.” There was an immediate backlash to Beyonce’s performance at the CMAs, to which Natalie Maines immediately responded that she would boycott them in the future. But as Royster shows, Country music has always made room for the white male outlaw, most prominently Johnny Cash. But Royster writes “maybe by being a Black woman, and a queer one at that, I am already an outlaw, whether or not I choose to be. There is a difference, of course, between the Outlaw that others dream up for me and my own resistance.” And even as The Chicks stood as allies with Beyonce, years after they were banned by country music charts and received death threats for opposing the Iraq War, Royster clarifies the ways that as white women, The Chicks can be Outlaws when Beyonce cannot—emphasizing their 2006 comeback album as well as their hit single “Goodbye Earl,” about murdering a domestic abuser. While “Daddy Lessons” is about rage, domestic violence, and family, as a Black woman, she cannot and will not murder the abuser. For Royster, it’s restorative justice rather than vengeance.

Royster goes on to discuss Valerie June, Rhiannon Giddens, and of course the ever controversial “Old Town Road,” which was denied by the country charts even as it hit all the notes of a country classic. These performers, and more, are part of a “Black Country Afrofuturism,” which the “Black Country Opry House” may be the pinnacle of. Royster calls on other black feminist scholars, like Adrienne Marie Brown and Alexis Pauline Gumbs, as she discusses an Afrofuturism that is already here, one that is in the words of Brown, an “emergent strategy.”

For Royster, Black people have always been essential to country music. Not just in the imagined past in which it was created, but in the present, where Tracy Chapman is charting for “Fast Car” and Beyonce is about to release an entire country album. In “Texas Hold Em’” Beyonce sings: “This ain’t Texas (woo), ain’t no hold ’em (hey) / So lay your cards down, down, down, down.” It might not be Texas, but for Royster, and for Beyonce, country music is for Black women, queer people and even bros, using it to reimagine a past, express rage, and create a vision for a new Black country future.