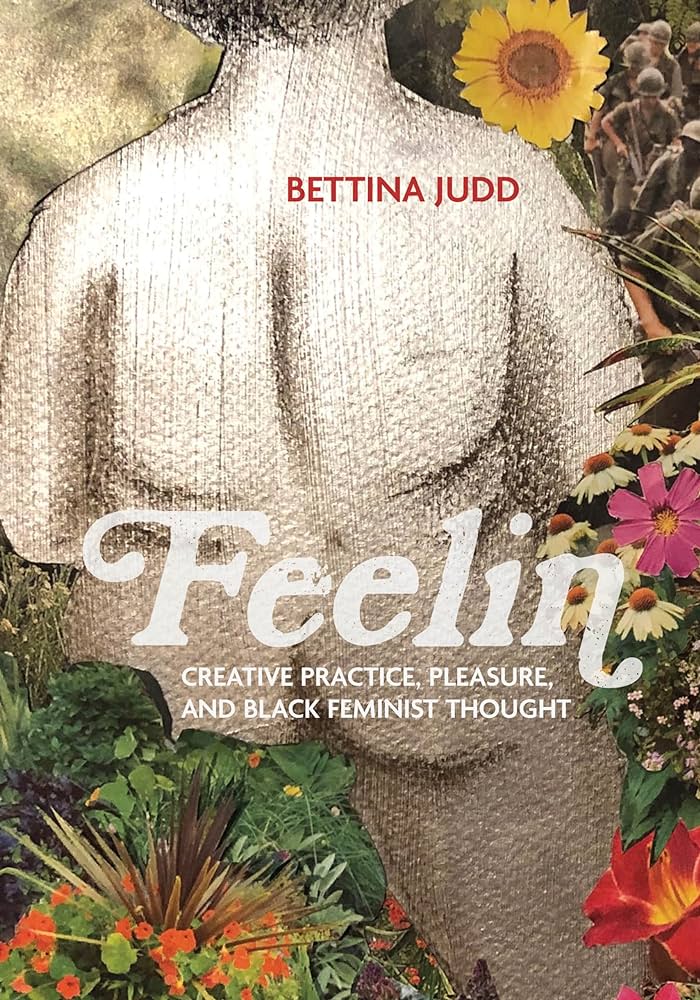

Bettina Judd

Feelin: Creative Practice, Pleasure, and Black Feminist Thought

Northwestern University Press, 2022

232 pages

$30.00

Reviewed by Miranda Allen

Feelin: Creative Practice, Pleasure, and Black Feminist Thought by Bettina Judd serves as a profound interrogation and celebration of how Black women’s creativity intersects with broader discourses on emotion, knowledge, identity, and self-awareness. Judd meticulously dismantles the artificial barriers between feeling and intellectual inquiry, instead arguing for a holistic understanding of Black women’s artistry that recognizes feelings, emotion, and sensation as central to the creative process and as a form of epistemological inquiry. Judd, an author, poet, and artist, does an exceptional job of allowing space for Black women’s lived experiences to speak for themselves, letting their authenticity, individuality, and uniqueness be emotionally expressed through various genres and mediums, including portraiture, poetry, historical literature, QR codes, charts, graphs, references to modern culture, music, and visual arts. Each of these mediums is chosen for its capacity to illuminate the complex interplay of emotion, creativity, and Black feminist thought.

This work leverages Black feminist thought to empower Black women, offering them a platform for authentic expression and challenging the entrenched norms and stereotypes that have historically constrained them. By doing so, it not only celebrates the resilience and achievements of Black women but also honestly acknowledges and represents their experiences of pain, shame, anger, and sadness. This interdisciplinary approach illuminates the complexity of Black women’s lives and underscores their vulnerability as a site of strength and transformation, aligning with the core principles of empowerment within Black feminist discourse and Black culture.

Judd’s introduction to the text conceptualizes what it means to feel, especially what it means to feel as Black women, an idea that has been overshadowed and overlooked in the mainstream context. She describes ‘feelin’ as a sacred knowledge that engages both emotion and sensation, acknowledging the influence of Audre Lorde’s work on erotica within every Black woman and their artistry. In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, (1984), Lorde describes the erotic as a powerful, deeply feminine, and spiritual force within us, linked to feelings we might not express or even acknowledge. Systems of oppression aim to weaken the oppressed by targeting these internal power sources, including the erotic, especially for women. This involves diminishing the erotic’s role as a valuable source of strength and insight in our lives, thereby maintaining control and preventing change. In the powerful synthesis of Lorde’s insights with her own, Judd reclaims the erotic as a site of empowerment within Black women’s creative practice and calls for re-evaluating how society perceives and values the depths of their feelings. This reclamation is presented as an act of defiance and a necessary step toward the liberation of Black women’s full expression and existence.

Following the introduction, Judd delves into the first chapter, focusing on grief—a theme she explores through the prism of Black studies and personal narrative. Music is presented not just as a backdrop to these experiences but as a language capable of conveying the complexity of Black women’s joy, pain, resilience, and resistance. Judd harnesses the emotive power of the blues and other forms of Black music, known for their raw expression of the human condition, to paint a vivid portrait of mourning that is both intimate and universally resonant. Judd’s prose sings with the same richness as the music she describes, drawing parallels between the lyrical sorrow of blues and the profound loss felt within the Black community. The riff, a recurring motif in blues music, becomes a metaphor for the cyclical nature of grief, with its circular patterns of ascension and descent echoing the ebb and flow of emotional healing.

Visual and musical arts emerge as a canvas upon which the depth of Black women’s inner lives is painted, revealing the strokes of their struggles and triumphs. Chapter 3 explores the power of voice and song as Judd states, “If I could write this chapter right, it would sing for you.” Judd discusses the concept of ecstatic vocal practice, which merges elements of the sacred and the sexual. She describes singing as a “tool that some Black women vocalists have used for unlocking their own desires and engaging in this intimate touch.” This practice is exemplified through the works of artists like Avery Sunshine and Aretha Franklin. By referencing these artists, Judd illustrates how Black music often intertwines sexuality, vulnerability, and spirituality, capturing the complex emotions associated with erotic desire and divine presence. This approach highlights the depth and breadth of Black women’s experiences as reflected in their musical and artistic expressions, emphasizing the dual themes of sexuality and spirituality prevalent in their lives and work.

Chapter 4 stands as a critical reflection on the intersection of motherhood with the socio-political dynamics of race and gender, challenging the reader to confront uncomfortable truths while simultaneously offering a vision of hope for transformative understanding and change. Judd confronts the stigmatization of Black motherhood, critiquing the stereotypical images—Jezebel, Mammy, and Matriarch—that have historically framed Black women. She argues these stereotypes not only misrepresent but also further expose Black mothers to societal shaming and violence. Her analysis reveals how these controlling images devalue Black women’s bodies and experiences, perpetuating a cycle of vulnerability and disrespect. Judd’s examination calls for reevaluating the narratives surrounding Black motherhood, advocating for recognition of Black mothers’ autonomy and humanity. This chapter is a powerful appeal for a shift in societal perception, urging a move toward genuine respect and support for Black mothers.

In the final chapter, Judd zeroes in on the topic of Black women’s anger, examining its portrayal and significance in creative expression. She challenges the pervasive stereotype of the ‘angry Black woman,’ advocating for a deeper understanding of this emotion. Judd argues that anger, often depicted as an unwanted avatar, is a legitimate and revealing response to the intersecting experiences of racism, sexism, and misogyny. Her analysis suggests that by acknowledging and interpreting Black women’s anger through their art and speech, we can gain a clearer insight into Black feminist thought and the production of knowledge from these lived experiences.

Judd’s voice is both a guide and a participant in the narrative, creating a bridge between the reader and the subject matter rooted in empathy and understanding. The book does not shy away from the difficult conversations about the stereotypes and systemic barriers that have historically silenced or marginalized Black women’s creative output. Instead, it faces them head-on, deconstructing these narratives and reconstructing a world where Black women’s artistic contributions are celebrated for their inherent worth and capacity to challenge and redefine the boundaries of Black feminist thought. Feelin is not just a scholarly work; it is a celebration, a recognition, and an affirmation of the transformative power of Black women’s creative practice. It is a testament to the undying spirit of Black womanhood and its ability to feel deeply and express profoundly. Judd’s work significantly enriches the conversation around the nuances of Black feminist perspectives, particularly in how they intersect with emotional and affective experiences. It serves as a guiding light for those who seek to comprehend the essential function of emotion in creating knowledge and self-expression.